Language is powerful.

We choose words carefully in our written works because we understand their impact. They carry a message from one mind to another. They shape ideas. They can change lives.

But writers often use language carelessly when it comes to the business side of being an author, and it shows that many still don’t understand copyright, and how rights licensing can impact your publishing choices, as well as your financial future.

I’ve run across several examples of this recently in discussion with author friends and also online, so I thought it was time for a refresh on intellectual property (IP) — and how important it is to define terms as we move toward Web 3 and a new iteration of what ‘digital’ even means.

Intellectual property rights are the building blocks of an author career.

You have to understand IP and rights licensing in order to make a living as an author for the long-term, whether you work with an agent or you’re entirely independent.

It might take a little getting used to, but once the penny drops around intellectual property, your language will change and you will have the power to shape your author career in a much more effective — and profitable — way.

Note: I am not a lawyer/attorney and this article is not legal or financial advice.

This article is based on learning about intellectual property from books, courses, and my personal experience publishing independently since 2008. It is a huge topic, so I can only scratch the surface and hopefully, give you something to think about and resources to take your knowledge further.

In this article, I cover:

- An overview of intellectual property rights related to written work

- Original written work = Intellectual property asset

- Print, Ebook, Audio

- Other rights licensing opportunities

- What rights have you licensed? Are you leaving money on the table? Plus, the issues with licensing “digital” rights as we move toward Web 3.

- More resources — books, courses, podcast interviews

An overview of intellectual property rights related to written work

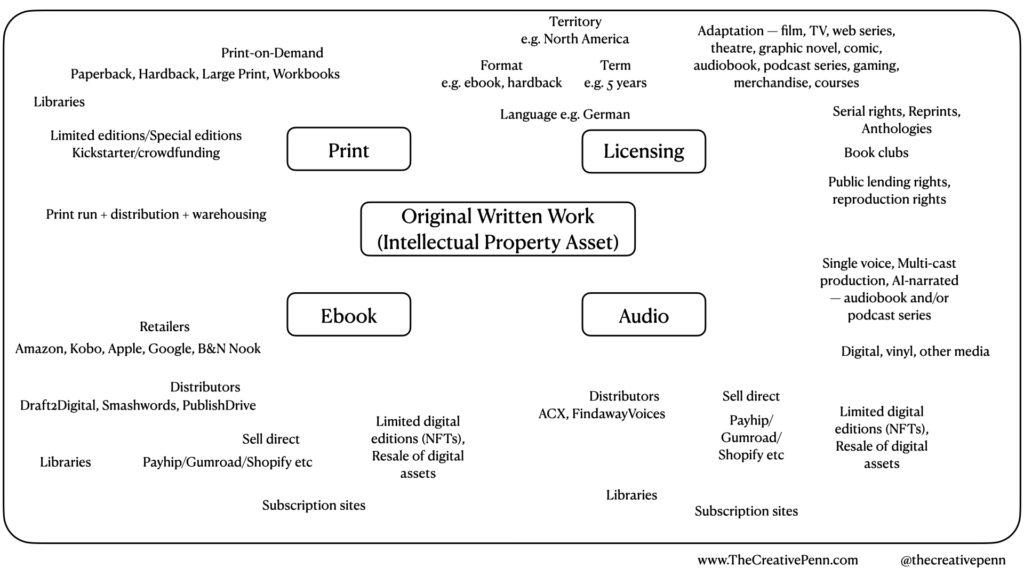

The following diagram contains some of the ways you can license your intellectual property. Click here for a larger image.

This is a simplistic representation to give you some idea of the depth and breadth of the possibilities of rights licensing, but don’t think of rights as a list or a static diagram.

Think of rights as a matrix where you can mix and match in different ways.

For example, you can license ebook rights in German to European countries for a 10-year term. Or single voice digital audiobook rights in English for UK Commonwealth territories for 7 years.

Each original written work is a new opportunity to license rights, so as you create more stories, essays, books, novellas, and all the other possible things, you can start all over again with licensing each one (unless you have already licensed a specific universe or characters). Your IP ecosystem multiplies with each work created.

You can slice and dice your rights in lots of different ways, which Dean Wesley Smith describes as a “magic pie” in his book, The Magic Bakery (recommended!). It’s magic because you can carve each one into unlimited numbers of slices and they also return to you over time as licensing terms end. Then you can license them all over again.

You can license the work to others by signing a contract for specific rights, or you can exercise rights yourself using many of the technologies available now. Some call the latter “self-publishing,” but the world of rights licensing by independent creators is far bigger than such a reductive term these days, which is why many of us use ‘indie author,’ or ‘independent author,’ in the same way that indie musicians or indie filmmakers embrace the term.

Many authors combine rights licensing, contracting with publishers for some rights, and then managing others themselves, for example, independently publishing English language ebooks, while licensing foreign language editions, which I do for some of my books.

I absolutely encourage you to license your rights and work with partners to expand the opportunities of your intellectual property. But license selectively, as the Alliance of Independent Authors explains in their Ultimate Guide to Rights Licensing.

Let’s get into the details of the diagram.

Original Written Work = Intellectual Property Asset

You are writing a book (or a story, or an essay, or a poem, or other written work) but you are also creating an intellectual property asset. Language is important, remember! It can change your perspective on the value of your work.

Copyright in that work lasts 50-70 years after the death of the author (depending on your territory). See The Copyright Handbook for more detail and I’ve included other resources at the end of the article.

You license rights to the work. You do not ‘sell’ a written work — unless you are writing for hire, in which case you are actually selling your time to create an intellectual property asset for someone else e.g. freelance writers, ghostwriters, and any contract where you sign the copyright over to the person who pays you.

This article is for writers who own, control, and license their intellectual property.

Note: There is no copyright in an idea, only in the original expression of the idea. I’ve also used written work here since we are authors first, but it applies to other media e.g. audio, images etc.

There are many different formats of print books and ways to produce them.

Independent authors mostly use KDP Print for Amazon and Ingram Spark for wide distribution, meaning your book can be ordered by bookstores, libraries, universities and appear in Print On Demand storefronts across the world, e.g. bookshop.org and others.

Print-on-demand options have revolutionized print publishing because you don’t have to pay upfront for printing costs, warehousing or shipping, etc. You upload files of your book (cover and interior) and when a customer orders, a copy is printed and sent directly to them. The customer pays for the printing and shipping and you receive the profit margin that you determine on upload.

There are many variations and sizes of books, paper type, color/B&W etc. I publish paperback, hardback, and large print editions as well as companion workbooks with print-on-demand. [Links to all my books here.]

The primary method used by traditional publishing is to do a print run (e.g. 10,000 books) and then use distribution services, warehousing, shipping and physical stores, libraries etc to get the books into the hands of readers. The pandemic and the increasing move to online shopping have encouraged more traditional publishers to use print-on-demand in addition to, or instead of, print runs.

Some successful independent authors use print runs and distribution in the same way as traditional publishers. For example, British crime writer LJ Ross with Dark Skies Publishing.

Others use small print runs as special editions through Kickstarter and other crowdfunding platforms. Examples include Brandon Sanderson’s $6.7m Kickstarter for the special edition of The Way of Kings, as well as more modest projects like Orna Ross’s Secret Rose, a gold-embossed hardback.

You can also license print editions and not include ebook, audio, or other digital formats, for example, as Mark Dawson has done with Welbeck Publishing Group.

Ebook

There are different ebook formats, for example, ePub, mobi, PDF.

You can produce them yourself, for example, with Vellum or Atticus, or you can pay a professional for formatting. Or you can license your rights to a publisher.

There are different retailers where you can sell ebooks and different apps to read on. For example, I upload my ebooks for sale direct on Amazon KDP, Kobo Writing Life, and Apple Books.

There are different distributors who will distribute your ebooks to many other retailers and libraries, as well as subscription sites. For example, I use Draft2Digital to send my ebook to Nook, as well as Overdrive for libraries, and places like Scribd for ebook subscription.

If you own your digital rights, and have not signed any exclusive clauses, you can sell your ebooks direct to customers and they can read them on whatever app they prefer. I use Payhip with Bookfunnel for seamless delivery to mobile and e-reader devices at Payhip.com/thecreativepenn (If you want to set this up, see my tutorial on selling direct here).

An emerging opportunity is the use of NFTs for digital limited editions, which can also be resold using smart contracts on blockchain. This model is being adopted by independent visual artists and musicians much faster than in the publishing industry, but will be a new source of income in the next decade.

There will also be many more applications with blockchain and Web 3, and potentially many more digital formats. It’s early days now, but it is coming… Just think how undervalued ebook rights were in 2008. [More on futurist topics including NFTs here.]

Audio

There are different audio formats, for example, MP3, MP4, wav, for digital audio. It can also be produced in physical format, e.g. tape, CD, vinyl, and there may be other media in the future.

There are different types of audio product, for example, single voice audiobook, multi-cast production/audio drama, AI-narrated audiobook, or podcast series.

You can produce these yourself, either by self-narration (which I do for my non-fiction and short stories), or by hiring a professional narrator (which I do for fiction and used to do for non-fiction), or by using AI-narration through a production company, or by licensing your rights to a publisher.

There are different retailers where you can sell audiobooks to customers, or they can borrow as part of subscription or library models. Most indie authors use ACX for Audible and FindawayVoices for wide distribution (to over 40 retailers, library and subscription services).

You can sell your audiobooks direct to customers and they can read them on whatever app they prefer. I use Payhip with Bookfunnel for seamless delivery to mobile devices at Payhip.com/thecreativepenn. (If you want to set this up, see my tutorial on selling direct here).

Limited edition audio is another possibility. For example, the vinyl format has seen a resurgence, and NFTs for audiobooks and other audio products are an emerging digital option.

There are also many different income models around audiobooks and podcasts, which I cover extensively in Audio for Authors: Audiobooks, Podcasting, and Voice Technologies, also available in audio format narrated by me.

Other rights licensing opportunities

Rights licensing is usually based around:

- Format e.g. ebook, paperback, audiobook defined to specific types of each and royalty levels for sale

- Territory e.g. North America, UK Commonwealth, World

- Language e.g. German

- Term e.g. 7 years

- Specific work (sometimes more than one, and sometimes with an option for other work in the world or under the same author name)

There are also many options for subsidiary rights licensing. Some include:

- Adaptations — film, TV, web series, plays/theatre, graphic novel/comic, podcast series, gaming, merchandise, online courses

- Serial rights, reprints, anthologies

- Book clubs

- Public lending rights, reproduction rights (for example, ALCS in the UK collects these on behalf of authors for library borrowing and photocopies etc.)

Selective rights licensing means you choose to limit the license to whatever the publisher is capable (and likely) of producing. It is very unlikely that a publisher will be able to use all rights in all formats in all territories in all languages.

For example, I license World French electronic, audio, and print for specific non-fiction titles for five years with a first option to renew.

If you license selectively, you can also independently publish in other formats, territories, and languages. For example, I have now sold ebooks in 168 countries — and that’s just through Kobo.

I am always interested in discussing selective rights licensing for my books, but I won’t sign a contract for “World territories, all languages, all formats existing now and to be created, for the term of copyright.”

If you sign a contract with this clause (or something similar), make sure you get a lot of money as an advance!

What rights have you licensed? Are you leaving money on the table?

If you have any form of written content available for someone else to read or purchase or listen to, then you have signed a contract that will include some kind of license.

If you are traditionally published and someone has paid you for your rights, check your contract to see what you have agreed to.

Many traditionally published authors I talk to will say they don’t know what rights they have signed, which shows they don’t understand how copyright works. If you don’t know what you’ve signed, then you don’t know what else you can do with your body of work. If that’s you, go check your contracts. You might be leaving money on the table.

If you’re an indie author, you sign a contract when you accept the terms and conditions of whichever service you use to publish. So read the Ts&Cs, download a copy, and keep them somewhere as evidence of what you have ‘signed.’

Many of the sites have a non-exclusive contract for a specific format, e.g. Kobo has a non-exclusive right to your ebooks so you can always publish them elsewhere.

Some sites have exclusive options. For example, if you opt into KDP Select and make your ebooks available on Kindle Unlimited, that is a 90-day exclusive contract for your ebook, so you can’t use any other publishing or distribution service, or sell direct, for the term you enroll. That doesn’t stop you from licensing your audio or print rights, it just limits your ebook options. [More on exclusivity vs going wide here.]

Some sites have terms and conditions that are being questioned by authors and author organizations, for example, check out #audiblegate and the investigation into Audible’s contracts.

Understand the implications of what you are signing. Have all terms been defined?

Any contract should contain definitions of terms because those definitions matter when it comes to what you have actually licensed.

There was a time when publishing contracts did not include digital publishing rights, or clauses around ebooks, print-on-demand, and digital audio. But in the early 2000s, it became clear that the internet and e-commerce were taking off, so publishers sent round addendums to contracts so that authors would sign those rights over, too.

In February 2008, Kate Pullinger wrote in The Guardian, “My agent recently received a sheaf of contracts that are intended to secure digital publishing rights for my backlist, titles that were previously published in print.”

The article encourages authors to value their rights, ending with, “At the end of the day, the writer herself is a more valuable brand than the publishing house and it’s time for writers to wake up to this fact: why should we sign contracts giving us a paltry 15% royalty in an industry where actual costs are being massively reduced overnight? Why aren’t writers jumping up and down over this?”

Most writers did not jump up and down and most writers signed that addendum.

But some didn’t.

JK Rowling kept her digital rights and founded Pottermore in 2012 to publish the ebook and audiobook editions of Harry Potter and, of course, there have been many other licensing deals struck since then. Pottermore is now a multi-billion dollar company [Financial Times.] Of course, we won’t all have that kind of success, but opportunity springs from understanding copyright, and we can all learn from that!

The issue now is one of definition because we are moving into a new era of digital, one that goes beyond the existing terminology.

Some call it Web 3 and it encompasses blockchain, AI, VR, AR, and other technologies with potential formats that do not even exist yet.

But language is powerful and many publishing contract terms are not clearly defined. For example, ‘digital,’ ‘ebook,’ and ‘special edition’ need to be defined more carefully in contracts as new formats emerge.

NFTs are unique digital assets, essentially digital limited editions in the terminology of publishing. They are minted on specific blockchains and executed with smart contracts, which might include resale royalties. Where are these covered in current publishing contracts? Do NFTs come under ‘ebook’ or ‘limited editions’? Who gets the income from resale? Where is that defined? [More on blockchain, NFTs, and other creative futurist topics here.]

This issue might only be emerging now, but consider how many authors signed away ‘digital rights’ in the early days of the internet without understanding the potential long-term value.

It’s 2008 all over again for blockchain applications of rights licensing, which will become incredibly valuable in the next 10-15 years.

Empower yourself.

As we move into the next reinvention of the digital world, there will be more opportunity than ever — but only for those who own and control their intellectual property and understand rights licensing.

If you spend a little time learning about intellectual property, licensing rights, and contract terms, you could expand your income streams for the long term — and that’s exciting!

Books, Courses, Articles, and Podcast Interviews

- The Magic Bakery: Copyright in the Modern World of Fiction Publishing — Dean Wesley Smith

- Closing the Deal… On Your Terms: Agents, Contracts, and Other Considerations — Kristine Kathryn Rusch

- Advanced Lecture on Copyright — with Dean Wesley Smith

- The Copyright Handbook: What Every Writer Needs To Know — Stephen Fishman

- The Ultimate Guide to Rights Licensing for Indie Authors — Alliance of Independent Authors

- Selling Rights — Lynette Owen (This book is aimed at UK agents and publishing companies so it’s an interesting insight into the other side of the equation.)

- The Importance of Self-Editing and Why You Need To Read Your Publishing Contracts with Ruth Ware

- The Key To Long Term Success as a Writer with Kevin J Anderson

- Value Your Books for the Long Term with David Farland

- Empowering Authors Around Copyright with Rebecca Giblin

- Creative Law Center blog with Kathryn Goldman

- Articles and podcast interviews on Web 3, AI, blockchain and the future of creativity

I hope you found this article useful and thought-provoking. You’re welcome to leave a question or comment and I will do my best to answer any queries or point you to other resources.

[Note. I am not a lawyer/attorney, and this is not legal or financial advice. It is just my opinion based on books, courses, and experience publishing my own books and licensing rights since 2008.]

The post You Are A Writer. You Create And License Intellectual Property Assets. first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn