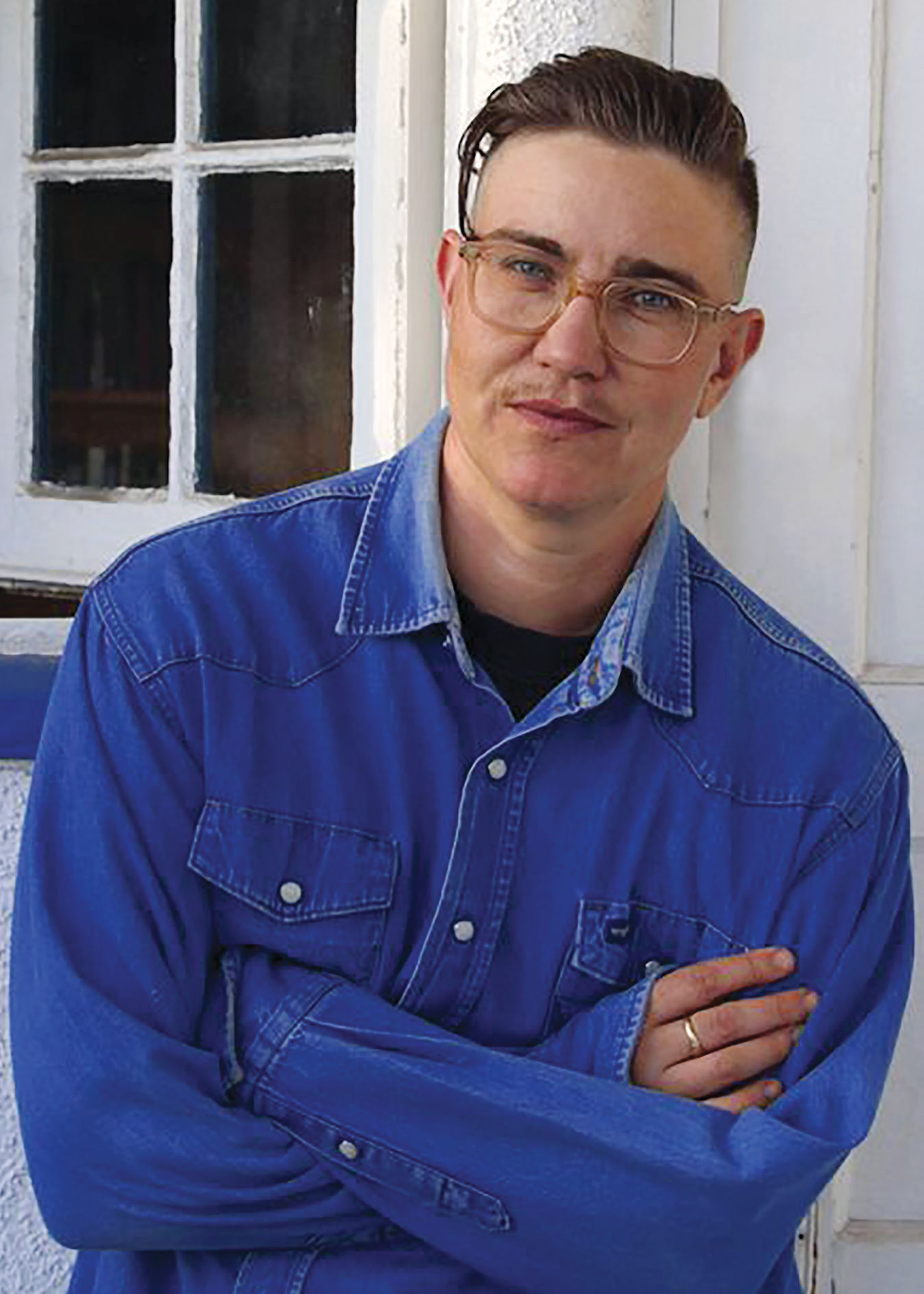

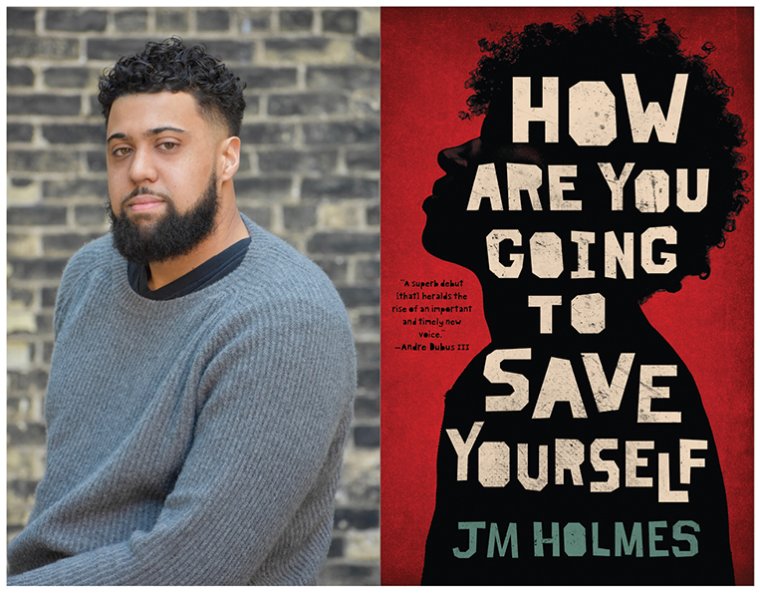

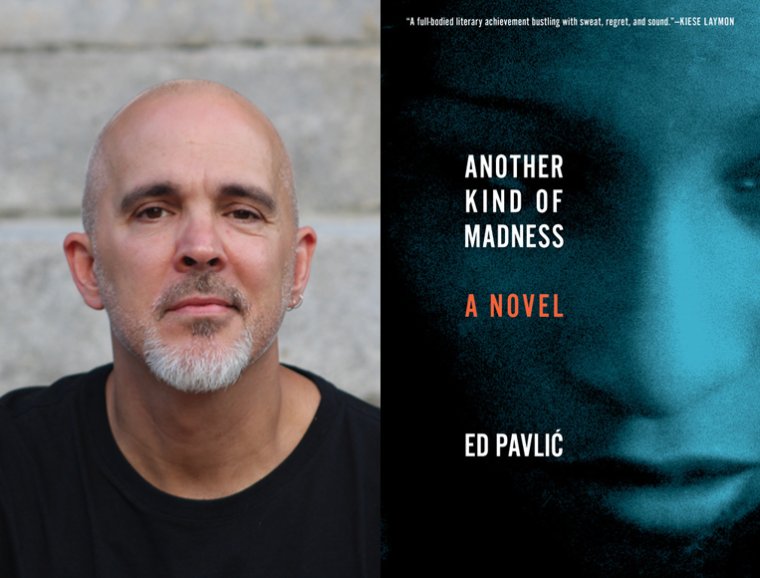

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Ed Pavlić, whose novel Another Kind of Madness is out today from Milkweed Editions. The epic story of Ndiya Grayson, a young professional with a high-end job in a Chicago law-office who meets Shame Luther, a no-nonsense construction worker who plays jazz piano at night, Another Kind of Madness moves from Chicago’s South Side to the coast of Kenya as the pair navigate their pasts as well as their uncertain future. Of the novel Jeffrey Renard Allen writes, “In these pages, Black music sounds and surrounds experience like a mysterious house people long to live in but can’t find, a quest where they find themselves ever more deeply involved.” Widely published as a poet and scholar, Ed Pavlić is the author of the collection Visiting Hours at the Color Line, winner of the 2013 National Poetry Series, as well as ‘Who Can Afford to Improvise?’: James Baldwin and Black Music, the Lyric and the Listeners and Crossroads Modernism: Descent and Emergence in African American Literary Culture.

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’ve always written in and around the gifts and demands of family, parenting, etc. I have no real literary credits that pre-date my life as a father and husband. In fact, often I’ve worked while pretty confused about which aspects of all of that were “gifts” and which were “demands,” demanding gifts in any case. I’ve also written in and around the work as a professor and administrator in universities. For many years I found I could compose and revise poems in the momentary midst of all of that overlapping life and labor. Most likely poems were the way I survived those overloads, kept track of enough of the mind and body, all those minds and bodies, so that I didn’t go permanently off the rails. So I could at least find my way back to the tracks when wrecks and crack-ups did—and they did, of course—occur.

Maybe writing was and is a way to address the displacements of an upwardly mobile, cross-racially identified, working-class man amid waves and undertows in an intensely segregated, hyper-racialized, and hierarchical bureaucratic world. Or maybe, for a working class consciousness like mine, writing is just another wave of displacement? Most likely it’s both. I guess we could file most of these thoughts under the “where” I write part of the question.

2. You write both poetry and prose; does your process differ for each form?

Essays and other longer works weren’t as immediately about or out of that tumble of pleasure and trouble, of placement, displacement and replacement, of the startling novelty and bone-bending drudgery of, say, early parenthood, or of showing up to work in the unbelievably bourgeois and indelibly white halls of academia. At least that work wasn’t doused in the texture of my tumbles and pleasures in the same way. So, I’ve written what might pass as prose, and lots of it, in times when I can work for extended periods, on days—at times weeks or even months—when I don’t have to totally leave that space tomorrow, where I didn’t arrive fresh to it today. So, if I’ve got four days “off” from the rest of the work-world, I can work away at what’s called prose on the middle days.

3. How long did it take you to write Another Kind of Madness?

I wrote Another Kind of Madness in a way unlike anything else I’d ever written, or done. I worked on the novel only in spaces where I had at least a month in which I could be with the work unencumbered by the demands of life and employment. I began it in the summer of 2009 when the kids were old enough (and my in-laws young enough) that they could be with the grandparents in Maryland for six weeks during the summer. Stacey went to work and I turned the front porch in Georgia into a writing retreat. Working “at home” in this way was something I’d almost never done. After that summer, I worked on the book in similar breaks of a month or two, but never again at home. Instead, I worked in rented, borrowed, or gifted spaces in Montreal, at the MacDowell Colony (twice), in Istanbul, in Mombasa, and in Lamu Town on the coast of Kenya, in France, and in the West Farms section of the Bronx, a few blocks south of the Bronx Zoo one summer.

During these strange times I floated by myself in mostly urban, unfamiliar spaces, writing a few hours a day and then spending the rest of the days and nights accompanied by the story on walks, at meals, in dreams, on errands, in reading books I found in those places, etc. I found that the story wouldn’t reveal itself amid the tumble of my life, would only appear when I could really sit, walk, and sleep with it, where it could accrue its reality in a textured and present—but also most often in a peripheral and angular—region of my attention. The pressure of my daily worlds seemed to obliterate that nimble angularity, but my comings and goings in those unfamiliar urban spaces allowed this story to happen. I remember showing up after eight months away from the book, opening a blank, unlined (yes, unlined: “free your lines, the mind will follow”) notebook and waiting for Shame, Ndiya, Junior, Colleen and them to let me know what had been happening since we last saw each other and, in return, I tried to be as honest with them as I could be about what had been happening with me. It was always as if, unknowingly, we had, in fictional-fact, been at some of the same parties.

4. What has been the most surprising thing about the publication process?

That it takes a village.

And, with this book, a novel, with this novel, how dense the space between the lines is with things (references, inferences) that I don’t remember creating. So many things that never appeared to me until the ARC came between the covers. At that point I could see it as a thing outside my body, and I noticed all kinds of new things there. That was a surprise, for sure; the book was a stranger to me in a way I didn’t expect. The poems aren’t that way, essays either. I’ve left copies of the ARC around the house and, when I walk past them, I’ll pick up the book and turn to a random page and begin reading at the first new paragraph, halfway trying to catch it actively changing, as if I can catch it coming up with something else it hadn’t told me about.

5. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I’d love to see more recognition in and between writers of what happens in and around Black music, where singers are singing in an organic kind of tandem with tradition, in which songs bristle with depths and complexities quite beyond the capacities of any particular singer. And audiences seem to roll with that, we almost insist upon it. I don’t think we insist upon or even at times allow a similar kind of dimensionality with our sense of writers and writing. It happens in contemporary writing, of course; but I think it’s less obvious to readers than that similar dynamic is to listeners. Maybe readers even refuse it. Maybe I’m saying that I’d love the community of contemporary writers to read each other with the freedom and rigor (vigor) we bring to hearing the music we love the most. I struggle to do this myself. Maybe singers need to listen to each other with the freedom they read with? I don’t know.

6. What are you reading right now?

I’m always reading multiple books, always accompanied by music in the background and foreground. Right now I’m reading Singing in a Strange Land, Nick Salvatore’s biography of C. L. Franklin (Aretha’s father); David Ritz’s Respect: The Life of Aretha Franklin; Eve Dunbar’s Black Regions of the Imagination; and I just finished rereading Danielle McGuire’s At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance. My rereading of Jesmyn Ward’s Men We Reaped begins today. Meanwhile, I’ve been listening to five discs in the changer (Aretha’s double disc set, Amazing Grace: The Complete Recordings, Marvin’s What’s Going On, and Coltrane’s Both Directions at Once: The Lost Album) on endless loop for weeks. I’m working my way into writing something about the recently released film, Amazing Grace, that was made while Aretha was recording the album with James Cleveland and his choir in Los Angeles in January 1972. Aretha performs with absolutely stunning, epic power. It’s incredible. Easily the most powerful thing I saw / heard / felt on film in 2018.

I listen to and stream contemporary music mostly in the car. The latest song I’ve been repeating all around town is Summer Walker’s newly released “Riot,” from her EP Clear. So good. It’s like Sade’s “Is It a Crime” for the 21st century.

7. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Well, so many of course. The word “author” almost means “deserves wider recognition.” Though not always. I’d say Christopher Gilbert, his Turning Into Dwelling. Also the second half of Adrienne Rich’s career, especially: Your Native Land, Your Life (1986), Time’s Power (1989), An Atlas of the Difficult World (1991), Dark Fields of the Republic (1995) and Midnight Salvage (1999). Adrienne Rich is obviously a widely recognized writer, but the woman who wrote these books—meaning those poems—is mostly unknown. Also I’d say the Ghanaian writer Kojo Laing, his masterpiece Search Sweet Country.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Racial terror. A feeling that—like how the finest silt settles on every plane in a space and then somehow constitutes an immobilizing weight—one is operating in a prison to which we’ve been trained to accommodate (meaning obliterate) ourselves. But, you can’t really write—at least not very well—about that, or at least I can’t. I need to catch it when it flashes into view, before it becomes something it’s not, which is usually all we know. The need to arrest that unknowing, at times excruciating yet still unfeeling, state that takes our steps elsewhere to where we’re walking.

So all of that and, I think, a kind of impatience that masquerades as procrastination.

9. What’s one thing you hope to accomplish that you haven’t yet?

I need to write my mother a letter.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

In 1976, when James Baldwin told a writer’s group in the women’s prison at Riker’s Island: “One can change any situation, even though it may seem impossible. But it must happen inside you first. Only you know what you want. The first step is very, very lonely. But later you will find the people you need, who need you, who will be supportive.”

Over the last twenty-something years, I’ve found that to be absolutely true. I come back to that statement all the time.

Or maybe the best is, in 1970, when Baldwin told John Hall: “Nothing belongs to you…and you do what you can with the hand life dealt you.” I think if we can proceed with that in mind we can figure a few profiles of the ways, we do, in fact, belong to each other. I’m not talking about holding hands at sunset, I’m talking about a sense of mutual consequence that moves with the power (redemptive) of accuracy.