How can we recognize self-doubt and create alongside it as part of the author journey? How can we write with confidence and double down on what we love the most? William Kenower talks about these aspects and more.

In the intro, planning for 2022 [Ask ALLi]; Your publishing options [6 Figure Authors]; Need an audiobook narrator? Use the Findaway Marketplace; The Successful Author Mindset.

Today’s podcast sponsor is Findaway Voices, which gives you access to the world’s largest network of audiobook sellers and everything you need to create and sell professional audiobooks. Take back your freedom. Choose your price, choose how you sell, choose how you distribute audio. Check it out at FindawayVoices.com.

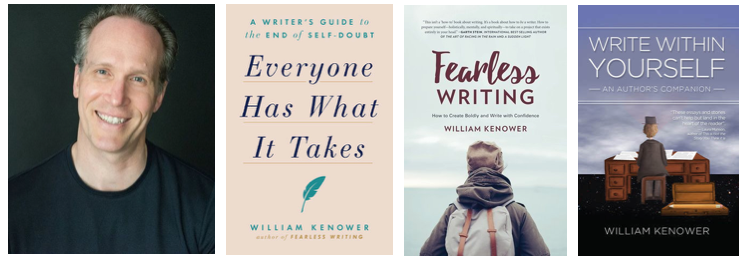

William Kenower is the author of nonfiction books on writing, the editor-in-chief of ‘Author Magazine’ and the host of the Author2Author podcast. His latest book is Everyone Has What it Takes: A Writer’s Guide to the End of Self-Doubt.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- A winding route to writing and publishing

- Validation — and the need to find it within ourselves

- The different ways that writers experience self-doubt

- Learning to recognize self-doubt and create, anyway

- When is self-doubt justified, and what can you do about it?

- Does everyone have what it takes to be a writer?

- Commonalities among successful writers

You can find William Kenower at WilliamKenower.com and on Twitter @wdbk

Transcript of Interview with William Kenower

Joanna: William Kenower is the author of nonfiction books on writing, the editor-in-chief of ‘Author Magazine’ and the host of the ‘Author2Author’ podcast. His latest book is Everyone Has What it Takes: A Writer’s Guide to the End of Self-Doubt. Welcome to the show, Bill.

William: Thank you, Joanna. It’s good to be here.

Joanna: It’s great to have you on the show.

Tell us a little bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing.

William: Writing, I got into very young. I knew the arts were really the only path I was interested in. And though I dabbled in theater pretty seriously in my early to mid-20s and I went to Hollywood briefly with the idea of being a screenwriter. Prose was really where I was most comfortable and writing and prose was where I was most comfortable.

And so that was really always the plan for me. I knew people did want to be things besides artists, but it was hard for me to understand why. It just seemed like the best possible way to earn a living if you could do that. I was singularly set on that.

As far as publishing though, when I thought about being a writer, publishing was simply what other people did; it was like a giant oven run by agents and editors, into which I inserted a manuscript and out popped mysteriously, a fully baked book.

I didn’t see myself as getting into publishing. Although interestingly, Joanna… Actually, I was thinking about this beforehand in a way because I know this podcast, a lot of your listeners are indie published.

The theater I did when I was in my early 20s, my brother and I put on a sketch comedy show and it came about because I was doing poetry readings that were very theatrical, and my brother and I said, ‘Let’s do a show.’ And part of the reason we did it was I was writing stories and poems and sending them off to magazines and was not enjoying.

Of course, I just didn’t like the rejection, but also, I was frustrated with the gatekeeper set up, what I thought of as the gatekeeper. I thought, ‘Well, why does this one person determine who gets to read my stuff?‘ It seemed weird.

When I found myself standing on a stage because it was sort of like I was going to just art spaces and areas where anybody could just get up and do stuff, sort of like open mic type situations. I thought, ‘Well, why not just find some place where I put the thing up and anybody who wants come can come and they can decide if they like it or not.’

So it was essentially self-publishing theater. I wrote it, my brother and I directed it. We found the venue, we put up the posters and people started coming. So it was independent. It made sense to me at the time.

Joanna: I would also argue you’re a podcaster and this is publication. We create a product with our voices. We hit publish and no one else gets in the way, right?

How long have you been podcasting now?

William: I’ve been podcasting for 10 years. And even before that, this is what I was going to say, is I was writing and submitting. And remember when I started writing fiction, this was in the early ’90s. Self-publishing was such a hard sell because it didn’t have the digital world, right?

Joanna: And there was a big stigma back then.

William: And it was a stigma around it. I just had zero interest in it. So I was wanting to publish traditionally and not having much luck.

When I started ‘Author Magazine,’ I was publishing an essay every day. I would write one a day. But I was the editor-in-chief. I was the gatekeeper. So I was essentially self…not essentially. I was self-publishing. It’s just that I had an established audience.

That was really where I found my voice. One of the challenges that people have around publishing, and it’s a pretty… It’s not even disguised, the idea of getting published traditionally, which I am now. That’s what I do, latest last few books were. But there’s a wanting of validation. That’s a big reason people go towards the publishers.

They want that validation and they feel that they’ll get it. They’ll feel that validation in themselves when a New York publisher says, ‘Yeah. We’ll take your book.’ I don’t think you can get that from other people until you give it to yourself.

When I published those essays without any gatekeeper, without even barely a proofreader, frankly, I didn’t finally find someone who would proofread them because I was putting them out so fast. I was saying to myself, ‘I don’t need to look to anybody.’

That really taught me how to work with traditional publishers to find the correct emotional set point to work with people in the traditional publishing world that I really got from being essentially self-published. Does that make sense?

Joanna: Absolutely. You mentioned validation there and, of course, this book. You’ve got a number of books, but this one is about the end of self-doubt and I feel what’s so interesting in the traditional industry is there’s a lot of rejection, as you mentioned, which amplifies self-doubt even further. So let’s get into it. What are the different aspects of when you might feel that way?

What are the different ways that authors might experience self-doubt?

William: I think it’s basically writing is like a task designed to confront your own feelings of self-doubt because you sit down and you face a blank page and really all you know is that you’re interested in the story. That’s all you know about the story, that you are interested. You don’t know who else is going to be interested in it.

You have to trust the fact that your interest in it is enough to, A, that that story is worthy of your attention and that if you’re interested, someone else might be interested, but it’s not known. That is a level of faith that you need because all you have is what’s inside you. So that’s where it starts.

The fact that you’re interested has to be enough. When I’m giving these talks, it’s like, that’s all Shakespeare got. That’s all Emily Dickinson, or Toni Morrison, or Stephen King, or Joanna Penn.

That’s all you get. Eventually, people start saying, ‘Oh, I really liked your stuff.’ That’s nice, but it doesn’t start there. Even if you get praise as a young person, is that step to professionalism? Does the praise you get from your teachers or parents or whoever, does it translate? Will it translate? And it’s very easy to question whether it would.

So I think it begins right away. It happens every time you reach the end of a sentence and you’re not sure what comes next. This is a common experience. You’re riding along, it’s going great, and then you’re not sure what comes next.

That is the moment where you also have to deal with self-doubt because you have to trust that the next idea will come, the next sentence will come. And if you begin to doubt that it will come, it won’t. Period.

As long as you are holding doubt that the next idea will come, it’s like you’re holding the door to where ideas come from closed. So you have to be in a constant trusting state to allow the ideas to come. Because if you knew the whole thing, you wouldn’t write it. You’re writing to discover.

And then, of course, rejection. I’m the editor of ‘Author Magazine’ so people send me ideas for articles. And I say no to some of them, to a lot of them. Sometimes it’s because they’re just not the kind of thing I want to publish. Sometimes it’s too similar to something I have published recently.

A lot of times it’s because the person writing the essay doesn’t really have a grasp on what makes a strong essay of this kind, particularly for what I’m looking for.

And so I have to say no. Sometimes I try to guide them, but it doesn’t really mean anything about them, but it’s very easy to assume when someone doesn’t want your work, that they don’t want you, that no one would want your work, that your work has no value.

I liken it to relationships. I’m married. I have been married for a long time, but I used to date a lot when I was a young fellow and I came to realize that when people break up, I really came to see it as the person who ended it, if it was one person, simply was the first one to recognize the relationship wasn’t working. I do not believe the relationship could be great and one person wants out.

I always think they just simply saw, this isn’t working. And so they ended it. I think that publishing is like that. You’re not looking for someone to validate you just the same way you wouldn’t look for a boyfriend, or girlfriend, or husband, or wife so you can feel good about yourself. You want a companion, you want a friend, and a publishing experience is a relationship.

In my case, if you’re traditionally published, you need to find someone who’s into what you’re into, who gets it, who is as excited as you are. And that’s a relationship. And that requires, Joanna, you to validate yourself, the value of what you’re offering.

Joanna: I think that finding someone who’s into what you’re into, it’s the same as an independent author, but we’re looking for readers.

William: Yeah. It’s the same thing.

Joanna: As an indie, you have to find readers who were into what you’re into. But it’s interesting around self-doubt because what you’ve been talking about there is almost within the writing process. And, in fact, I have on my wall here, a little sign that says “trust emergence,” as in, something’s going to emerge eventually if I just keep going through the page.

But then there’s also, I’ve written like 30-plus books now, and I’m going to write in a new genre and I feel massive self-doubt about writing a new genre because I feel like I’m starting all over again, I’m putting myself out there in a different way. I feel vulnerable about it. It’s going to have memoir in. So this is a lot of personal stuff.

Can there ever really be an end to self-doubt?

William: I think what it’s like is in my last book, Fearless Writing, I talked about mastery and I defined it this way. I tell this story, it’s a pretty famous story in the martial arts community.

I took Aikido and there’s the guy who founded Aikido was named Morihei Ueshiba, but they called him Ōsensei, meaning first teacher. Aikido is a defensive martial art and the whole key to it is staying balanced. If you’re in balance, then it’s very hard to knock you over and it’s very easy to throw someone who’s attacking you because attacks always put people off balance.

So whole point, you stay on balance, stay on balance, stay on balance. That’s the whole practice. There’s a story of where one of Ōsensei’s longtime students is watching him and he just can’t believe how grounded and balanced Ōsensei is.

Until finally the student comes up to him and says, ‘Ōsensei, I train every day. And every time I train, I am off balance and then I watch you and you are never off-balance. How do you do it?’ Ōsensei says, ‘Oh, no, no, no. I am frequently off-balanced. I am just very fast to get back on balance.’

What you’re wanting is the difference. It’s never going to happen that the thought won’t come into your head. What if I can’t do this, right? You can’t inoculate yourself against it, but you don’t have to spend days swimming around and wondering about the future. You can, with practice say, ‘I don’t know what’s going to happen, but I do know I’m interested. Is that enough? Can I be okay with that being enough? Not understanding what will happen with this book.’

That happens to me every time I write. I don’t know really what’s going to happen with this book. I don’t know where it’s going. I don’t know who’s going to buy it.

I interviewed Alice Hoffman who sold like what? Thirty books. I don’t think she’s ever been rejected. She’s had her movies made. She’s won rewards. And I was talking to her and she was like, ‘Every time I write a book, I think, I don’t know how to do this. I don’t know how to write a book.’

Every time she starts a new one and every time she’s in the middle, she thinks, ‘This is just not going to work. I won’t get it and no one will like it.’ And then she finishes it. So she’s going through that process again and again.

The question is how much time will you spend in self-doubt?

What I’ve realized is I’ve gotten faster and faster at letting that thought go, realizing there’s no way to answer it. There’s no way to answer that question, what will happen? You don’t know.

You’ve got to focus on what you do know and what you always know is, ‘I’m interested.’ But can I be more interested in how I translate this new idea than in who will like it?’ That’s down the road.

I’ll figure that out once I’m actually finished with it because, by the way, Joanna, until you finish the book, you don’t really know how to sell it, for instance. You’ve got to finish it. You got to know what the heck you’ve got.

Even though if you have a concept of it, I don’t think until you’ve reached the end, you really understand what you’re trying to write. And then you could have a sense of how you sell it.

It’s never going to go away, but you don’t have to wallow in it.

You don’t have to indulge the thought. You don’t have to answer the question, ‘What if no one likes it?’ You can’t answer it for one thing and you don’t even have to address it. Everyone has what it takes really is an attempt to address the question, what if I don’t have what it takes? And it’s an unanswerable question. The question you shouldn’t ever ask it, frankly.

Joanna: I think also sometimes self-doubt is justified. For example, when you write in your first novel, there’s a lot you need to learn. Or, in fact, even when you’re writing your 10th novel, there’s always something to learn. I think we need to recognize what category the self-doubt goes into.

William: I would just want to get rid of the word doubt. It’s semantics, but I will push back just a bit in that doubt is wondering… It is perfectly legitimate to say, ‘I don’t know how to do this. I have to learn. And I want to learn if I even want to do it.’

Am I interested enough to put the work in to figure it out? Because writing a novel is a whole thing. Writing a book is the whole thing. You don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to learn and you also got to learn if you want to do it.

Sometimes you’ve got to do it for six months to go like, ‘This is just not my thing. I’m not interested. I want to do something else.’ Like a relationship.

It is legitimate to say I don’t know, but you don’t have to doubt yourself. You’ve got to pay attention to what you do know, which is I’m interested, and that has to be enough to see how far can I go with this? Because the doubt is just saying, ‘Well, what if I don’t?’ But there’s no way to answer that. There’s no way to answer, ‘What if I can’t? What if I don’t?’

Until you get there and then you’ll know if you care, because I will say, because if you had told me… I didn’t publish my first book, really. And I started writing novels, books when I was 25 and I didn’t really publish till I was what? 50. Really.

If you had told me, ‘Okay, get ready. 20, 25 years,’ I would’ve said, ‘Just kill me now.’ I cannot do that. I will never be happy for that time. That is unlivable. But I was wrong.

If I said, ‘What if I don’t publish them?’ I wouldn’t have known how to answer. And I’d learned how to live and not publish them. I had to do it by experience. Does that make sense?

Joanna: Absolutely. I also do want to come back on the other bit of the title, is Everyone Has What It Takes. And again, this comes back to your relationship thing.

I’ve been doing this really since 2006, I started writing properly. And so many people have left the industry. So many writers, some people really do only have one book in them or they just decide, ‘I’m done.’

Does everyone really have what it takes? When is it okay to quit?

William: I was teaching this class on ‘Everyone Has What It Takes.’ And if I could have written the whole title, it would have been, ‘Everyone Has What It Takes To Succeed At The Thing They Love To Do.’

Everyone has what it takes to do the thing they love to do. It may not be writing. No, everyone does not have what it takes to be a writer because not everyone wants to write. Not everyone wants to sit alone in front of a blank page. There’s a lot of people who need the thing they do to involve other people and writing may eventually, but a lot of that time is spent without other people.

Everyone has what it takes to and if it’s just write one book, well, then that’s fine too. Like there’s no one career that is correct. You don’t have to write. It’s not fair to say that if you write three books a year, those books must be crap, or what’s wrong with you? You’re only producing one book every five years, you must be lazy.

Or what was wrong with the woman who wrote To Kill a Mockingbird? But she only wrote one. What’s up with JD Salinger? He quit publishing. There’s no one way to do it. I know people are all perfectly equipped to do the thing they absolutely want to do.

For instance, that sketch comedy show started because of poetry. And I ran out of poetry. I just stopped. When I tuned my dial to the poetry, they stopped coming. But suddenly, I was performing the poems and those became theater, became sketch comedy. It just evolved.

I saw the sketch comedy. I know it’s weird as an evolution of poetry readings in its own way. And so maybe it’ll change. I thought I was a novelist. I was sure I was a novelist. That was it. If you had told me what I was going to write, I would have said, ‘You are thinking of somebody else. I don’t even walk into that part of the bookstore. I want nothing to do with that kind of stuff.’

Now that’s what I do. I had to evolve and learn what it is I actually want to do. So I think everybody has what it takes to do the thing they love to do. Their job is to find what that is.

The poetry became theater because I was the performance side of it, I was really interested in and the novels became creative non-fiction. I knew I wanted to write when I was 25, but I didn’t really know what it was and I just chose fiction because that’s what I first was drawn to as a reader even though when I started writing fiction, I had stopped reading fiction.

If I was really tuned in, I would have noticed like, ‘That’s not where you are you’re at anymore,’ but I still stuck with it for 20 years. It was hard journey for me to come to finding what it is I really love to do.

What I say, when everyone has what it takes, you can’t sit around wondering if you have what it takes. You’ll never be able to answer that. The only question you can answer is, ‘What is so interesting to me?’ and that you have the answer to.

Joanna: And that changes over time. I think what you’ve said is really important. I always say to people, it’s more like skiing. It’s like a zigzag down the slope of life like you did. You’re like, ‘Okay. I like poetry.’ And then it’s like, ‘Hmm, not quite.’

I’m the same. I did poetry in my younger years and got published as a poet and then it disappeared. It wasn’t the thing. And then I went in another direction and now I’m about to start writing in another genre.

Is that what you’ve seen? You’ve interviewed so many writers as part of your ‘Author2Author’ podcast.

Have you seen this zigzag across people’s careers in general?

William: Sure. Some really they find their thing and they do it. It’s like science fiction, science fiction, science fiction, and that’s it. Or romance, romance, romance, but other people zigzag, yeah. Absolutely.

I always say your job isn’t to get out of your comfort zone. It’s to keep up with your comfort zone. I think it’s always moving. I think you’re always evolving and my job is to keep up with myself. My work is similar, but it’s changing.

The work I do now, it’s very similar because it’s about creativity and spirituality, but it’s growing and it’s evolving. I see it in the other writers I’ve interviewed, how it’s grown and changed. Sometimes changed dramatically and sometimes just change subtly because they’ve really found the thing they love to do. But absolutely. Absolutely, it changes. Sometimes subtly and sometimes absolutely dramatically.

I just interviewed one of my friends, David Laskin. He had been a journalist for a while. He had written a bunch of journalistic narratives, and some of have been bestsellers, and he’d done really well, but he made a huge switch and wrote his first novel at 65 or whatever.

He had tried to do it as a memoir and had gotten rejected. He got rejected for the first time in his long writing life. And he was very distraught, but he turned it into a novel and it’s doing great. That happened in his 60s. There was a huge departure, but he did it and it was fantastic.

So yeah, of course. People change it. You’ve got to follow yourself. You’ve got to be able to ask yourself, ‘What do I want now? What’s interesting to me now? I know this was interesting yesterday, but is it still interesting in the same way?

You’re like a tree that keeps growing. I was thinking the tree is such a great analogy. I’ve got one in my backyard, this apple tree. It’s complete, but it keeps growing. It’s a total tree. There’s nothing missing from it and yet it keeps changing. And I think we’re like that.

Joanna: Again, just coming back on all the authors you’ve interviewed:

What else have you seen in terms of commonalities of long-term success with a writing career, whether that might be practice, or business stuff?

William: It’s definitely: write the thing you love. That is the common thread through. I’ve interviewed writers, all shapes and sizes, romance, memoir, poetry, screenplays, literary fiction, whatever and it’s always, they just love the thing. They just love that story.

I think that is it. Love is the organizing principle of the universe, it’s the fuel that drives creativity, it’s the light that you follow through the jungle. It’s everything. So that is it.

What’s the story you love to read, you love to tell? What excites you? What story has your unconditional attention? What are you interested in just because you’re interested in it? That is absolutely the most common thing. All have that in common.

Everybody approaches business differently. Most of them have a writing routine, but not all of them. Some of them don’t.

I knew one woman who wrote novels and the way she wrote them is she only did the dialogue first. She just wrote complete dialogue and then she’d go back and put the prose. And I was like, ‘What?’ But yeah, that’s how she did it. So there’s no one way to write.

Although I would say do try to come up with a regular time to write if you can; it’s a good idea, but there are writers who say I do it on the airplane, I do it on the train. I do it wherever I can. So there’s always an exception.

The one thing that there is not an exception to, I think, is that the writer loves the story. I know that sounds pat, but you’ll never be better at anything than the thing you love to do, period. If you love doing it, that’s the best you’ll be. So find the story you love.

Joanna: I think that’s right. What’s interesting is obviously we’re recording this. We’re still in pandemic times and you write a lot about mindset and obviously creativity. And yet, even if we love writing, a lot of people have suffered from burnout, mental health issues.

I get my inspiration from traveling. So my well is dry, basically, which is one of the reasons I’m looking at different genres because I’m struggling with writing what I normally love. So how do we deal with this?

Should we just force ourselves into it or should we really listen to what’s going on and change what we do?

William: So the question is how do you deal with burnout? Because of the, say the circumstances we’re in. Is that what you’re asking?

Joanna: Exactly.

William: I think of conditions like a surface I stand on. So to go back to the Ōsensei metaphor, remember, he just wanted to be balanced. The conditions are like the surface. Sometimes I’m trying to walk on a balance beam and sometimes I’m standing on flat ground. I can always find my balance, but it’s easier.

So for you, your creativity, you discovered that you could be inspired by traveling. You found inspiration in that. I would posit to you, your inspiration comes from the same place everybody’s does, which is inside you.

It actually didn’t come from outside of you, but the experience was one that you found easily sent you into where inspiration was. I can never attribute my complete well-being to my conditions.

Now, there are conditions like being in the middle of a war zone that would be like walking a tight rope for me and I fall off a tight rope, but somewhere is someone who can be at peace in a war zone. I’m not that person now, but I didn’t think I was the person who could live with all that rejection and be okay. And I was.

To me, that was a tight rope and I fell off it, but I learned how to walk it. So I would say if you’re feeling down because conditions have changed, your situation has changed, you never want to feel that your happiness is dependent on something outside your own heart because that can always go away. And so I would say look in.

Maybe this opportunity to do this work is a way of teaching you that you’re even more creative than you thought, that you have a wellspring that doesn’t rely on that completely.

There’s nothing wrong with it. There are a lot of things I do which help bring out creativity in me, but I never want to mistake the activity for the creativity itself. I love to write. Writing is great. I love the experience, but still, it’s not the writing. I love. It’s where I go when I write.

It’s easiest to go there while writing, but I can go there just sitting in a chair by myself. It’s not dependent on the writing. The writing just helps me get there. We’re going deep here, Joanna, but I think that’s what you’re asking.

Do I need these conditions to be that way to be creative? And I say no. Let this experience be an opportunity to learn where your real creativity is, which is really always inside you. It’s always coming from within you. Does that make sense?

Joanna: It does. Although you also talked about, you have to follow your curiosity and what you love and what you’re curious about. I’m basically curious about places and historical things.

William: Here’s what I would say then. Then this is what you do too. Because that’s not going away, right? Obviously, that’s not going away that curiosity. You can’t make your curiosity go away. It doesn’t go anywhere.

Then you say, ‘Okay, so what do I do with that? I’m used to having the opportunity to literally physically go out and follow that curiosity across the globe. How does that curiosity express itself now?’ Maybe there’s a way to express itself that you simply haven’t found. You’re so used to being able to do it this other way for obvious reasons.

And, by the way, you’ll get to do it again. That’ll come back, but maybe there is another way for it to express itself that you haven’t discovered yet because you may not have asked the question. You may have assumed it had to go this way, that you simply never asked the question and so you didn’t discover the answer.

Joanna: In my case, I just decided to travel in my own country. So I’m writing books about my own country instead of other places. But I want to come back to what you said.

You said, ‘I have a lot of things I do that bring out creativity in me.’ What are those things?

William: Well, doing this. Honestly; conversations. I play the piano and I write music. That’s a hobby of mine that might’ve been a profession if I were slightly different person. So that for sure. I design games, I’m a game designer, role-playing games. And the podcast is creative.

I don’t prepare anything, but it doesn’t matter. Some people prepare, some people don’t, but I look upon it as just like let’s see what’s going to happen. I’m so interested to learn about this person. It’s what we call a co-creative experience. I feed off of them, they feed off of me.

Conversations, workshops, clients, all these things generate creativity in me because I have to think differently about that moment. I have to think differently about the client, I have to think differently about the guest, I have to think differently about the song I’m writing, the game I’m designing. All of it is creative.

Really, all of life is creative. The more I have learned to see my life away from the desk as no different from my life at the desk, the more I’m able to see myself as the author of my life, not just this person dealing with it, and managing it, and reacting to it, the better I’ve been. The more I can see the whole life experience as creative, like my life is a blank page, the happier I am and the more I thrive and the better husband, and father, and friend, I am. I always benefit when I see life itself as a creative act.

Joanna: I agree with you. I think there’s so much that can be creative. I guess obviously this show is very much about the business of being a writer as well as the art. And so there you talked about music, about game design.

Are these creative play activities or these creative business activities?

William: They’ve been both. I’m an award-winning game designer. We published a bunch of these things through our company, but I also do it for fun. The music is for fun, but I think I secretly wish it was a profession, but I’m shy about my voice, my singing voice, not my speaking voice, but my singing. So I haven’t allowed it to become more than an extremely prolific hobby.

I try to see all of my work as play as much as possible. I say everything I’m paid to do, I would happily do for free. I also like getting paid for it, but that’s my framework. I know how to work. I know how to do things that I don’t really want to do and get paid for it and I spent a long time doing that, and I’m not interested in that anymore.

Now I want to see how I can make money doing something that feels like fun. In fact, this is true. I was just doing, so recording the book yesterday at this lovely studio here in Seattle and so I go there and there’s the technician in there and then we’ve got this director who’s, I don’t know, in LA or something, we’re all wired together.

I’ve got my headphones on and, Will, the engineer, this really sweet guy, just as we’re about to start, he’s like, ‘Man, isn’t this fun? Guys, can you believe we get to be paid to do this? Isn’t this great?’ And I was like, ‘Man, he is singing my tune. He is singing my tune.’

Joanna: I’m with you. I love all this. I love the podcast as well. And I also think it is creative. It’s interesting how people seem to talk about podcasting as marketing, but I think you and I can see that it’s actually a creative process. And as you say, often I change my mind in talking to people or I get ideas when I’m talking to people.

In your ‘Author2Author Magazine’ and the podcast and everything, obviously book marketing is a practical part of the business. What are your thoughts on that? You are an author, you have the magazine, you have all this stuff.

What do you do for book marketing personally?

William: Actually one of my popular classes, Joanna, I teach is called ‘Fearless Marketing.’

Joanna: Wonderful.

William: What I always say when I teach the class is like I’m not going to actually teach you how to do any marketing. What I’m going to teach you to do is stop hating it because you can’t do it well until you stop hating it.

What I think about marketing, here’s the first thing I think of. I’m trying to define the conversation I’m offering. So I go to a writer’s conference. I like to go to writers, conference. Well, once again, I will go to them.

Every classroom is offering a different conversation. Some are talking about how to use social media, another one is like, how do you have a grabber opening? Mine is about the emotional challenges of writing. All the conversations are legitimate. How do you world-build all? These are good conversations for writers to have. This is the conversation I want to have.

I try to describe the conversation accurately in the little brochure and say, ‘Who wants to come?’ And people want to come. Here’s the conversation I’m interested in. And so that’s the first thing I think it’s really helpful for writers, define the conversation.

If you write romance, you want to be with other romance writers who want to think about romance in that way. They want to think about love and relationships in that way. I’m interested in creativity and spirituality. That’s a different conversation. You go to a party and it’s like they’re talking about politics over here, and soccer over there, and science-fiction over there. What conversation do you want to be a part of? That’s the first thing I say.

There are so many different ways to market yourself. Find the thing that you are most interested in.

I like to write essays, blogs. So I do that. And with the theory that if you like my blog, you might like my book. It’s the same kind of stuff. And if you listen to my podcast, technically, Joanna, my podcast, it’s my platform as you know, that word. My platform is just, I like talking to people who make stuff.

It took an agent saying, ‘Bill, you have a platform.’ I was like, ‘No, I don’t. I just have a bunch of things I like to do.’ And she said, ‘That’s a platform. What do you think a platform is?’ I do the things I like to do. I like talking to people in these interviews.

I like doing workshops for people and I like writing essays and I post them on Twitter, and Facebook, and Instagram. Now I’m figuring that out. But I let it be an expression of the stuff that interests me. There’s a lot of things you can do.

I knew someone who marketed his book by giving readings at dive bars. That was his big idea. And it worked for him. Another one did his readings on subways. He thought that was a great idea. I’d never do that, but he’ll love to do that. It sounded awful, but to him, it was an inspiration.

I would say to your listeners, try to approach marketing with as much creativity as you can. It’s great having someone like Joanna because you say, ‘I really want to dive into social media. That seems so cool.’

There are people like yourself or lots of people out there who say, ‘Okay. I will now teach you how to actually do it, but let’s figure out what you’re interested in.’ There’s no one right way to market a book, I don’t think, in the same way, there’s no right way to write a book. But you’ve got to find the thing that you think is cool about it and you can’t hate it.

You can’t turn your nose up at it. You can’t think it’s slimy. You can’t think, ‘Nobody wants to hear from me.’ You got to be as interested in, ‘How do I find the people who are interested in the same stuff I’m interested in? What would be the best way to describe this conversation such that people who are interested in it could recognize it as the kind of conversation they would want to have?’

That to me is the friendliest way to think about marketing because that’s really what it is. I’m on Twitter sometimes and people would basically saying, ‘Buy my book, buy my book.’ And I’m like, ‘That can’t work. What’s the what’s in it for me?’ I’ve got to know what I’m being offered in this experience you want me to pay for. What’s in it for me.

If I can define a conversation, and again, probably like your fiction writers won’t see it that way, but it is. It’s a conversation. You start a story, the reader finishes it. Think of all you have to leave out in your stories that the reader’s imagination fills in. That’s a conversation. So that’s how I would define it because then you know what it is you’re really offering the people that they’re getting from the experience.

Joanna: I like that you say define the conversation because I think for non-fiction it is a title.

William: It’s in the title, right?

Joanna: Yes. Your book title included the end of self-doubt and I’m like, ‘We should talk about that.’

For fiction, I almost feel it’s the promise of the genre, the title, the cover, the hook. You have to make it very clear what you’re offering and then someone chooses to join that conversation.

William: That’s right. I’ve worked a lot with writers and I find that that’s one of the most common things, is they don’t want to sell. They don’t see themselves as salespeople.

They see this odious and beneath them and it seems like they don’t like being sold but they do like having conversations they want to have. They’ve got to see it in a friendly way. Every book’s a conversation about something, about weakness and strength, about love or loss, about what’s cool.

It’s always about something. From a certain angle. And so define that for yourself. As an author, you are so interested in that conversation. There’s no way you can write a book and not be. And so you just got to know there’s other people out there who want to have that conversation too.

Joanna: Absolutely. Brilliant.

Where can people find you and your books and everything you do online?

William: The hub of my internet empire, Joanna, is williamkenower.com. So you can go there. And obviously, there’s links to books. There’s links to my podcast, to ‘Author Magazine,’ to my coaching.

If I remember, I post things I’m doing there in terms of like online workshops and stuff. I am a writing coach. I’m not a book editor, book doctor, but I do help people with their craft and also with the many, many emotional challenges writers face, like why should I do this? Am I any good? That’s sort of my sweet spot.

I work with people one-on-one with that. And, of course, it’s all over Zoom now. Anyway, go to williamkenower.com. And if you want to learn more, it’s all there.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Bill. That was great.

William: Thank you, Joanna. Keep doing what you’re doing. It’s awesome.

The post A Writer’s Guide To The End Of Self-Doubt With William Kenower first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn