Why is writing emotion so important in our books, whatever the genre? How can we create an emotional connection between our readers and our characters? Roz Morris gives her tips in this episode.

In the intro, how to get your indie book into schools [Self-Publishing Advice]; Did my bestselling book turn out to be a financial failure? [Tiago Forte]; How to Build a World Class Substack; Why did The Atlantic sign a licensing deal with OpenAI? [The Verge]; Like It or Not, Publishers Are Licensing Books for AI Training—And Using AI Themselves [Jane Friedman]; and my personal update post-Covid.

Write and format stunning books with Atticus. Create professional print books and eBooks easily with the all-in-one book writing software. Try it out at Atticus.io

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

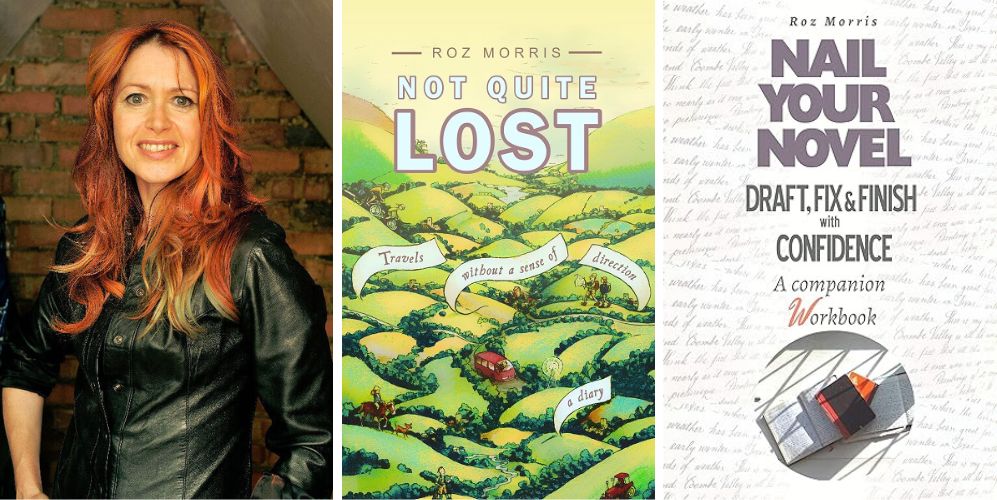

Roz Morris is an award-nominated literary fiction author, memoirist, and previously a bestselling ghostwriter. She writes writing craft books for authors under the Nail Your Novel brand, and is also an editor, speaker, and writing coach.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Why is writing emotion is so important?

- How can we create an emotional connection between our readers and our characters?

- How to write layers of emotion

- Using description and dialogue to evoke feelings in the reader

- “Show, don’t tell” when writing emotion

- Learning to lean into our intuition and trust more

- Using your own emotions and experiences in writing

- How and when to use a beat sheet

You can find Roz at RozMorris.org.

Transcript of Interview with Roz Morris

Joanna: Roz Morris is an award-nominated literary fiction author, memoirist, and previously a bestselling ghostwriter. She writes writing craft books for authors under the Nail Your Novel brand, and is also an editor, speaker, and writing coach. So welcome back to the show, Roz.

Roz: Hi, Jo. It’s so great to be here again.

Joanna: Yes, and you have been on the show many times before over the last 14 years.

Roz: I feel like we’re old timers, gosh.

Joanna: Oh, we are so old timers, but that’s because you’re so good at this, I wanted you back. The last time was in January 2023, when we talked about how to finally finish your book, which was a super popular episode. Though, given your many creative projects, what have you been working on in the last 18 months? Give us an idea of where you are in the creative cycle.

Roz: Well, just after that, I did an audiobook of my third novel. Then I was playing with ideas for another novel, and they sort of settled a bit, but I couldn’t figure out really what I wanted to do. Then another novel idea came along, and that’s starting to incubate.

Meanwhile, just as a kind of amuse-bouche, I’ve been writing a follow-up to my travel memoir, which is Not Quite Lost: Travels Without A Sense of Direction. So I’ve rather got the taste for writing little memoirs of un-adventures. I just really like them as a way of storytelling.

Joanna: Oh, that’s funny. Un-adventures, I do love that.

The audiobook, did you narrate that?

Roz: No, I didn’t. I managed to get back my narrator who did my first two novels because she just had such a good take and understanding of the material. She really wanted to do a third one if there was a possibility, so that worked really well.

Joanna: What about the travel memoir? Have you done that as an audiobook yourself?

Roz: I haven’t, but if there is an audiobook that, I want to do it.

Joanna: Yes, you must. You’ve got such a lovely voice. I do think memoir is one of those things, and your Nail Your Novel books as well. I think that these are some things, the nonfiction side, that we can do as authors more easily, I think.

Roz: I think so. Also, people get used to hearing the real us on podcasts like this, on videos that we appear on, when we speak in real life, and that sort of thing. So our genuine voice is really important there.

Joanna: Absolutely. Well, people should look forward to that at some point. Anyway, into our topic for today, we’re going to focus on writing emotion into our books, both for fiction and also for other genres like memoir and narrative nonfiction. So just to set the scene—

Why is writing emotion so important?

Roz: Well, readers love to feel. They absolutely wants to care about what happens. They love to be involved in what happens. Reading is a really intimate thing to do if you think about it. It’s just you and the author’s words, and yet it sort of goes into you and creates pictures and emotions.

So being in control of the emotion you are writing is a really important writing skill.

The emotion you write is closely linked to the genre. You have to know as a writer what emotion the reader of your genre is seeking.

Are they seeking thrills, or shivers, or a bit of romance? Do they want to be scared? What kind of scariness? Do they want a cozy level of scary? Or do they want something really dark that is something that speaks to them deeply? All that comes from writing emotion. Understanding what emotion the reader is looking for is the key to understanding your genre.

Joanna: It is fascinating. I was thinking about this because in my book Desecration, I wrote an emotion that I have never experienced, and some people did experience that themselves.

I was crying when I was writing it, and people did write to me that it was emotional for them. So I guess for me, I felt that was something I wanted to write about, but that I haven’t necessarily experienced, even though I kind of did as I was writing it.

Can we write about things we haven’t experienced ourselves?

Roz: We absolutely can. I did that with my novel Ever Rest. It has a lot about the grief of losing a companion, a close friend, a lover. I’m very lucky—I’m going to touch some wood right now—I’m very lucky it hasn’t happened to me, but I managed to find genuine place to understand the emotion.

Then, shortly after I published it, a reader contacted me and said her husband had just died and she was reading my book. I thought, oh, heavens, this is a real test.

She said, “You’ve got it. This is what I needed.” So we can seek understanding and empathy of situations we haven’t personally been in if we are perceptive, and truthful, and looking for the reality, and be sensitive.

So we can write things we haven’t personally experienced, but we can write them from a place of wanting to understand them. Here, actually, beta readers can be very important because you can bounce something off a beta reader and say, “Can you just look at this and check I’ve got the truth?”

Joanna: And of course, for my genre fiction, I was just thinking how ridiculous that question was as I was saying it. Like in my Catacomb, which is a horror book—I can’t say much without being a spoiler—but there are lots of things in genre fiction, in fantasy, also in romance, there’s lots of things that people haven’t experienced that they are writing about.

I guess it’s more cathartic for the reader because the reader doesn’t actually necessarily want to experience that either.

Roz: Yes, but they do want to feel this authenticity there. If you think about the word author, it has the word authority in it. They want to feel you are guiding them securely and with complete confidence through an experience.

Joanna: So let’s come back to that caring about what happens that you mentioned, and creating that emotional connection between a reader and our characters.

I know in a previous life you wrote some thrillers, and I obviously read thrillers. Sometimes I get really annoyed because I’m like, I really don’t care what happens to this character, it’s just action on action.

How do we create that emotional connection between a reader and our characters?

Roz: Well, that’s such a good point to raise because no matter what you’re writing, you want to make the reader care. Not necessarily care whether the person that they’re reading about lives or dies, but just care what happens next.

What you have to do is show why something matters. A mistake that I see in a lot of manuscripts that I’m given, is that we don’t understand why something matters. It’s as if I can feel the writer thinking, “Well, the reader will just assume it matters.”

Well, no, they won’t. They actually have to be educated at the start of the book about why a particular situation matters. Then much later on, they will understand why it matters, and you won’t have to do nearly so much explaining.

Then you can just get on with showing them things. They’ll know the characters as well as they would know a friend. They’ll think, oh, my goodness, that will really matter.

Joanna: I guess we need some more examples there in terms of some concrete ways. I think the word educating, although I know what you mean, to some people it might be sort of like, “Oh, do I need a big info dump about the backstory of this person and why this particular thing is so important?” So maybe just—

Give us an example of how educating a reader might work without an info dump.

Roz: Yes, that’s a very good point. You don’t have to do an info dump, you can actually just put in a few details that give context.

So for example, you might have a person looking out of the window, and they see a strange car drive up and stop near their house. They might think, “Oh, a strange car has driven up beside the house.”

Some writers might just leave it there, but a writer who is taking a bit more care about educating the reader—we’ll use that phrase—might linger a bit longer on what the person’s concerns are.

So this person looking out of the window and being worried might say, “A black car, I haven’t seen that car before. I was always told that when so-and-so’s people came, you wouldn’t recognize them.” Now that sets up worry, and you can see they’re worried. You can see they’ve got something in their past that they’re trying to run away from.

That will make the reader curious as well. They might think, oh, I’m maybe ready for a bit more about this. Now, you might not have to put that information in immediately. You might leave it until a couple of pages later, or you might say a little bit more there and then.

What you’ve done is you’ve shown a specific worry, a specific concern, about why that car has attracted this character’s attention.

Joanna: Yes, absolutely. The specifics of the situation are really important. Now, some people will worry about this likable character thing, as in—

Does a character have to be likable for us to care what happens to them in the story?

Roz: Not necessarily. They have to be curious about what will happen. They have to care what happens next. They don’t necessarily have to like the character, but they often have to see something that will make them a bit intrigued.

For instance, there’s a play I was just reading about called Skeleton Crew, which is by Dominique Morisseau. It’s about workers in a car factory in Detroit in the 1980s. To begin with, they’re all just working, they’re getting along, they’re being their tough everyday selves.

Really interestingly, in the descriptions of the characters, the author has put a little line about what, very deep down, they’ve got going on inside. So one of them always hoped she was made for better things. One of them always thought, oh, there’s something really bad inside me and I know it will come out in the end.

One of them always had this faith that the world would be a really lovely place and would be really good to her in the end. Those little pieces of information are under everything they do.

If you can then show that in their everyday lives they have some of that coming out and maybe influencing what they do, that might give them a little hint of vulnerability, which is very appealing to readers.

If readers see that someone has got something they care about, or something that might hurt them, something they’re protecting themselves against, while they may not necessarily be likable, the reader might understand that there is a piece of vulnerability in them.

That can make them very likable, even if they seem to be just ordinary, or in fact, maybe a bit badly behaved.

Joanna: Yes, the example I love to give is Succession, which is just one of my favorite series. Have you seen Succession?

Roz: Oh, I gobbled it up. When I was about to watch the last season, I watched all the others again. They are a brilliant example of characters who have all got this layer of vulnerability inside them.

Life could go badly wrong for them, and if you can give a hint of someone who is on the edge of life going badly wrong, that will count a long way towards making the reader just care about what happens to them, even if they wouldn’t like to have them as friends.

Joanna: Yes, and there’s not very many likeable characters in Succession, but boy, do you care what is what is going on there. I do think there’s so much emotion in that series. If people haven’t seen it, it really is a masterclass in subtext, as well, of like a family drama. Fascinating.

So let’s just dig down on the layers of emotion. You’ve talked before about the emotions we want readers to feel, but it’s not just love, it’s not just fear.

How do we dig down on those layers to make it more nuanced?

Roz: I think we have to approach every character as an individual. What we might do is consider, as we were talking, about the layers that they have underneath them.

We might have things we know about the characters that the characters don’t know about themselves, but they create a consistent pattern of interesting behavior.

We want to show interesting behavior and things that matter to them. So love might be a thing that matters to them, or feeling secure, or getting revenge. There are lots of big emotions that might come out of quite small, but very deeply seeded beginnings.

So if you look at the various deep seeds that you have in the characters and see what each person might do because of that, that can give you a lot of nuance.

Joanna: What about bringing in the various aspects of an emotion in a book?

So for example, if it is love of a partner, let’s say—you and I are both married—love of a husband is one aspect of love. But should people be incorporating elements of love of children, or of parents, or pets, or money, or a love of other bad things as well, to kind of bring some nuance to it?

Roz: What you often have in a narrative that’s got love as a theme, for instance, is a number of ways that love could be expressed in other ways in the story. So you might have good love and bad love, if it’s romantic love, for instance. You might have loyalty that isn’t romantic. You might explore an emotion in a lot of different ways.

If you give the reader lots of ways of experiencing that emotion, then that will add up to a thematic picture that makes them feel, oh, this book is about love or this book is about revenge.

Joanna: I’m coming back to your mis — un-adventures you called them. Un-adventures, not misadventures. The travel memoir, for example, and of course, I’ve written a travel memoir too, Pilgrimage. I certainly didn’t go into that with an emotion in mind. Did you go into yours with an emotion in mind?

If people are writing memoir or narrative nonfiction, how should they think about emotion there?

Roz: It was interesting. With that memoir, I had a series of stories and they were just personal diary entries. When I thought I might make these into a book, I had to see how I would make them interesting in any way to anybody who wasn’t me.

So what I did was I found that there were ways in which they were telling me something bigger about life. There were things that I wanted to bring out of them to show other people.

So for instance, the funny ways people behave if you go to a holiday town out of season. You just feel like you’re strangers, and you’re aliens, and you’ve wandered in there, and people treat you in a really weird way. It was a very small thing, but I found that interesting, the emotional effects of oh, this is how people treat you. That was just one of them.

Another one was there’s this country road that we really liked traveling. I was thinking, well, why does this really appeal to me? Does it appeal to anyone else? So I started digging and thinking, well, this appeals to me because there’s a real sense of history under the car wheels. So then I went on from there.

I looked for things that would take me to wider human experiences.

Not just my own particular experiences, but I started with the particular. Then I looked for things that were more widely recognizable.

Again, that’s what we can do in stories. The particular is very important. You can’t really get a reader to engage with generalizations. They need to see something specific and particular. So a particular character having a particular problem, a particular worry. Worries are really good for getting people curious.

Then from that they start to think, but wait, I know how that feels. I would hate to be in that situation, or I’d love to be in that situation. That’s another possibility.

So you start with something particular, and then you kind of work out how to make it something that a lot of people can understand and connect with. Connecting is another really important concept.

Joanna: As you were talking there, I was thinking about being an outsider in a town. I did a lot of solo traveling in my younger days, and I am kind of obsessed with this idea of the outsider, actually. Then I was thinking, well, what’s the name of the emotion? Is there one word? Or is it that we are actually looking for feelings, as you say?

Roz: I think it’s feelings. I think we don’t have to pin down a name. Maybe there is one, like loneliness-freude or something.

It’s more that we want to evoke the feeling. We don’t have to find one word for it, what we have to do is make the reader feel it themselves and understand what we’re feeling, what we’re noticing, that makes us feel like the outsider.

Here’s where description is really useful because you can use description to plug the reader into the specific emotions that are creating this whole experience. So for instance, you might be walking along thinking, “The sun is shining. It’s got no business to be shining because I’m about to do something that I’ve been dreading.”

Therefore, there’s a point in telling the reader the sun is shining. It wasn’t just, oh, the sun is shining because I’ve got to say something about what the day looks like. It’s that the sun is shining, and it’s making me realize that I don’t feel joyful at all.

On the other hand, if it’s raining and the sky is completely gray, but you’re thinking, “I don’t care because I’m just having such a brilliant time. I’m soaked to the skin, but I don’t mind because this place is just so refreshing. it’s zinging all my senses.”

Again, that’s a use of description, and it’s specific. It’s specific to a particular experience, and it involves the reader in what we’re feeling. So description is really important. You don’t have to know the word for it, the one word. What you do have to know is all the feelings you want the reader to understand when you drew their attention to a particular thing.

Joanna: Yes. Well, a few things to expand on there. So the first thing is how the character is feeling. When I re-edited my first novel, I did find that I’d written “feel” quite a lot. So, “Morgan felt something,” instead of describing more descriptive stuff around that, more details.

So maybe you could talk about “show, don’t tell” and having characters say, “I am angry,” or, “Ross was angry,” as opposed to what else.

How do we do “show, don’t tell” with emotion?

Roz: Well, “show, don’t tell” is a very important dramatic principle. It gives the reader an experience. You could say, “She got wet,” or you could say, “She walked along the street. The rain trickled down the back of her collar, it was freezing cold. Even her shoes were absolutely sodden and squelched with each step.”

That’s also, “she got wet.” That’s you understanding what it feels like to get wet. But the telling version is, “She got wet.”

Now, it’s a question of emphasis. Sometimes you don’t need the reader to feel what it’s like to get wet. Sometimes you just need to know she got wet, and then you move on because something else is more important. Sometimes it’s important to dwell in that moment and give the reader the experience of getting wet, or feeling angry, or noticing something.

Often when we self-edit, we come to a passage and we think, oh, should I give the reader more of an experience here? Or should I just gloss over it because it’s not so important?

It’s often quite hard, actually, first of all, to know when you’re showing and when you’re telling, and when you should show and when you should tell. You can look for certain phrases like “she felt,” and “she got angry,” or “she got calm.”

If you look for phrases like that where you’ve kind of been a bit distanced, you could ask yourself, would I like to see what it’s like if I just delve a bit more into the immediacy of the moment? So describe the feeling of anger, which might be someone saying, “I couldn’t stand it if she happened to mention such and such,” or something like that.

Joanna: I think that’s a good tip, actually. So really, when we talked before about the one word, so anger, and love, and grief, these are kind of the one words. If you find those one words in your manuscript, as well, “she loved him,” that can have so many deeper meanings that you really would want to expand in a lot of situations.

As you said, it is really hard, isn’t it? Especially for newer authors to know—

When do you just expand everything into “showing, not telling,” and when do you just gloss over that?

Do you have any other tips there? Because you also edit other people’s manuscripts, don’t you?

Roz: Yes, I do. It is a question of just thinking, how much do I want the reader involved in this? Or does it not really matter?

Sometimes you can just say, “They drove to Denver,” and that’s enough. You don’t have to tell the reader what it was like driving to Denver, but if it might enhance the manuscript to do that, have a go at telling them what it felt like to drive to Denver.

Sometimes in editing my own work, I’ll think, should I expand that or not? So I’ll try expanding it, and occasionally I’ll think, yes, that did work better. Or occasionally I’ll think, no, I don’t really need to dwell on that very much.

So sometimes you just have to experiment and think, is there more to find out about this that would actually make the book a better experience and would give the reader the experience that I am directing them towards?

You always have to be very conscious of where you’re directing the reader’s attention.

Joanna: Yes, it’s interesting, that “going home to Denver.” Immediately, in my mind, I was thinking of someone going back to maybe their childhood home in Denver, and that feeling that we all get when you go back to your childhood home.

Then that made me think that you’re not quite lost because you do go back to a childhood home. So again, it’s so interesting what comes up.

To me, as a discovery writer, this is the process. It is, what does it spark in your head, and is that something you want to tap into even further?

Did you mean to write nostalgia into that book?

Roz: I discovered it was there. That’s a really good point. With that particular piece that you’re talking about, I discovered that my childhood home had been knocked down. I was just seized with the need to write about it.

Then I thought, well, why will anyone else care about my childhood home? So I had to make each point something that I hoped people could understand and follow my feeling through.

So, yes, I just got this powerful sense of nostalgia, and I just wanted to explore that. Childhood homes always got that from everybody. It’s interesting that you picked up on that when I when I said, “Drive back to Denver.”

We all have our own resonances that we pick up on and emotions that we’re interested in.

That’s part of the delight of reading, that we get something very particular from a particular author, and another author might say something completely different about an experience. Again, that’s why particular is very important.

Joanna: Yes, and this comes to intuition, which I’m pretty obsessed with at the moment, in terms of trusting that story intuition. I think sometimes writers overcorrect themselves. They might think, oh, that wouldn’t be the thing to write here.

If you’re feeling any sensation, or draw, or curiosity to this thing, then that’s something you should write about.

You’ve been writing for a long time and you work with a lot of authors, how can we lean into that intuition and trust more?

Roz: I think it’s essential to do that. That’s where our style comes from. That’s where our originality comes from. It’s what moves us. I talked at the beginning about how the emotion that a reader gets is the genre, and that comes from what you are interested in and what you respond to as a human.

Joanna: Then I guess the other side of it is being careful, especially with emotional topics. You talked about grief before. Grief is obviously a big one. Relationships or family home can be very emotional.

How can authors use their emotion and their own experiences in their writing without getting overly dramatic or perhaps even hurting themselves in the process?

Roz: There are two aspects to this. There’s one aspect of how deep can you go while protecting yourself, and only you know that.

You can get yourself a safe space where you can just experiment on the page. No one else needs to see it, no one ever will need to see it, and you can just write without judgment. Just letting whatever comes come, and you can get rid of it, you can decide not to use it.

If you do this very emotional kind of exploration, you can get better and better at it in terms of just seeing what comes and then deciding, I may use this, I may not. It’s just something I’m doing privately between me and the screen.

If you’re writing something that is destined to be in a book which other people will ultimately read, remember, you can self-edit. Remember, all drafts are rough in some way. There are things that we sort out at all different stages of the writing.

So you might get the plot right first, or you might get the general style right first. There might be particular scenes that you’re always editing right up to the end because they are difficult for you to get right. No one else needs to know about all that, it just comes out to the reader perfectly in the end.

So you can edit any number of times. You can decide to try going deeper into a scene, you can then decide no, there was too much of that, but I might keep some of what I discovered as I was writing it. Discovery writing is a good phrase here, that phrase of yours. I think we can discovery edit.

Joanna: Yes, that’s interesting. Maybe the “on the train to Denver” situation, you might have just written that in your first draft, and then on your second pass you might actually realize that nostalgia is an important part.

It’s funny, again, what comes up in your mind. It made me think of Stranger Things. You know, Stranger Things, even though it’s a horror/sci-fi, actually, a lot of its success comes from nostalgia. There’s been a sort of revival of the 80s, and I know you’re a Kate Bush fan.

Roz: Absolutely.

Joanna: That song, was it “Running Up That Hill,” is that the song? It went to the top of the charts again, after something like 30 years. Bless her, she’s an independent artist.

Roz: She is the very epitome of independence. She absolutely set me on the path to being the kind of creator I wanted to be.

[Kate Bush] wrote what she was interested in, and she produced it herself, and yet, she’s an absolute icon for me.

Joanna: That song is so interesting because I wasn’t so into it at the beginning. Then I watched Stranger Things, and what they did with that—again, using TV, obviously, not a not a book, but a lot of people will have seen it—hooking nostalgia and care for that character. I think it’s Max, the character, and also the horror.

It’s a masterclass on how to mix various emotions into something much more powerful.

Connecting something to a song—and although remember everyone, you can’t use lyrics in your books, don’t use lyrics—but that kind of emotional resonance we get when we mix all that together, it’s just so powerful.

Roz: It is. Resonance is an important word. I was talking at the beginning about educating the reader and making them understand what a character feels about a particular thing.

Later in a book, as I said, the reader should know the characters well enough to be feeling alongside them, as though they were friends. So it has such powerful resonance, it’s like a song coming back.

They know, and they get the feelings, this instant rush of feeling. “Oh my goodness, if that happens, this will be awful.” Or, “This would be a dream come true.”

Joanna: Yes, another thing I was just thinking about there was the juxtaposition of emotions in genre. For example, in horror, you will often get a lighter scene, even some humor, to detract from the horror side of it.

I guess, again, Stranger Things would be a good example of that. You mentioned before being in control of the emotion—

You have to be really manipulative, don’t you?

Roz: Totally manipulative. I often think that writing is a conjuring trick that the writer is doing with the reader’s mind. You’re absolutely right that we have to vary the emotions and the pace and the intensity.

You need to give the reader a rest, otherwise they just feel remorselessly bludgeoned by strong emotions. So the scene where things are a bit calmer, and quieter, and maybe a bit humorous, is very important for just giving the reader time to recharge before they’re ready for another big thing.

Joanna: I mean, thinking again, Shonda Rhimes is really good at this. I mean, obviously, she’s a screenwriter and the showrunner. Bridgerton, she does it so well in Bridgerton.

Also, Grey’s Anatomy is the other one I was thinking of. You got this harrowing, people dying and everything, and then there’s some kind of light emotion that will make you laugh. I find that really hard though.

I find it very hard to put those lighter notes in darker books. Any tips for that?

Roz: Yes, I learned to do this a very long time ago when I was writing thrillers. I devised a system for figuring out exactly what I was doing with the emotion in each scene. It’s in my book Nail Your novel, the original one.

So I make a thing called a beat sheet. It’s a very detailed outline of the entire book, and I note all the emotions going on in the scenes. From that, I can see whether I’ve got enough of a variety of emotions, and also pacing as well, just to make sure the reader doesn’t get worn out before their time.

Joanna: That beat sheet, do you create that beforehand?

Are you an outliner, or do you do that later?

Roz: I am an outliner because I like to know where I’m going. I also give myself permission to veer off piste if something seizes me in the writing, and I think, oh, this is the true direction, I now have to do it. Then I might adjust my outline.

I find that if I write completely off into the sunset, I do get lost. So I do need to kind of pull the reins and bring myself back in.

I tend to make the beat sheet once I have got a finished manuscript. Then I use that to see what I should move around, what I should turn up. It’s a really good way of disassociating myself from the scene-by-scene words on the page and seeing what I’ve got.

Pacing is really important for emotion because you want to make sure that the reader is getting the right information. I keep using this term information, but you are giving the reader information.

You’re just giving them information they care about, and they want to know, and they’re really curious about. So you have to sort of be careful about the order you do all that in and how you handle it.

Joanna: Just to encourage everyone listening, this sounds complicated, but I do think that at heart, we are human, we are emotional.

So if you are writing with that authenticity, like you mentioned, or you’re making up that authenticity, because I haven’t been in many of the situations I write about, but I feel like you can use the editing process to fix this up. You’ve given a number of tips there.

I do want to come back to a couple of things. First of all, setting an atmosphere in emotion. So I want to come back to the example you gave earlier, the car outside on the road and the person looking out the window.

How can we use setting and atmosphere to enhance the emotions?

Roz: If I was writing it, I would think about what the weather was like and how that seemed to enhance or contrast with the worry that the character was feeling. I’d start with the character’s emotion, what are they feeling?

Then I’d have something like the sun glinting off a windscreen and think everything looks very normal in the street, but it’s actually not because there’s this really worrying car. I’d use the setting there to apparently be showing normality, but also highlighting the anxiety that the character is feeling.

Again, as I said, if you’re trying to provoke the readers emotions, description is really important for that. It should always be as relevant as possible for what the character is feeling, what you want the reader to be interested in.

Description for its own sake, that’s boring usually. Description for the sake of highlighting an emotion, or contrasting an emotion, or showing something impending, something worrying coming towards you for instance, that’s always really interesting to the readers.

You have to think, what will the reader be interested in?

Joanna: Yes, and certainly genre plays a big part, as you mentioned. So, for me, there are storms on the horizon or the clouds that are black in the distance. There’s lots of words for different colors you can use that are quite suspenseful, or quite horror, or quite thriller.

It would be very different if you were writing romance. You would use the weather and the setting in a different way. In fact, coming back to Stranger Things, they do this in the upside down. You might have a dead tree instead of a tree in bloom, and with flowers, and leaves and things.

So using that setting to portray the genre and the emotion at the heart of the genre, I think can be really powerful. Sometimes I feel like people worry, oh, I can’t have a storm coming or black clouds because that’s cliche.

As a reader, I see that as a signal of the story, and I almost expect that. Like if you’re going to give me a horror novel with a climax, and there’s no rain or thunderstorms or dramatic weather, then I might be disappointed.

Roz: Yes, and it’s so genre specific as well. So if you’re writing a haunted house story, then a crash upstairs is really a sign of trouble. If you’re writing something cozier, then a crash upstairs is the wardrobe collapsing.

Joanna: Because the cat jumped off in a funny way.

Roz: Exactly. So all these noises, all these scene setting details, have their own vocabulary in different genres.

Something else that’s really important is the language you use. The language is so evocative. By itself, a word can create a whole feeling. If you use a word like squash, you wouldn’t really use that if you wanted to be serious or dark.

Joanna: Unless it’s Halloween, and it’s like a pumpkin squash.

Roz: Even then I would probably say gourd because of the shape of the word. Every single word creates an atmosphere.

Joanna: I also wanted to ask about authors who might struggle to tap into their emotions, or they kind of know what they’re feeling, but they don’t really know how to describe it.

What are some ideas or tools for people who are struggling to name or write about what they’re feeling?

Roz: First of all, that struggle is really interesting. Embrace it, because it shows that there is something you want to do, and you want to find out how to do it.

I often find myself thinking, I’m not describing this well and I’m not quite evoking this as well as I would like to. So I read other people who’ve done it well, and obviously not to copy them, but just to see how they did it.

So much of the stuff we read, we have no idea really what the author is doing with us, we just know they’ve done it. It’s good to just go and study something that works on you really well. Think, what vocabulary did they use to make me feel that? What setup did they use earlier in the text, or maybe in the whole book, to bring me to this feeling?

So that’s really important. I often find I just want to go and read somebody, even though I know what the book is and what’s going to happen. I’ll go back and read it and think, how did they do that particular thing? There’s always something to learn from a book you’ve enjoyed.

The other thing is, it’s practice as well. Don’t be afraid of writing something that’s bad at first. As I said, it’s private for you, nobody’s going to see it. All sorts of artists in all disciplines do roughs, where they’re doing rubbish before they get to something that’s good and usable.

Just experiment, and you’ll get better at it, you’ll get faster at it.

You’ll get to the stage faster where you think, okay, this is usable, or that’s not going anywhere, so I won’t do that anymore. It’s practice really.

Joanna: Yes, and as you say, noticing how other people write things, and then how you feel, and then more nuanced stuff. So again, I was just thinking of The Crown, which is a fantastic series.

There was one scene, I didn’t even notice it but Jonathan, my husband, did. In one scene, I think it was with Diana and the rest of the Royals, there was a basket of snakes, like a basket of stuffed snakes, like right there on the screen.

I didn’t even notice it, but it was one of those almost subtext atmosphere things that your subconscious would have noticed and felt a particular way about. Like you obviously would feel scared of a basket of snakes, or you’d feel like that whole thing about betrayal.

There’s so much there that’s rich that you might not have even noticed the first time around. If anyone is going to now watch The Crown, keep an eye out for that. I mean, that’s a real advanced technique.

Roz: I will definitely keep an eye out for that. I haven’t got to that bit of it yet.

Yes, that is an advanced technique, something like that. It apparently looks like they just put something there because they had to put something there, but they didn’t, they thought very carefully, what am I going to put there? I’ll put a basket of snakes, great.

Joanna: Yes, I love it. We can do that in our writing. You can just have something, like you walk through a room, but the things you write about that the character sees, some of those are going to give that kind of impression as well.

Roz: They will notice things that seem to be significant to their state at the time. As I was saying with the weather, they’ll notice if it’s making them uncomfortable, or they’ll notice if it’s making them feel life is good. They’ll notice something odd, like there’s a basket of snakes in the corner, why?

Joanna: What kind of house am I in?!

Roz: Something we haven’t talked about is dialogue, because —

If you really want to get the reader involved, which emotion is all about, dialogue is a great way to do that.

You can get the reader to a state where you can have a few characters talking, and they are reading between the lines. They understand what something means to one person and what it means to another person. They understand if there’s an awkward pause, that this might mean something. It might mean there’s a danger area.

Dialogue is really important for getting across emotion and getting the reader immediately involved in the intensity of an emotion that’s going on.

Joanna: Yes, and again, I’ll come back to Succession on that. I actually heard that the writers’ room, they actually filled with playwrights. Ones who were really used to doing dramatic theater which, of course, is dialogue heavy.

So I thought that was really interesting because in live theater, you don’t get to do so much in terms of special effects, or changing the scenery, and all of that kind of thing. So the words have to do a lot of the heavy lifting. I definitely struggle with dialogue more than anything.

Any tips for emotion in dialogue?

Roz: I do find that I have to go over dialogue scenes again and again. That is because I love getting the nuance of it exactly right, and the performance.

What I often do is I take a lot of the verbal words out that the characters are saying to each other, and I try to put in more gestures and silences and maybe a little bit of something in the environment that seems to enhance what’s going on. Say, a picture on the wall that a character notices and thinks, “Oh, that thing is so ugly.”

That’s actually saying something about what they’re feeling about being in the scene with that person. I love all those subtleties, but it does take a lot of time to get a dialogue scene right. So it may be that you’re just doing them properly.

Joanna: Well, there have been lots of tips today.

Where can people find you and your books online in order to learn more?

Roz: You can find my website, that’s probably the easiest way. It’s RozMorris.org.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Roz. That was that was great as ever.

Roz: Thank you for having me.

The post Writing Emotion With Roz Morris first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn