Who are the Choctaw people and how can authors write authentic Native Americans in their books? How can we research diverse characters and include a diverse cast without worrying about cancel culture? Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer talks about how her Choctaw heritage influences her books.

In the intro, the Pilgrimage Kickstarter is done — thanks to all backers and I’ll be in touch soon; With a Demon’s Eye on my store and pre-order elsewhere; Opportunities in 2023 [Ask ALLi Podcast].

Today’s show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, where you can get free ebook formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Get your free Author Marketing Guide at draft2digital.com/penn

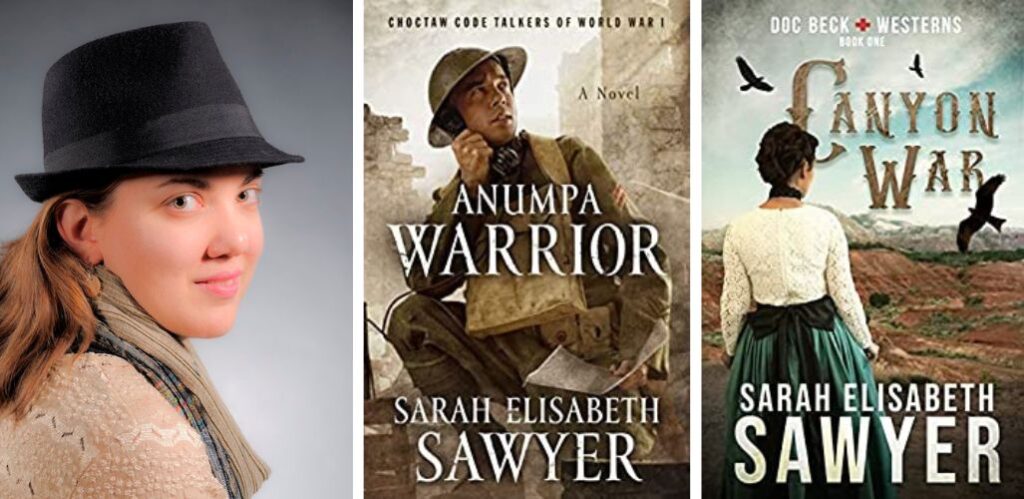

Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer is a historical fiction author, speaker, course creator and Choctaw storyteller. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian honored her as a literary artist for her work in preserving Choctaw Trail of Tears stories, and she is the creator of the Fiction Writing: American Indians digital course.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Who are the Choctaw people?

- How to include representation without being stereotypical

- Researching cultural callbacks to include in your writing

- How to use oral history from tribes in your research

- Writing diverse characters outside of our personal experience

- Creating well-rounded characters when writing diversity

You can find Sarah at ChoctawSpirit.com or her course at AmericanIndians.FictionCourses.com

Image generated by Joanna Penn on Midjourney.

Transcript of Interview with Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer

Joanna: Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer is a historical fiction author, speaker, course creator and Choctaw storyteller. The Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian honored her as a literary artist for her work in preserving Choctaw Trail of Tears stories. And she is the creator of the Fiction Writing: American Indians digital course. So welcome to the show, Sarah.

Sarah: Thank you, Joanna. Halito. Sv hohchifo yvt Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer. Chahta Sia Hoke. Hi, everyone. My name is Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer, and I am Choctaw. And it’s just such a delight to be on your podcast, Joanna.

Joanna: I love that. And of course, we have listeners from over 200 countries.

Perhaps you can first explain, what is Choctaw, anyway? And how does that relate to your writing?

Also, please advise on the preferred terminology because we mentioned American Indian, which I thought was not allowed anymore. So tell us about that.

Sarah: Oh, I will try to give you the short answer on that one, but let me first tell you about Choctaws and my Choctaw people.

So we are an American Indian tribe, originally in the southeastern United States. Primarily Mississippi was our homelands, and that’s where my ancestors came from before we were forced to basically sign a treaty, the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek, which ceded the last of the Choctaw homelands for lands in Indian Territory, or what is now the state of Oklahoma.

So we had the Trail of Tears in the 1830s, where about 20,000 Choctaws were removed and came across the trail over 400 miles to the new homelands. And it is estimated that around 2000 died, and that’s why it became known as a Trail of Tears and Death.

Thankfully, our Choctaw people are very resilient, and we rebuilt the tribe and the nation to what is now the Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. And we’re the third largest federally recognized tribe in the United States.

There are also still the Mississippi Choctaws, the Mississippi Band of Choctaws, who remained in Mississippi and were federally recognized in the 20th century. And we have some pockets of Choctaws really everywhere.

I meet Choctaws everywhere that I go. There’s a large contingent in California, during the Dust Bowl, the 1930s, many of them migrated out from Oklahoma. But there were over 500 nations here in America prior to European contact. So the Choctaws were among that, but each tribe were distinct.

And how that relates to my writing, I have seven Choctaw, what I call my Choctaw Heritage books, where I feature our Choctaw history and culture. I do a lot of research and interviews, and we’ll get into that a little bit later.

I have seven of those books that I’ve based around my Choctaw history and culture.

The terminology, boy, that’s the big question. And you’re going to get different answers depending on who you speak with.

So I did decide to title my course, Fiction Writing: American Indians. That’s still one of the really dominant terms in Indian country. We say, the National Museum of American Indian, and there are just tons of organizations that still go with American Indian.

Native American is considered the politically correct term. A lot of natives do reject that term. And then you’ll meet those that completely reject the term American Indian and are offended whenever I use that sometimes.

So the term Indian itself alone has been so abused and used derogatorily, that you just have to be careful and really understand how and why you’re using it.

And so actually, my favorite terminology right now is First Americans. And we have the First American Museum in Oklahoma City that opened up recently, and I love that they went with that name. But depending on who you’re asking, you’ll get a different answer.

Now, the most correct way, like for me, I don’t necessarily say typically that I’m American Indian, or I’m Native American, I say I am Choctaw. And that’s the most correct way to refer to someone is by their tribal affiliation, if you can.

Joanna: And forgive me, I just don’t know much about this. And I’m sure some people listening don’t either. I mean, we have in our mind a sort of monolithic group of people, and I know of some tribes, but I’d never heard of Choctaw before you emailed me. And I was like, wow, okay. I think we hear about like Navajo, for example, as a sort of one. I think probably because I’ve been to the Grand Canyon and stuff like that.

So I feel like for many people listening, this might be the first time. But it’s the same in a lot of different countries, right? There might be an indigenous people, but they will be made up of lots of different people. Like for example, on my Books and Travel Podcast has an Australian Aboriginal lady and they also have hundreds of different groups and lots of different languages.

So I love that you shared your language there as well. So you’ve told us a bit more about your Choctaw side, but —

Tell us a bit more about how you got into writing and a bit more about your history.

Sarah: Oh, absolutely. I’m one of those that I always knew I wanted to be a writer. I know some people discover that later in life. I’m just one of those that when I was five, I wrote my first story.

And it was just little blocks of sentences, I wrote them on sticky notes, and my brother illustrated it, but I had a story about kindness. And I was so shy, I knew I would not be able to ever say it, never be able to speak it. And so I wrote it down as a story.

I just continued writing through childhood and my teen years, and got away from it a bit. And then when I was 23, over a decade ago, I can say, God brought writing back into my life, and I joined an association that we did flash fiction every week. So I wrote over 60 of those, all different genres, really just exploring my voice and my style as a writer. And in 2013, I got into indie publishing and haven’t looked back.

Joanna: That’s great. It’s fantastic. Actually, I was going to say around the American Indian thing, is that it’s almost this sort of search engine optimization because that’s still the term that people might search for.

In the same way — well, not in the same way — but similarly, self-publishing. A lot of us use the term self-publishing, even though we don’t do it ourselves, because people actually search for it and that’s what they ask about.

Whereas you just said ‘indie publishing,’ and that’s what we say within the group, but outside the group, people say self-publishing.

So I imagine it’s kind of the same. It’s like when you’re in the group, you have different language to outside the group. So all of this is words and understanding. It’s so interesting.

We are talking about this idea of heritage today. And of course, there are lots of people of different races and groups who don’t write about their heritage, or may write a sort of bigger American story or not about a specific group.

Why is writing about your heritage so important to you?

Sarah: That’s an excellent question. I love that one. Because that is when I began my writing career in earnest, that’s what I was drawn to. I wanted to write Trail of Tears stories. The biggest example I can give you, though, is Choctaws, like our history and culture is so familiar to us, but there are people who around the world like you that have never even heard of the Choctaw people.

For me, most of the stereotypes and the conceptions that people have about indigenous people, and especially Native Americans, American Indians, comes from media, it comes from entertainment. And that’s how we influence culture. And so since people didn’t know about my history and culture, very specifically the Choctaw Code Talkers of World War I.

So a lot of people have heard of the Navajo, you mentioned the Navajos, and they are one of the largest tribes in the United States. And they had the Navajo Code Talkers in the Marines during World War II, but very few people know that code talking started in World War I and the Choctaws were among the first, and really the only ones, who developed an actual code during World War I, there in France.

I would ask people that and no one had heard of them, and I was like, I have to write this as a story, I have to get it out there in the mainstream to educate people to let them know about the Choctaw people and our heritage, and let them experience that through fiction. And that’s what I’ve set out to do with many of my stories.

Joanna: And I mean, I guess people can write, as you have, a specific story about the people in that way, but I guess other writers might include a character with that history.

For example, I don’t write specifically LGBTQ queer fiction, but I have characters where a woman loves a woman, for example, or I have characters who are different to my own situation. And I don’t make a big deal about that side of them, that’s just them. And I don’t want to focus on that in the story, it’s just they’re a person so they have that as part of them.

If people listening want to incorporate heritage, but not overstate it, what are your tips about that?

I guess it’s about representation.

How can we put people from all different groups into books so they’re represented as different types of normal jobs and all of that, so it’s not questioned that a Choctaw person is whatever they are?

Sarah: Exactly. There’s so much to unpack with that because we’ve had a lot of discussions about that. And my friend and I, Molly reader, she’s an excellent writer in her own right, and she does fantasy and science fiction. And so we had a discussion, a webinar with those writers of that genre, and that’s something we were talking about is not putting in native characters for the sake of diversity, like make them real characters.

So that’s something that I think we need diverse characters and a diverse cast, I think that’s awesome. Just make sure they’re developed, like you said, as a character living their lives and going about their work, and they happen to also be Choctaw. It doesn’t have to be specifically centered around that heritage.

An example I have of that is my Doc Beck Westerns series. And Doc Beck is an Omaha Indian woman doctor. And she’s loosely based, her background is based on the real Dr. Susan La Flesche who was an Omaha Indian woman doctor in the 1890s.

And so I took that character, but I put her in a completely different situation. It’s more about her being a female doctor in the old west in this more male dominated world. And so she has these adventures, it’s more like an old TV Western.

So her heritage is definitely a part of her, and it ties strongly into the last four books of the series, but the primary thing is that she’s a doctor. And she’s going about her work and relationships more as a woman in the old west, rather than specifically bringing out the Omaha Indian aspect of it.

So I think writers should definitely have that diverse cast.

If you want to focus on the heritage of a specific cultural group, just make them real people.

And that’s the biggest stereotype that we see with a lot of natives, like you have the wise guide. And so you have this native character, and they’re always in this role of being the wise guide or in advising the character.

And so I think just having them in normal character positions is really a way to avoid that stereotype because it doesn’t have to be just about their heritage to have that diversity in your cast.

Joanna: You mentioned sci fi there, I mean, the captain of the ship can be a female Choctaw. That’s what makes it interesting. And also in science fiction is a message of hope, which is we’re still alive in the future.

And I guess part of your reason for writing your heritage is you want your nation to continue into the science fiction. You want there to be Choctaw space captains in the future.

So I think this is what it’s about, for me anyway, in terms of trying to put different people in different roles is that this is only one aspect of them, isn’t it?

If people wanted to put a Choctaw character in their book, are there any specific cultural callbacks that they might have that mark them out?

Are there any things you would read in a book and go, yeah, that is a Choctaw character without them obviously saying, “I am Choctaw.”

Sarah: I love that. That’s actually a really good point that would be good to mark here. Like I said, there were 500 nations and we’re all distinct people.

So people right now may be thinking of Choctaws and teepees and buffaloes, and we didn’t live in teepees. We lived in what we called chukkas, which were winter homes. We had summer homes which were log and chink structures.

So we were agrarian. Primarily there is buffalo back there in our history and all, but we weren’t like the Plains tribes that followed the Buffalo and went on the summer buffalo hunts. That wasn’t primarily Choctaw.

So we see that a lot, and I’ve had our history department tell me that people will send in books and stories to them, basically wanting an endorsement, per se. And they’re like, we would have to rewrite this whole book to make it Choctaw because they’re so heavily influenced by the mainstream stereotypes of what people think indigenous people or American Indians are.

And so with Choctaws, for me, like if I saw someone in regalia, in traditional dress, I would know whether they were Choctaw or not based on what they were wearing. We have the distinct diamond pattern that you’ll see on our shirts and our dresses, and that’s to represent the diamondback rattlesnake.

We have distinct dances and songs. So if someone were to put that in there that they were Choctaw, I wouldn’t even mind if the character said their Choctaw, but you definitely want to show versus tell. And that just goes to doing your research and going to events. I tell that to people a lot.

And what you said about, you know, that we’re still here. That’s a big thing is people think of American Indians in the past, and we’re still here. So if you can go to a powwow, there’s protocol and things to follow, but go to Choctaw events, go to native events, and learn about the individual cultures, rather than just the blanket indigenous people stereotypes that we tend to fall into.

And I even fell into them whenever I was first writing, and thankfully, my mother’s on it, and she pointed out some things to me that were stereotypical. And I was like, oh, right, duh. That’s not very good representation as a Choctaw. So yeah, if someone wants to write specifically about Choctaws, get to know the Choctaw people.

Joanna: And so you mentioned there’s a diamond pattern and the rattlesnake. So, again, we’re just going to use the science fiction captain of the spaceship, because then perhaps I could have some kind of diamond pattern on the uniform.

Or he or she could wear like, I don’t know, some piece of jewelry with the rattlesnake on, or something that was a callback. Or the colors, you mentioned the traditional dress, presumably there are certain dyes, certain colors that would have been used in the dress. Would that be correct?

Sarah: And we also have a lot of beadwork artists today that they make these beautiful medallions. And that’s what a lot of Choctaws wear with their regalia. We have beaded collars that go over the dresses.

So there’s tons of aspects like that, that you could absolutely incorporate into the spaceship captain’s uniform. I have a science fiction story series tucked way back in the corner, Joanna, I don’t know if it’ll ever emerge, but it’s tucked way, way back there. But yeah, it’s fun things like that, a patch with the diamond design. So I could definitely see them incorporating their culture into their work that they’re doing.

Joanna: And I think that’s what is important, too, is kind of using proper elements from a culture. And it’s these little details that make it clear that we’ve done our research. So let’s talk about research.

How do you recommend authors research? And how do you research your own books to ensure accuracy?

Sarah: Excellent. Accuracy is such a huge part of what I do because there is so much inaccuracy out there around American Indians and around Choctaw. So I spend a great deal of time on research.

For the writers listening, if you hate research, that’s basically where I started. I didn’t hate research, I liked going and talking to people and going to events and that type of thing, but when it gets to the nitty gritty of how did they develop a photograph in a dark room in 1890, that just drives me nuts.

The bigger aspects of it, researching the culture, I love talking to elders, that’s one of the things — and I say talking to them, I listen. Usually you can ask just one or two questions, and you’ll get a whole ton of insight. And just hearing their voices and hearing the way they phrase things, those things just tuck in the back of my mind and end up in dialogue and that sort of thing.

For my research on the Choctaw Code Talkers of World War I, Anumpa Warrior, my novel that came out in 2018, I actually got to travel to France which was marvelous. It was my first international trip, and I got to go to the battlefields where they fought. And what was really amazing about that trip is, even though I was researching mostly general World War I history, I got to experience the way that the Choctaw would have in a lot of instances.

I even had someone who asked when we told him a little bit about the Code Talker story, they were like, “Oh, did they send smoke signals?” And I was like, “No, no, it was telephone.”

But even that, having the experience of stereotypes going before them. And that’s what they experienced when they went to France in 1918, is they had all these stereotypes that they were meeting with the French and the German and the British, who they had their perceptions of what American Indians and what Choctaws were.

So research, with that one I had over 100 people in the acknowledgments. I went to the National Archives, the military records, and I worked with tons of historians and military experts.

The main thing for writers who are looking into that, is try to connect with the tribes. So some have cultural departments or historic preservation departments or language departments.

A caveat to that is it can be difficult to get in because so much has been taken from Native Americans, so much has been taken and stolen from our communities, that you’ll find some native people, probably many, who are guarded and who want to know what you’re using this for and are hesitant about giving information because so much has been taken and abused and misused.

So that does take time, and I cover that in my course of some ways that you can do that. But that’s really the best thing is to go to the source.

Go to the tribe as best you can, and whatever they’ve preserved, try to base your work on that.

Joanna: Yes, and I think there’s a lot of recordings, oral history recordings, as well because now everyone lives a very modern life, but there are often oral histories you can find.

Certainly here in the UK, there are probably recordings of Native Americans as well that you can get just from the British Library. I’m sure your Library of Congress or whatever has recordings and things. I’m glad you got to go in person. I’ve been to those World War I battlefields, super depressing, but good to research.

Let’s just talk about some of the stereotypes. So when you mentioned the wise guide, I was thinking of — Do you know the movie Legends of the Fall?

Sarah: No, I’m not familiar with that.

Joanna: Well, it’s a classic kind of family living out on a ranch, and they have Native American people who live on and work on the farm. And the eldest man is exactly that, you know, he does the smoke and everything. It’s an older film, it’s probably the mid 80s or early 90s. And his character is very evocative, he’s a good character, and you love this character. So you have a very positive view of him.

But much media of Native Americans is the kind of whooping, horseback, Tomahawk, killing-all-the-white-people type of stereotype, which is what you see in a lot of Westerns, with the older Westerns, I guess.

Do you have any movies or TV shows or media that people could watch where you feel that Native Americans of any tribe are represented in a way that is more correct or respectful?

Sarah: Now, that’s excellent. As you said, the westerns, and I grew up on westerns, and my papaw, who I get my Choctaw heritage through, he was a huge Western fanatic. He loved all of it, my dad did, and so that’s what I grew up on.

And that’s why I created the Doc Beck western series, is I wanted to explore the western genre, but I wanted to have that non stereotypical respectful representation of an American Indian in the lead role. I really wanted that as well, and so it really worked out to do the Doc Beck with this female Omaha, Indian woman doctor.

I think there’s more negative representations than well done representations in movies and TV shows. I’m not real hip on a lot of the contemporary movies and stuff that are coming out, even in the historical genre. I know in a really popular TV show right now, there was even some controversy because they have a Lakota actor who is portraying one of the characters, and he did a sacred ceremony with one of the white characters on the TV show. And the Lakota Council, their Cultural Council, was actually upset about that. And people can go find the article on that.

So even whenever you have actors who are representing and bringing that aspect of it, you still have to look at it as a whole. And you’re going to have conflict of what can be shared and what can’t be shared on that.

I would recommend, right now I love what the Chickasaw Nation is doing, and this is something that is not mainstream and you have to dig for it, but I think your listeners would really enjoy looking at some of their films. They have a production company now and I love what they’re doing. Their newest one is Montford: The Chickasaw Rancher, and so he’s a Chickasaw rancher, and I love how they portray his character. It’s based on a real person from the 1800s.

I would recommend you to check out some films that have been made by Native people.

And I know the Chickasaws, and I think the Cherokees and some others have done it and done it well, as well, the Chickasaw Nation has a publishing company called the Chickasaw Press. And I’m contracted with a book with them right now.

So I love when the tribes are putting it out there, and not saying that it’s going to be perfect or there won’t be controversy around it, but you are really getting that Native perspective. And there’s something different about that. And that’s not to say non-natives can’t write really well done non-stereotypical stories like that, but if you can find some that are done by tribes, that’s really awesome.

Joanna: Personally, I feel that’s also research. Like if I, as a British white woman, want to include my Choctaw science fiction space captain, then for me to read books by Native American people will give me ideas that are better than potentially reading a Western by a British white man.

It’s important to talk about this even if you’re worried about cancel culture.

And the thing is, as we’re talking about this, this discussion is difficult and we mentioned this before we came on the call, is that there is, at the moment, a cancel culture or the way that people feel like, ‘oh, I don’t want to do that in case I get attacked, or in case I get taken down,’ or in case someone takes offense at me.

I might try the best I possibly can, and then someone will find an issue and say I’m racist, or they’ll take something out of context.

I’ve had this happen to me. My husband is Jewish, and I write about Jews and Israel. I am not Jewish, and I had someone accuse me of being a Nazi because they took a quote from one of my books completely out of context, put it on Twitter, and accused me of being like an ultra-right wing, Nazi, antisemitic, etc.

And I’m like, seriously, if you’d actually read the rest of the book, you would understand that that was about as far away from me as you can get. Now that’s just a personal example. And yet, I deliberately include people of lots of different cultures in my books because I think it’s so important.

So what are your thoughts on writing diverse characters outside of our personal experience?

Sarah: That is the hot topic today, and there’s so much controversy around it. And it was so much, that I had wanted to create the course that I did for many years, but it that was one of the hesitancies because it is so controversial.

And there are many native authors who don’t want non-natives writing our history and culture. And we have the Own Voices movement and those types of things, and I think that’s wonderful. I mean, natives, we need to write our history and culture.

I also wouldn’t block, you know, from the other side, as a writer, I understand that we explore all different cultures, and histories, and experiences that are not our own.

I write from the male perspective. I have Jewish characters, I have black characters, I have Indian characters, all in my Choctaw Tribune series. I have diverse characters, I have diverse friends. I live, you know, in that myself. And then as writers, if we can’t write about these things, if we can only write about what we know and experience, that would be a very, very narrow world.

Joanna: Very boring!

Sarah: Yes, my world would be very boring.

Joanna: Mine would too.

Sarah: You know, if I can only write about women who are part Choctaw, part white, that’s all I can have in my cast. That would be very strange.

And so I hate that you had that experience, and I’ve known of writers almost being in tears because they want to write Native American characters, but they’re afraid they’ll get it wrong, they’re afraid they’ll be criticized. And honestly, they probably will face that no matter what you do. Just as you said, you research, your husband’s a Jew, you’ve done all of these things, and your story’s not even that, and you still receive criticism.

So you’re going to have that sometimes, but ultimately, for me, I believe that writers should be judged based on the quality of their writing, and not on their race.

So regardless of what their ethnicity is, regardless of what their background or religious beliefs, we should be able to explore all of those in writing, but do it in a respectful, well-researched way. And that’s just my message for writers who want to write about Native Americans.

As a Choctaw, I’m open to that. And I want to teach writers how to do that in the best way they can because I think most writers have a heart for doing it right. I don’t think writers are setting out to be offensive or to be rude or to be hateful or racist. They’re setting out to write a good story. And I want to help writers do that.

Joanna: I agree. I think there is more of an awareness of this now. And when authors do it in a deliberate fashion, they are doing it because they’re trying to do it respectfully. Unless they are not, obviously. There are some people who write things who are not being respectful, but we’re not talking to them.

So you’ve mentioned the wise guide. We’ve mentioned the tomahawk-wielding Indian on a horse.

Are there any other stereotypes that you get really annoyed about and want to question?

Sarah: Oh, there are so many. I actually have a free eBook, 5 Stereotypes to Avoid When Writing about Native Americans. And so I have five of them in there, I have 12 in my course. And I have people who have done a ton of research on American Indians, that are like, I didn’t even know some of these things. And a lot of them people will be familiar with.

And there’s nothing wrong with having the wise guide, I could point that out. If that’s a character in someone’s story, just make sure it’s not stereotypical and they’re put in there specifically for that reason, and that’s the only aspect of the American Indian character that we get to see.

So the other stereotype that I could point out that is not talked about very often, and that’s what I call the historical-only point of view. And that’s where people write about, especially if they’re writing historical fiction, or even fantasy, where they have this perception or this viewpoint that American Indians are in the past. That it’s all about history, and what went on in the past.

And so when they write from that perspective, there’s almost this ending to the character, like their way of life and their people are going to end in the 19th century.

What my perspective is, whenever I’m writing historical fiction, is the people go on, why people go on, and our culture and our history lives on well into the future to my lifetime, and I think continuing on further into the future.

So when writers have that historical-only point of view, there’s just this almost closure of “we’re writing about this people group that no longer exist,” and just having that awareness that native people are still here.

Joanna: That’s so important.

And I mean, you mentioned on your father’s side, so do you identify as mixed race?

Sarah: I am. So my papaw is on my mother’s side, so through my mother is where I get my Choctaw ancestry, and my dad was a Kansas farm boy. And my mother, we have Irish ancestry and French, I mean we have it all mixed back in there. So we are, one of the terms that was used back in the 19th century and 20th century and today, is ‘mixed bloods.’

And that’s what we are, we’re mixed race. And so I write about my Choctaw heritage. I think you were saying, what’s one of the questions I get asked often, one of them is when I tell people I’m Choctaw, they’re like, well, how much?

Joanna: Is that an offensive question?

Sarah: It’s not offensive to me. Some people will take offense to it because no other race is based on blood quantum other than Indians and dogs, is what one professor says. We’re the only ones that get the dipstick.

But what I like to let people know is my fourth-generation grandfather buried his father on the Trail of Tears, and I’m 100% his descendant. That’s how much Choctaw I am.

Joanna: That’s a really interesting question. Like, that’s just not something someone would ask me, even though I have done one of those genetic tests, and I’m like a ridiculous number of different racial backgrounds. I mean, I have something like 12 different racial characteristics. It’s really interesting, that question, there’s so much in there.

Sarah: Yes, there is.

Joanna: Isn’t there? And again, I’m just asking these questions because I want people to feel like it’s okay. Do you look Native American because we’re on audio only? And I feel like that might be something else. When people ask that question, is that because they look at you and think, well, you just look like, I don’t know, the Kansas farm girl?

Sarah: Right, I do. I do look more like the Kansas farm girl. I have the hazel eyes and white skin. You put me next to my brother, who we’re full brother and sister, same mom and dad, and we look completely different. He looks so Choctaw, he’s on the cover of two of my books.

Joanna: That’s brilliant.

Sarah: He has the dark skin. He’s been to Nicaragua, and Mexico, Jamaica, and wherever he’s at people just start speaking to him in their language because I think he’s just part of whatever they are. And he’s like, I’m an American, right? So he has the dark skin, and my mother has the darker skin. And so people were always asking her when she was growing up, like what are you? They didn’t even know. It was like, you’re not Hispanic, you’re not white, what are you? And so I don’t get offended with that.

And it’s really not because of my skin color that people ask me that because they ask my mother that, they’ll ask my brother that, they ask my nephew that, which tickled me because he has the hazel eyes, blonde hair and dark skin. So people are always asking him, “What are you?” And he’s like, “I’m human.“

Joanna: I’m human. That is very good. It’s so interesting, I feel like people always want to put people in boxes. And as writers, we are guilty of this because we put characters in boxes. And we say this needs to be this because of story reason.

So I guess our overarching message is: don’t assume anything, just make someone a well-rounded character in your writing.

They might be part Choctaw, and maybe I imagine some of the people who are in your situation, so whatever that percentage is, don’t identify in that way. Like plenty of people don’t identify with their heritage. So don’t assume things about your characters, but create them in a respectful way and do your research. That’s probably the method.

Sarah: That really is because that’s what we need to do with all of our characters, right? We don’t want them to be one dimensional and they’re just there to serve a specific role in the story. You want them to be a fully fleshed out character.

Joanna: For sure.

Tell us a bit more about your course and where people can find you online.

Sarah: Oh, wonderful. So my course is called Fiction Writing: American Indians. And you can find it at AmericanIndians.FictionCourses.com.

And if you scroll to the bottom of that page is where you can download the free PDF, 5 Stereotypes to Avoid When Writing about Native Americans. For my books, visit ChoctawSpirit.com, that’s my shared site with my mother who does Choctaw beadwork, but you’ll find all of my books on there. And you can find them, of course, on all of the major online platforms. And for my course, Joanna, if it’s alright, I created a coupon code called thecreativepenn for $30 off for anyone who uses that coupon code and enrolls in the course.

Joanna: Brilliant, and is that Penn with a double N?

Sarah: It is.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Sarah. That was great.

Sarah: Oh, I appreciate it, Joanna. And we don’t have a word for goodbye in Choctaw, we say, chi pisa la chike. I will see you again soon.

The post Writing Choctaw Characters And Diversity In Fiction With Sarah Elisabeth Sawyer first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn