To say there are a lot of literary agents out there is an understatement—almost like saying there are a lot of writers looking for an agent (but not quite). The Association of Authors’ Representatives (AAR), a nonprofit membership organization founded in 1991, currently lists more than four hundred agents as members, all of whom meet certain experience requirements and abide by an established code of ethics. Another, more general, online database claims to offer details for nearly a thousand agents of varying levels of expertise and areas of emphasis. The carefully curated and focused database of literary agents at pw.org lists more than a hundred, including contact information, submission guidelines, and client lists.

No, the challenge for writers is not a dearth of agents, but rather picking the right one out of the crowd. (Of course, the same could be said about the challenge for agents.) To help narrow the field, I contacted some hungry agents who I know are eager to receive an e-mail from an as-yet-unknown writer and asked each of them for some basic information about what kind of work they want to read and how to reach them, as well as some not-so-basic information that will help you get to know them a little better. Remember, publishing is a business of relationships. You don’t want to simply fire off an e-mail to any agent you happen to come across. Read carefully. In the following profiles, a dozen agents are dropping some subtle (and not so subtle) hints for you. Have you written a piece of narrative nonfiction that gets to the heart of what it means to live in a specific geographical region? Duvall Osteen might be a great fit. Do you have a novel set in North Carolina? Adam Eaglin could be your man. Are you from Detroit and love music? You may need to look no further than Carrie Howland. Are you a writer of smart horror fiction and just can’t get enough of the work of Joe Hill and Nathan Ballingrud? You should take the time to get to know Renée Zuckerbrot.

These twelve agents all have distinct personalities, aesthetics, work habits, backgrounds, proclivities, and peeves—and so do you. So take your time, do the research, read books by their clients, and listen to what these professionals are saying. One of them might be speaking directly to you.

Danielle Svetcov, Levine Greenberg Rostan Literary Agency

Who she represents: Bridget Quinn (Broad Strokes), Bonnie Tsui (Why We Swim), Nicole Perlroth (This Is How They Tell Me the World Ends), Stephanie Wilbur Ash (The Annie Year), Meg Elison (The Book of the Unnamed Midwife), James Nestor (Deep), Shalane Flanagan and Elyse Kopecky (Run Fast Eat Slow), Eben Weiss (The Ultimate Bicycle Owner’s Manual)

What she wants to read: Biographies and histories in which I can smell the breath and walk in the footsteps of the characters profiled; memoirs and reported narratives braced by vivid scenes and a sense of urgency; humor that can revive a marriage when read before bed; fiction that reads easy but isn’t.

When you should contact her: If your manuscript is the only piece of writing you’ve got to share (you’re not a working journalist, say, or a published author), then your manuscript (if it’s fiction) should be complete before you query. If you are a professional writer with clips galore to share, I still recommend you query when you’ve got a finished manuscript (if fiction), because it leaves no mystery (but it’s up to you). If you’re submitting nonfiction—all writers—then you should have a full proposal to share when you query. Coda: An agent should not be the first person (besides you) to read your manuscript or proposal.

Where she can be reached: e-mail dsvetcov@lgrliterary.com

Why you should want her as your agent: To quote my clients: “relentless,” “wolfish,” “and she always calls you back.”

How she wants to be contacted: Send query letter with attached proposal or sample of fiction (say, twenty-five pages).

Renée Zuckerbrot, Massie & McQuilkin Literary Agents

Who she represents: Dan Chaon (Ill Will), Shannon Leone Fowler (Traveling With Ghosts), Kelly Link (Get in Trouble), Deborah Lutz (The Bronte Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects), Andrew Malan Milward (I Was a Revolutionary), Keith Lee Morris (Travelers Rest), Shawn Vestal (Godforsaken Idaho), M. O. Walsh (My Sunshine Away), Daniel Wallace (Extraordinary Adventures)

What she wants to read: I tend to be seduced by voice, so voice-driven fiction and nonfiction are high on my wish list. I love getting lost in a world that is strikingly different from mine. I have a deep appreciation for storytelling that allows me to see the world anew, or introduces me to a culture or worldview outside my own. I read to be entertained and educated. Writers who approach current events and historical topics with original, provocative ideas will always find readers. I’m also looking for smart horror writers along the lines of Joe Hill and my client Nathan Ballingrud (North American Lake Monsters). There will always be room on my list for popular science—Eric Sanderson’s Mannahatta: A Natural History of New York City is a good example—and pop-culture books like my client Theron Humphrey’s Maddie on Things.

When you should contact her: Please query me when you have a complete manuscript or proposal with a sample chapter. I am also willing to look at a complete short story collection and partial novel, or a complete novel and a partial story collection. For memoirs, I will consider a proposal with a sample chapter or the complete manuscript.

Where she can be reached: e-mail renee@mmqlit.com

Why you should want her as your agent: I am a careful reader who reads on both a micro and macro level. My first job was in editorial—I’m a former Doubleday editor—so it’s all about the writing. I work with my clients on getting their work in the best shape possible before submitting it. That said, my job is not to edit a manuscript so that it conforms to my idea of perfection; rather, it is to edit a work so that editors reading it will be able to envision the book as the writer intends. I need to leave enough room for editors to work with my clients to shape their manuscripts to their shared vision and the publisher’s vision. I’m proud of the fact that the manuscripts I sell never require major editorial overhauls. Also, I value fostering long-term relationships with my writers. Last but not least, I’m enthusiastic about collaborating with my writers and their publishers during the publication of their work. I love helping to generate buzz for my clients by talking up their work to anyone who will listen.

How she wants to be contacted: Please include a description of your work, your writing credentials, a brief bio in the body of an e-mail, along with the first three chapters/stories from your manuscript as a Word document. For nonfiction, you can also send a proposal and sample chapter.

Duvall Osteen, Aragi Inc.

Who she represents: Bethany Ball (What to Do About the Solomons), Elizabeth Poliner (As Close to Us as Breathing), Marjorie Liu (Monstress), Lauren Holmes (Barbara the Slut and Other People), Brooke Barker (Sad Animal Facts), Brad Watson (Miss Jane), Bryce Andrews (Badluck Way: A Year on the Ragged Edge of the West), Wil S. Hylton (Vanished: The Sixty-Year Search for the Missing Men of World War II), Pablo Medina (The Island Kingdom)

What she wants to read: Fiction and narrative nonfiction with a big voice and/or a strong sense of place.

When you should contact her: For fiction I request completed novels or story collections. For narrative nonfiction I’m happy to read a proposal, which should include an overview and at least two finished chapters.

Where she can be reached: e-mail queries@aragi.net; attn: Duvall Osteen

Why you should want her as your agent: We’re a small, selective agency. We keep it that way for a reason. Our authors are never going to be handed off; they can always reach us, no matter how big or small the question, no matter what stage of their career. Every single author at Aragi is of equal importance.

How she wants to be contacted: Please send your query via e-mail, which should include a synopsis of the book and your bio.

Jeff Kleinman, Folio Literary Management

Who he represents: Garth Stein (The Art of Racing in the Rain), Elizabeth Letts (The Eighty-Dollar Champion), Eowyn Ivey (The Snow Child), Jacquelyn Mitchard (Two If by Sea), Charles J. Shields (Mockingbird), Karen Dionne (The Marsh King’s Daughter), Benjamin Ludwig (Ginny Moon), Val Emmich (The Reminders), Kathy McKeon (Jackie’s Girl)

What he wants to read: I focus on book-club/literary fiction and narrative nonfiction—especially those projects that I feel can make a difference either to me personally or to the world. I love unique voices, magnificently strong characters, unusual premises, and books that offer some new perspective on something I thought I already knew something about or never even dreamed existed. I’m always interested in learning and love when someone can teach me something organically so it doesn’t feel like I’m even learning. I’m particularly looking for voice-driven fiction as well as very well-written thrillers and psychological suspense novels; or novels with a great, quirky, fun voice. I love narrative nonfiction and memoir and have sold projects in a wide variety of subjects, including art, history, animals, military, and many other genres.

When you should contact him: Fiction writers, when you’ve finished your entire novel, had it read by several readers, edited and reedited it, and feel like it’s now absolutely as strong as you can possibly make it, write me a letter and tell me about it. Nonfiction writers, when you’ve written a book proposal, paying particular attention to the sample chapter(s)/excerpts and marketing materials, write me a letter.

Where he can be reached: E-mail jeff@foliolit.com, but please consult the Folio website (foliolit.com) before you fire off an e-mail. No phone calls or hard copies, please.

Why you should want him as your agent: I’m very hands-on and love the editing-collaborating process—brainstorming plots, rejiggering motivations, tweaking backstory. It’s really satisfying and invigorating to be part of the creative process. I also love being part of the publication process, too—coming up with marketing ideas, discussing PR strategies, revising flap copy, reading/editing short promotional materials, and so forth. I do best working with authors who see their agent as a partner in the book publishing process: I’m not a guy who rubber-stamps a manuscript and just forwards it to the editor; and I don’t just disappear once the book has been sold. As one author told me recently, “I was just saying that what you do for me is not normal. I don’t know of a single other agent who works so hard to make sure his clients look good—and I know a lot of agents!”

How he wants to be contacted: For fiction, a query letter plus the first page of your manuscript; for nonfiction, a query letter plus a proposal overview and/or first page of a sample excerpt.

Eleanor Jackson, Dunow, Carlson & Lerner

Who she represents: David Wroblewski (The Story of Edgar Sawtelle), Susie Steiner (Missing, Presumed), T. Geronimo Johnson (Welcome to Braggsville), Aline Ohanesian (Orhan’s Inheritance), Susan Straight (Between Heaven and Here), Michael Lemonick (The Perpetual Now)

What she wants to read: I believe a good book should wake you up by taking you out of your life and immersing you in someone else’s. So I want to read books with deeply imagined worlds, by writers who are not afraid to take risks with their work.

When you should contact her: Fiction writers, I want you to contact me when you have a full draft of your novel. I sell a lot of nonfiction on proposal, so I’m happy to look at those projects a bit earlier. If I’m considering nonfiction on proposal, I’d like to see one or two sample chapters. In general, I think the best moment for writers to contact an agent is when they have done everything they possibly can on their own.

Where she can be reached: Dunow, Carlson & Lerner Literary Agency; 27 West 20th Street, Suite 1107; New York, NY 10011; e-mail eleanor@dclagency.com

Why you should want her as your agent: I consider my clients my friends. They all have my cell-phone number and are free to use it. My list is intentionally small, so I can give every project the attention it deserves. I also like to think long-term, about how to build a career as well as sell individual books.

How she wants to be contacted: Please send me a one- to two-page query letter with a summary of your work and an author bio. If you have a proposal, please attach it to your query. If you are working on a novel, please attach the first ten to twenty pages to give me a sense of your writing.

Allison Hunter, Janklow & Nesbit Associates

Who she represents: Katie Heaney (Never Have I Ever), Arianna Rebolini (Public Relations), Swan Huntley (We Could Be Beautiful), Anna Pitoniak (The Futures), Anne Helen Petersen (Too Fat, Too Slutty, Too Loud), Christina Kelly (Good Karma), Victoria James (Drink Pink), Kelsey Miller (Big Girl), Jen Chaney (As If!), Emilie Wapnick (How to Be Everything), Dvora Meyers (The End of the Perfect 10), Eliot Nelson (The Beltway Bible), Megan Mulry (A Royal Pain)

What she wants to read: Literary and commercial fiction, especially upmarket and women’s fiction, as well as select memoir, narrative nonfiction, cultural studies, and pop culture. I’m especially looking for funny female writers, great love stories, campus novels, beach reads, family epics, and nonfiction projects that speak to the current cultural climate.

When you should contact her: Fiction writers, please wait until you have a complete, polished manuscript. Nonfiction writers, you should have a fully fleshed out idea and ideally a full book proposal.

Where she can be reached: e-mail ahunter@janklow.com

Why you should want her as your agent: I like to think that I offer my authors the best of both worlds—the resources of a large, world-class agency but with a great deal of personal attention. I am a fast and voracious reader and feel that it is my duty to read widely in the genres I’m representing, to fully understand the market. I pride myself on my close working and personal relationships with editors at every publishing house, as well as my connections with the greater literary community in New York City.

How she wants to be contacted: Please send me a query and approximately ten to fifteen pages of your manuscript or proposal.

Carrie Howland, Empire Literary

Who she represents: Kaitlyn Greenidge (We Love You, Charlie Freeman), Carmiel Banasky (The Suicide of Claire Bishop), Melissa Gorzelanczyk (Arrows), Sarah Prager (Queer, There, and Everywhere), Jason Tougaw (The One You Get)

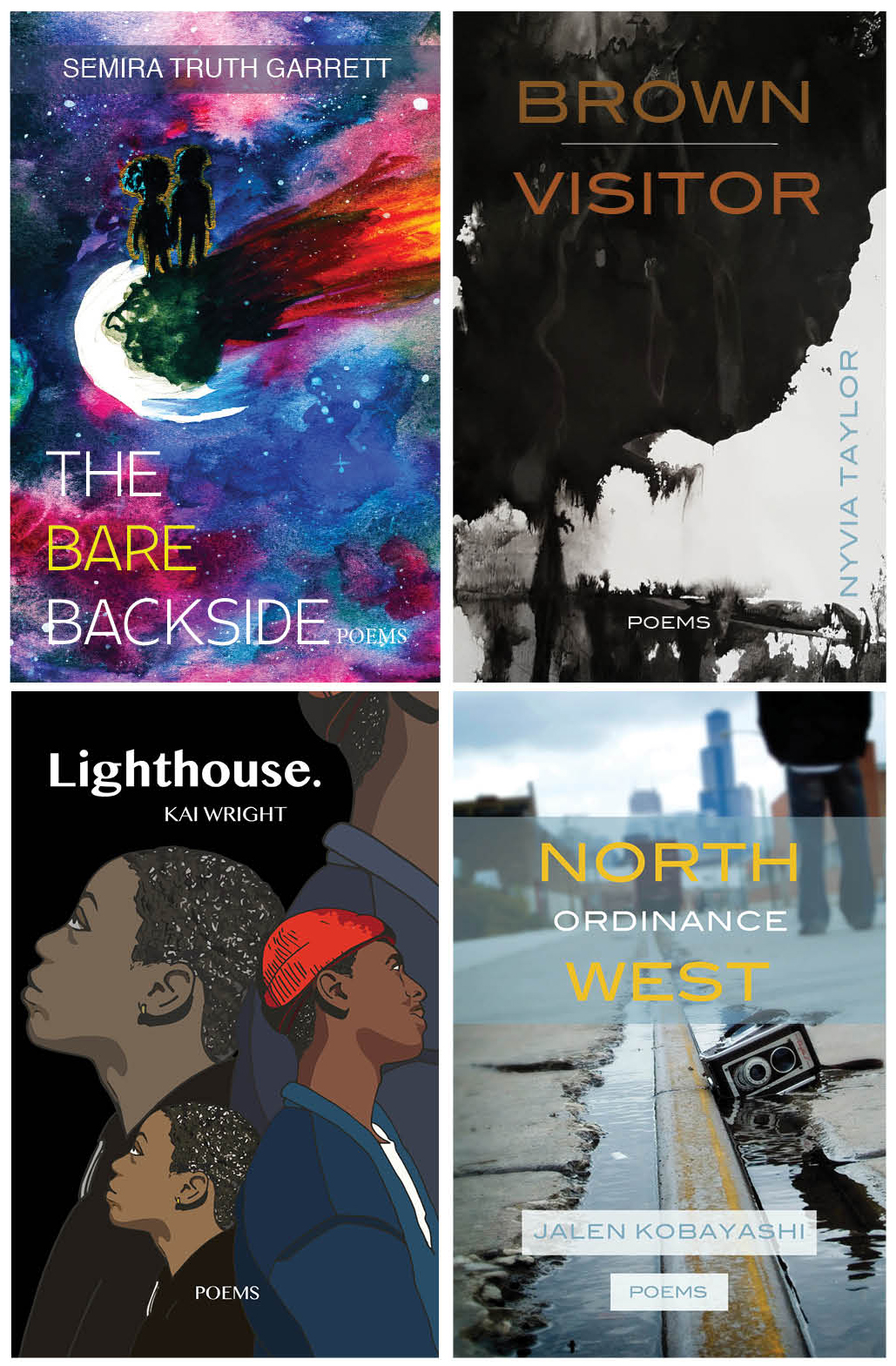

What she wants to read: I’m actively seeking adult-fiction writers, both literary and upmarket. My background is in poetry and literary fiction, so beautiful language is one of the first things I look for in any project. Equally important are a strong voice and great story, which I’m looking for across genres. I would love to see a literary thriller, whether adult or young adult, come across my desk. For children’s books, I love voice-driven, contemporary fiction that isn’t afraid to tackle tough issues. I adore a middle-grade adventure story but am also taken by one that might deal with the loss of a sibling, for example, or a serious issue at school or with a friend. For nonfiction, I’m a music fanatic, and as such I’m always looking for great books on movements, culture, musicians themselves, or simply how we as a society respond to, and are affected by, the music around us. I’m a Detroit-area native, so I’d also love submissions for books that deal with the city itself, or cities like it, the politics surrounding them, and stories of people who live there. In addition to poetry, I have a strong background in public policy, so I’m incredibly interested in books that deal with politics, education, or other societal issues. Finally, I love all things pop culture, so I will never say no to a proposal about anything from “why we’re a Bachelor-obsessed nation” to “why we can’t ever seem to get enough of Gilmore Girls.”

When you should contact her: For fiction, a project should truly be finished before I see it. I recommend you have a not only complete but also well-edited manuscript before sending to me, or any agent. For nonfiction, a proposal is perfect.

Where she can be reached: e-mail carrie@empireliterary.com

Why you should want her as your agent: After nearly twelve years as an agent, representing award-winning authors, I’ve developed a hands-on approach to launching the careers of debut novelists. I’m a very editorial agent and love collaborating with my clients. Whether that’s idea development, manuscript feedback, assisting with publicity, social media, or marketing, I really do consider myself a full-service partner for my authors. I absolutely love what I do; I live and breathe for my clients and work tirelessly to promote their work and careers. Beyond that, while I’ve been a New Yorker for over a decade, I’m a Midwestern girl at heart, so you’ll find not only an advocate, but a friend in me as your agent. This can be a tough business, and I like to remind my clients why we all chose this profession in the first place: because we’re passionate about the written word.

How she wants to be contacted: Please send your query letter and first twenty pages (for fiction) or proposal (for nonfiction) as a Word document to carrie@empireliterary.com.

Ross Harris, Stuart Krichevsky Literary Agency

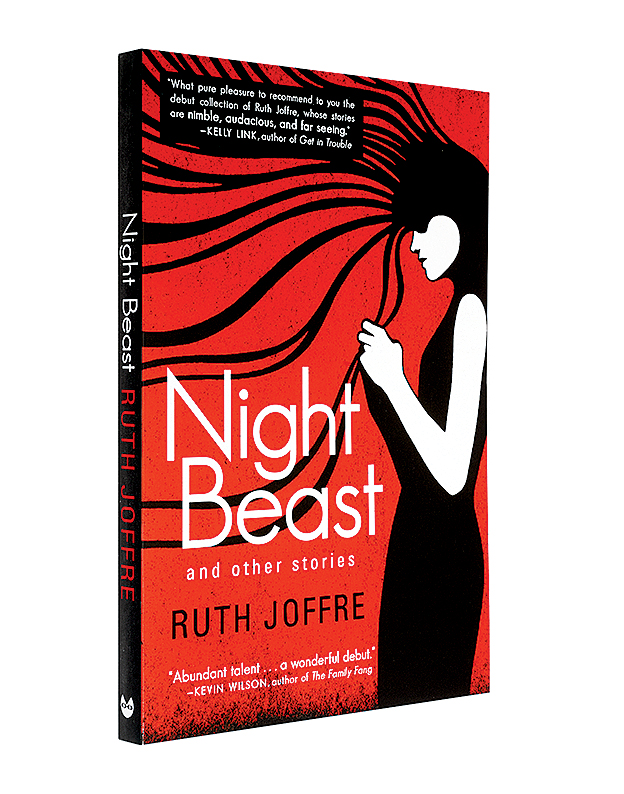

Who he represents: Isaac Oliver (Intimacy Idiot), Charlyne Yi (Oh the Moon: Stories From the Tortured Mind of Charlyne Yi), Rachel Lindsay, Manoush Zomorodi (Bored and Brilliant: How Spacing Out Can Unlock Your Most Productive and Creative Self), A. Brad Schwartz (Broadcast Hysteria: Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds and the Art of Fake News), Rebekah Frumkin (The Comedown), Ruth Joffre (Night Beast and Other Stories)

What he wants to read: My taste tends to lean toward the literary, but as long as the plot surprises and entertains, I’ll be won over. I love to find new, unpredictable stories—I think every agent will tell you that—but I particularly enjoy the feeling, the unease, the excitement that creeps in when I honestly don’t know what’ll happen next. When I finish a book (or proposal), the lasting feeling of wonderment is what I’m after.

When you should contact him: You should write to me (and, yes, please do!) when you feel comfortable sharing your work. I tell writers that the right time to share your work with an agent is when you feel confident that it’ll speak for itself—without you having to be in the room. If you’re going to want to be over my shoulder saying, “Well, this part will be fixed…” or “I intend to make this part a little clearer…,” you aren’t ready to share the work, which is completely fine. Many writers make the mistake of looking for an agent too soon. An agent’s primary job is to sell your work, so if you don’t have anything yet to sell…wait until you do. You get one first impression. Make it count.

Where he can be reached: My inbox is always open to new and prospective clients: rh@skagency.com.

Why you should want him as your agent: I’m fun, I mean business, I care deeply about seeing each and every client succeed in her or his own way. When I work with any writer, regardless of genre or style, it’s a very personalized relationship.

How he wants to be contacted: A partial manuscript, a proposal, or full manuscript. The work doesn’t have to be 100 percent polished, but remember that I’m going to be considering its salability, not potential salability. Just make sure you’re ready (and feel confident) to send. If you’re excited to share your work with me, I’ll be excited to read it.

Caroline Eisenmann, Frances Goldin Literary Agency

Who she represents: Meghan Flaherty (Tango Lessons), Brandon Hobson (Where the Dead Sit Talking)

What she wants to read: In almost any genre, I’m attracted to great prose and a strong sense of emotional intelligence on the page. For upmarket and literary fiction, I tend to be particularly drawn to relationship-driven novels, stories about obsession, and work that grapples with intimacy and its discontents. With nonfiction, I’m very interested in deeply reported narratives and stories that take the reader into the heart of a subculture as well as idea books with a surprising or unusual central argument.

When you should contact her: I’d like to see your work when you feel you’ve taken it as far as you can by yourself. With a novel, this will almost always mean an edited full manuscript; in nonfiction, I’d generally want to read at least the fundamental elements of a proposal (outline, sample pages, etc.).

Where she can be reached: It’s best to get in touch by e-mail at ce@goldinlit.com

Why you should want her as your agent: I do a lot of editorial work with my clients, generally from the ground level of a project. That can mean brainstorming about the concept behind nonfiction or coming up with plot solutions in fiction, but my goal is always to help authors reach the best possible version of their book before submission. I’m also a clear communicator who’s constantly thinking about what my clients want and need, and I will do everything possible to make those goals happen. I worked in marketing and digital publishing before coming to agenting, which gives me extra insight into how to position my clients in an evolving landscape.

How she wants to be contacted: Please send a query. If the work is fiction or completed nonfiction, include the first ten pages in the body of the e-mail.

Adam Eaglin, Cheney Associates, LLC

Who he represents: Lawrence Osborne (Hunters in the Dark), Jennine Capó Crucet (Make Your Home Among Strangers), Ron Rash (The Risen), Lisa Servon (The Unbanking of America: How the Middle Class Survives), David Treuer (Prudence), Devin Leonard (Neither Snow nor Rain: A History of the United States Postal Service), Leah Vincent (Cut Me Loose: Sin and Salvation After My Ultra-Orthodox Girlhood), Diksha Basu (The Windfall)

What he wants to read: Debut literary and upmarket fiction; narrative nonfiction and memoir; journalists and academics writing new takes on culture, politics, and current events. Regardless of genre, I’m always interested in diverse voices and underrepresented perspectives, and as a native North Carolinian I am partial to great fiction set in the South.

When you should contact him: For fiction, it’s usually best to be in touch when you have a finished manuscript to share. For nonfiction, a draft of a proposal.

Where he can be reached: e-mail adam@cheneyliterary.com

Why you should want him as your agent: I try to keep a small, selective list and only take on projects I really believe in, which enables me to be a hands-on and passionate advocate for each of my writers. This includes in-depth editorial work, working strategically to find the best publishing deals, and shepherding an author through all aspects of the publication process, including publicity and marketing. My goal is always to help each of my author’s books make as big an impact as possible and to build careers over time.

How he wants to be contacted: A query by e-mail with a full manuscript (for fiction) or a proposal (nonfiction).

Amelia Atlas, ICM Partners

Who she represents: Caite Dolan-Leach (Dead Letters), Mark O’Connell (To Be a Machine), Matt Gallagher (Youngblood), Joy Williams (Ninety-Nine Stories of God)

What she wants to read: I’m looking for books—whether fiction or nonfiction—that feel engaged with the larger world. That can mean having a big new idea, taking me to a place or a part of history that I haven’t seen, or simply having a kind of inquisitive spirit. I’m looking for writing that comes from a place of urgency.

When you should contact her: Ideally I’d like to hear from writers who have a finished manuscript or proposal ready for review. At the very least it should feel like you’ve really pushed the project as far as you can without outside eyes and feedback.

Where she can be reached: e-mail aatlas@icmpartners.com

Why you should want her as your agent: The projects I look for are the kind of things I know I’m going to want to be in the trenches fighting for in the years to come (publishing is a slow business), and I think that shows in how I work with my clients—whether it’s reading multiple drafts, batting ideas around, or shepherding them through the publishing process. I like to be pretty hands-on, especially in the early, developmental stages: It’s exciting to watch something become the book we know it should be.

How she wants to be contacted: A query letter plus the first ten pages pasted into the body of an e-mail.

Julie Barer, The Book Group

Who she represents: Joshua Ferris (To Rise Again at a Decent Hour), Bret Anthony Johnston (Remember Me Like This), Lily King (Euphoria), Celeste Ng (Everything I Never Told You), Cristina Henriquez (The Book of Unknown Americans), Helen Simonson (Major Pettigrew’s Last Stand), Mia Alvar (In the Country), Madeline Miller (The Song of Achilles), Alice Sebold (Lucky), Kathleen Kent (The Heretic’s Daughter), Nicole Dennis-Benn (Here Comes the Sun), Megan Mayhew Bergman (Almost Famous Women), Paula McLain (The Paris Wife), Kevin Wilson (The Family Fang), Charles Yu (How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe)

What she wants to read: My list is predominantly fiction, and I am particularly interested in representing diverse voices and perspectives from around the world. I’m always looking to learn something new from the fiction I read and to be taken somewhere I’ve never been before. I’m drawn to original voices, or retellings of stories we’ve heard before in new and innovative ways. I need to feel emotionally connected to the characters, and as obvious as it sounds, I need a real plot. More than anything, though, I just want to fall in love. I want to miss my subway stop because I can’t stop reading. I want to completely disappear into the world of the novel. I want to turn the last page and immediately feel the need to tell everyone I know about it.

When you should contact her: In general I think it’s best, when writing fiction, if you have a complete and polished manuscript. That means you’ve taken the time to self-edit and even stepped away from the project for some time so you know that you’ve really put everything into it that you can. If it’s nonfiction, then a proposal with forty to fifty pages of material is usually enough.

Where she can be reached: The Book Group, c/o Julie Barer; 20 West 20th Street, Suite 601; New York, NY 10011; thebookgroup.com; e-mail submissions@thebookgroup.com

Why you should want her as your agent: At the Book Group we believe in a very hands-on approach at every stage of the publication process. I love to edit, and I bring a strong editorial eye and passionate commitment to each project, making sure I’ve done all I can do to help authors realize their vision and address any issues before we submit to publishers. I’m extremely selective in taking on new projects, which ensures that I’m able to give my clients the time and attention they need. I’m also committed to helping my clients establish and navigate their careers across many years and many books, so I like to be involved in everything from helping write jacket copy to developing a social media presence, pitching magazine ideas, and submitting short stories to brainstorming for the book’s marketing campaign and beyond. We are right there with you every step of the way, and in addition to the U.S. market, we’re thinking about international sales, film, television and audio, and also what your next project should be. This long-term, big-picture perspective and involvement is one of the most interesting parts of my job.

How she wants to be contacted: Please submit a query letter along with ten sample pages with “Julie Barer” in the subject line to submissions@thebookgroup.com. Please do not include any attachments.

Kevin Larimer is the editor in chief of Poets & Writers, Inc.

What were some of your best-selling

What were some of your best-selling

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?