Writing a first draft is only the initial step in the journey to creating a novel. The next step is editing, and in this interview, Kris Spisak talks about the different kinds of editing, as well as tips for your self-editing process. Plus, I share my insights from my latest edit on Map of the Impossible.

In the introduction, Apple discontinues iBooks Author [MacRumors] but remember, they have the new Authors.Apple.com, a portal to all things publishing on Apple; #publishingpaidme trended on Twitter and the amounts are listed in this spreadsheet; Written Word Media survey on How Readers Pick What to Read Next; Everything you need to know about pre-orders on the 6-Figure Author Podcast.

Today’s show is sponsored by ProWritingAid, writing and editing software that goes way beyond just grammar and typo checking. With its detailed reports on how to improve your writing and integration with Scrivener, ProWritingAid will help you improve your book before you send it to an editor, agent or publisher. Check it out for free or get 25% off the premium edition at www.ProWritingAid.com/joanna

Today’s show is sponsored by ProWritingAid, writing and editing software that goes way beyond just grammar and typo checking. With its detailed reports on how to improve your writing and integration with Scrivener, ProWritingAid will help you improve your book before you send it to an editor, agent or publisher. Check it out for free or get 25% off the premium edition at www.ProWritingAid.com/joanna

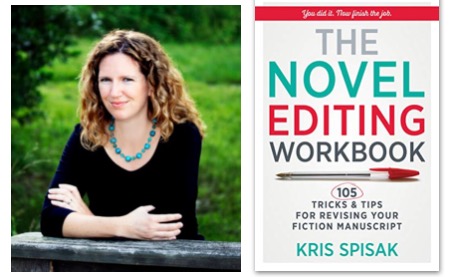

Kris Spisak is a nonfiction author, an editor, podcaster, and international speaker. Today, we’re talking about The Novel Editing Workbook, 105 Tricks & Tips for Revising Your Fiction Manuscript.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- What editing really is and the three levels of editing

- Tips for making sure your story hangs together properly

- Tools for organizing your story

- Writing scenes that are page-turners

- Tips for writing compelling characters

- Adding sensory detail to pull readers into the book

- Tips for writing effective dialogue

- Common writing issues to watch out for

- The editing an author can do themselves, and when they need professional assistance

You can find Kris Spisak at Kris-Spisak.com and on Twitter @KrisSpisak

If you need more help, you can find my list of editors and proofreaders here, and also my tutorial on how to find and work with a professional editor here.

Transcript of Interview with Kris Spisak

Joanna: Kris Spisak is a nonfiction author, an editor, podcaster, and international speaker. Today, we’re talking about The Novel Editing Workbook, 105 Tricks & Tips for Revising Your Fiction Manuscript. Welcome, Kris.

Kris: Hi, Joanna. Great to be here.

Joanna: Thanks for coming on the show. I have a print copy of your workbook, I bought it in print because I thought it was so good.

Kris: Oh, thank you so much. It was so much fun to pull together. I had been teaching those materials for so many years and I had been working with my editing clients for so many years saying the same things over and over. I realized there were some universal truths about editing that the world didn’t seem to know, so it was time to write that book.

Joanna: And a great reason to write a nonfiction book, to be honest, like you already have an audience and this just helps you.

Before we get into that, tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and editing.

Kris: I’m one of those people who has been writing since I can remember, since I was a little kid, but I had been teaching university writing courses. And just loving the joy of enjoying the power of the written word, connecting with different audiences in different ways, whether you’re storytelling, whether you are writing manifestos, or theses, or whatever it happens to be.

While I was teaching, I kept getting approached on the side to write, I don’t know, CEO blogs to go straight for them. Getting to write product descriptions on Amazon, getting to write…somebody who I knew who had a novel who needed some help with that.

So I kept getting approached on the side because people knew I was really just obsessed with the power of language. And I could really dive into the nitty-gritty of not only grammar but the approach of how you put your words together for the most powerful effect.

I was doing that for a while on the side while I was teaching and I had this moment of realization saying, ‘Wait a second, I am having so much fun in the classroom but I am having so much more fun getting to work in all of these different spaces just with the power of language.’ So, slowly I kind of trickled my way out of the classroom and into my own writing and editing business. And haven’t looked back since, it’s been 10 years now.

Joanna: Oh, fantastic. We started about the same time then I guess.

Kris: Yes. I’m a long-time listener too, I remember listening to you back in your Australia days.

Joanna: Ah, well, there we go. One of the early crowd, that’s fantastic. Let’s start with some definitions around what editing is. Because many new writers think it’s about typos and grammar.

What is editing really?

Kris: I’m so happy you asked this question because so often, when I say that I’m an editor, everyone starts thinking about the grammar police and we start getting into very heated debates about Oxford commas or no Oxford commas. And yes, that is a piece of editing, but that proofreading, that final line is really the absolute last piece of editing.

When you’re talking about editing, I like to look at it in terms of three different levels. You have your macro edit where you’re really looking at your entire story structure. Does your entire plots make sense? Does your story begin in the correct place? Does it end in the right place? Are your characters fleshed out as much as they need to be? And yes, I said fleshed out, not flushed out, that’s an entirely different conversation!

Then you have your big edit, then you have your micro edit where you’re really looking at your sentence level, looking at your word choice, looking at your sentence structure, looking at how you’re distinguishing your characters’ dialogue, and how that’s separate from each other.

All of those little pieces, sentence by sentence. And not until you’ve gone through the entire macro edit process, the entire micro edit process, then you can get down to commas and spelling and typos and that type of thing. But so often when someone hits the end on their first draft of their manuscript, they are so proud of themselves. And they should be, they should throw some confetti in the air and celebrate and high-five their nearest friends and whatever else is going on there, but you don’t just jump into Page 1, Sentence 1 grammar edit. That is the final stage.

Joanna: I agree. I’m actually editing right now my book, Map of the Impossible, and I’m doing that first macro edit, that story structure. And of course, I have a process because I’ve been doing it a while. For people who might just be starting out with that first macro edit, how do they deconstruct that plot?

How do writers examine the story structure to make sure it hangs together properly?

Kris: Well, what I always like to say is, ‘What is the one big problem of your book?’ Now, I’m not saying, ‘What’s wrong with your book?’ I’m saying, ‘what is your protagonist going after? What are they looking for? What are they questing after?’

If you can figure out what that one big question is, then you can have your little roadmap for deconstructing your entire project.

Now, of course, there are always plots and subplots, and you can have all sorts of questions going on within a book, but having your one major problem that carries your book from Page 1 to the final page allows you to look at every single scene within that book, every single chapter, every single page, and saying, ‘Is this on target or am I getting really excited about this emotional moment that perhaps has nothing to do with my actual plot? Am I getting really excited about this historical-fiction research that I did in the process? And you know what, maybe that sniper that I go on about for 70 pages really has no point in this romance,’ or whatever it happens to be.

If you always return to that question of, ‘What is the problem of a story and is this scene related to that problem?’ you could often figure out where you start wandering away from your core story.

Joanna: What are some of the tools that might help? For example, I do some reverse outlining because I’m a discovery writer, I just make it up as I go along. And then, when I’m doing this kind of editing, I will write a couple of lines about each chapter so I know what’s happening. And then, sometimes I have to move things around because, you know, one scene is at night and the next one’s in the middle of the day and it just didn’t work together.

What are some of the tools for organizing that story?

Kris: People can do this in so many different ways and there are so many fabulous apps from Scrivener to so many others for organizing and giving yourself a brief little snapshot of every little scene or every little chapter. Sometimes you can even just write it all out on note cards.

I like, for us, especially the discovery writers, doing that reverse outline of your book, doing it where perhaps you’ll have everything written out. And then, you go through your entire book not looking at commas, not looking at word choice, but just writing down what is the point of the scene, why is it there, who meets who, where do they go, what are they trying to achieve, and just writing a sentence or two for every single scene. And then, putting it all out.

Again, this can be done in Scrivener, this can be done on index cards that you roll across your office floor, and then just looking, ‘Do all of these things make sense next to each other? Are they all related?’

By doing that reverse-outline process, you can suddenly realize that that scene that you might love so much, it doesn’t actually fit the whole…and you have a chance to actually look at it all from that bird’s-eye view.

Because really, when you’re in the weeds of your book, you can get lost really quickly because you know how much you love your story, you know those characters so well, you know what your plot is doing. But a reader can get lost and you never want to have your reader lost or confused about why something is happening. That reverse outline can kind of keep you on track.

Joanna: And make you realize what you’re missing. How on Earth did that person get from there to there?

Kris: And it’s so funny because we all do it, especially those of us who are discovery writers, I’m the same way, that, all of a sudden, you get passionate about this moment and your characters start running. And then, you’re chasing your characters as you’re typing, and that is sometimes the most fun part of the process. But then you have to realize, that chase could’ve been brilliant or that chase might’ve taken you a little bit off-track, you need to pull it back a little bit.

Joanna: We’ve mentioned scenes there, but one of the other things I do, at this stage of the edit, is chop up my scenes into chapters so that my chapter will have more of a want-to-turn-the-page ending. When I write my scenes, often it feels like a complete scene. But if I ended it there, no one would turn the page necessarily.

What do you think about chopping scenes into chapters so they are page-turners?

Kris: Absolutely. But I mean, whether you’re writing thrillers or absolutely anything, you, as an author, have a goal to get your reader to turn the page. Why else are we doing this if not to have the readers continue to read our books?

Your goal is to finish every single chapter, every single page really, every single ending of a scene is to figure out a moment to close the moment but have your reader begging for more and having new questions arising, new concerns, new emotions evoked so that they are concerned about what will happen next.

If you tie up anything through the course of your book too neatly with a bow, it’s like, ‘Oh. Well, that’s that. It’s definitely time for bed, it’s definitely time to put down that book,’ you never want to give your reader an invitation to put down your book.

Joanna: No, open questions, as you mentioned, that is definitely the way for it. But if you close one, you have to open something else.

Kris: Exactly.

Joanna: So, let’s talk about characters.

When we’re doing this first macro, how do we know whether we’ve done a good enough job or our characters? And what are some ideas for strengthening them?

Kris: Self-editing can be so tricky. And when I say, ‘Self-editing,’ I mean editing yourself. It can be so tricky because, when you’re writing, you probably see this character in your head, you are watching them move. They are alive.

But translating what is going on in your brain through your fingertips to your keyboard doesn’t always work as vividly as we think that we’re actually doing it. So what I like to say is people are incredibly different. Everyone walks down the street in a different way. The way I sit in a chair and the way you sit in a chair is probably remarkably different just because we are two different people.

Focusing on mannerisms, and body language, and especially emotions are something that I really tell people to pay attention to. Because think about the way you get excited, how your face looks, how your body moves, how your fingers might move. Every single part of you reacts to excitement in a different way than someone else does. Every single person reacts to anger or sadness or depression in a different way physically.

If you know a person really well, you can understand that they’re happy without them holding up a sign and saying, ‘Hey, you know what, I’m happy right now,’ you know them because you understand them and how they move and act and enter a room. You understand it.

That’s your goal as a writer is how do you get your reader to understand your characters so well that, the second they walk into that room, just by the way they’re holding themselves, the way they are kicking that rock down the street, the way they are scratching their arm, the way they are pushing their hair in front of their eyes, every single person should have little tells, little emotional tells that let you get to know them better so you never have to say a single emotion on the page, that every single one of them is transparent. And it’s different for every character. You can’t have the same smiley person for every single character.

Joanna: I think it’s also searching your manuscript for evidence that you’re doing that wrong. So feeling, the word feeling, you know, ‘Morgan was feeling something.’

You have to describe it in a different way. Showing, not telling.

Kris: Exactly. I recommend that all writers create a little spreadsheet for themselves. Or if the word spreadsheet just scared half of your listeners, I’ll say it this way, make a little list of words that are your cheat words. They’re absolutely fine in the first draft of a novel but, in your later drafts, look at the word ‘Realize,’ search for ‘realize’ through your manuscript.

Because you know what? You shouldn’t be telling your readers about realization. Your reader should be living through those realizations at the same time as your characters and experiencing it with them. Look for that word feeling, like you just said.

There are so many other examples of that of…that’s kind of just lazy writing. It’s fine for a first draft, it helps you get that story out, but later, this is where you do the fine-tuning of making your characters alive, making those emotions real, making all of those moments a journey for the reader as much of a journey for the characters.

Joanna: It’s great we’re having this conversation now because I’m literally in this edit and I’ve become aware, you become more aware of the things you do regularly. The other thing I’ve been doing is adding in smell because I’m a very visual writer. So I describe scenes, I describe the sense of place, I think that’s one of my strengths. But I completely leave out the way anything smells. And obviously smell is not an every-page thing.

How do we include sensory detail?

Kris: I’m so happy you asked this question because it’s true. To be vivid in our description, and we can talk about the balance of description versus other story elements in a moment, but to be vivid in your description is really what brings your book alive for your readers.

I always like to say, it’s like having a movie screen where you see things happening but you don’t hear it, but you don’t experience it. If you just rely on the visual sense, you’re only showing part of the movie, it does not come alive that way. You have five senses as a person. So allow all of those senses to come into a story.

My one other little cheat-sheet moment here that I always like to tell my editing clients and anybody I talk to is, for some reason, we are always inclined to introduce those sensory details as, ‘She saw,’ ‘he heard,’ ‘it smelled like.’ There is no reason that you need to have those couple words using, ‘She saw,’ ‘he saw,’ or, ‘he smelled,’ ‘it looked like,’ whatever it is.

Avoid that sensory verb. Because what is that bringing attention to? That’s bringing attention to the character who is experiencing whatever you’re describing. Just get straight to the description, cut out the, ‘She saw the tall building that was taller than anything she’d ever seen in her life,’ forget the, ‘she saw,’ just, ‘that building was taller than anything she’d ever seen in her life.’

There are all sorts of little ways that you can tighten your writing and make it come alive for your writers. And sensory details and using all of your senses are powerful but make sure that you’re doing so even more powerfully by cutting those sensory introductions.

Joanna: That’s such a good tip. And it’s one of those, again, new-writer things that you notice later on that you can’t see it in your own writing at the beginning. And we’ll come back to why editors are so useful.

You did mention there description versus other story elements, so you’re going to have to tell us about that now.

Kris: Yes, of course. Oh, I could just talk on this all day.

When you’re looking at that macro edit, again, this is that big picture edit, we’re not worrying about those Oxford commas or no Oxford commas yet. One of the big things to worry about is your balance of story elements. Because I think every writer has a favorite piece of the process.

Maybe you’re a master of dialogue, maybe you are a poet when it comes to your description, maybe you love action scenes and these one after another staccato sentences that really just make your pacing just speed by. But any story has to have a balance of all of these things.

If it’s a screenplay, you can get away if it’s all dialogue all the time, but if you have all dialogue all the time in a novel, again, that’s where we go back to that movie metaphor, that’s just dialogue on a blank movie screen. We can’t see the characters, we can’t see the movement, we can’t see where we are in this moment, there’s no atmosphere.

You have to make sure you balance that description and that action and that dialogue and any other narration that you might have going on. If you just have one element for any duration of time, you are cheating as a writer, you need to make sure you’re balancing it. Because really, that weaving of all of those different story elements is what makes a story come alive and be so vivid in a reader’s imagination.

Joanna: And you can almost see that on a page, can’t you, because dialogue is often a shorter sentence and if you see a page that is dense text, as a novel, then something is possibly wrong.

Kris: Exactly. We live in a moment where we don’t all have so many hours per day to spend on a book, we live in a fast-paced world. So, if you have this one beautiful page that is one entire paragraph of prose, it might be gorgeous but readers just simply don’t have the attention span for it, you need to mix it up and just make it all come alive for someone.

What I like to tell people is to look at any given 10 pages of your book. And when I say, ‘Look at your 10 pages,’ I am actually going to say, ‘don’t look at your first 10 pages,’ because you know what you edit the heck out of? You edit the heck out of your first 10 pages because that’s where you always get so excited about the editing process.

Choose 10 pages in the absolute middle of your manuscript and look at those 10 pages and grab one highlighter for every time there’s dialogue, grab one highlighter for a different color for every time there’s description, one for action or some sort of actual movement, and one for kind of the calmer narration or background or thinking, or whatever else is going on there, and highlight 10 pages.

And you can do this on the screen, you don’t have to waste paper, or you can be someone who prints it out if that’s what works for you.

Examine your writing because then you will notice, just in the middle of your story when you’re not aware of what you happen to be doing, that you probably favor one over the others. Or maybe you’re missing one story element completely that you need to integrate a little bit better. It’s a really great exercise for anybody, no matter where they happen to be in the writing career.

Joanna: Absolutely. And you mentioned action there. I think sometimes people think action means like a fight scene, but with dialogue, often it’s not, ‘Hello, Morgan said,’ it’s, ‘Morgan entered the room,’ and, ‘hello,’ or, ‘hello, Morgan entered the room,’ or some kind of movement as well, instead of dialogue tags. What are your thoughts on that?

I feel like, again, some writers will always be, ‘He said,’ ‘she said,’ or whoever said, as opposed to you having movement.

Kris: Right. I challenge, again, I have so many challenges that I like to give people when it comes to their writing, when it comes to dialogue tags, I like to challenge people to, ‘How many can you cut but still have an entire idea of what is going on in a scene?’

If you took away every single he-said she-said on the page, how could you still convey who is speaking and how they’re speaking and the emotions of that moment? And the answer of course, hint, is not to add their names into dialogue because that’s another faux pas that happens in early writers is that they have characters talking to each other and, ‘Joanna,’ they are talking about something and, ‘Joanna, did you know this?’ and, ‘oh my goodness, Joanna, I just thought of this other idea. Oh my goodness.’

It’s hilarious and it’s one of those things that we don’t realize we do it. And every early writer does do it because they realize, ‘Hey, I’m going to make this conversation more realistic.’ And people use names but they don’t use names as frequently as sometimes appear on the page.

But what I like to do to challenge people to get rid of those dialog tags is to think about, ‘Okay, what’s going on in this moment?’ Maybe, as they are having this conversation, they are cooking together and, as they’re doing that, Joanna picked up the ladle. And then, Chris pulled the Parmesan cheese out of the refrigerator.

You can just have little actions, it doesn’t have to be a sword fight or fists being thrown to have action that can complement the dialogue, to give your readers a hint of who is speaking and the mood of the room. And again, this is a great place to think about description because description is not just, ‘The walls were yellow and the floor had a carpet,’ this is where you can kind of evoke what would a character notice.

If this person is in a really depressed mood, they’re going to start noticing some really depressing things about the room. The fact that that switch is broken, and it has broken for 10 years, and she’ll think about that later, whatever it is, that’s hideous writing, but you get the idea. Think about what you’re describing and how that description actually helps the scene itself.

Joanna: It’s funny because I think we also have default movement or actions. A lot of my characters, I’ll be reading, “Finn nodded,” and then someone else nodded, and then someone else nodded. And there’s a lot of nodding goes on and you have to go back and change out some of these actions for some other things.

Kris: Oh, absolutely. And this goes back to that, again, I am the person who has the spreadsheet of my overused words. And that’s why I always tell my clients that they need to go back to, ‘Look up in your manuscript, using the find function on whatever word processor you’re using, look for the word ‘Smile.”

And then, when I say, ‘Look for it,’ I also tell them to look for S-M-I-L, and that’s not because I don’t know how to spell the word smile but, if you use just S-M-I-L, it’ll catch every use of ‘smile,’ ‘smiled,’ ‘smiling,’ ‘smiles,’ any version of that. But I tell people, ‘Look for ‘Smile,” because sometimes we don’t realize it but our characters are almost maniacally smiling through our manuscripts.

Joanna: They totally are, all grinning.

Kris: There are so many ways to show happy and contentedness and love and passion besides smiling. And the same thing with smiling, turning, gesturing, nodding, sighing…oh my goodness, people wink more in manuscripts than they do in real life, I swear.

Joanna: I don’t even wink in real life, it’s not something I would do. I don’t think I ever put ‘Winks’ in my novels.

Kris: It’s amazing how many early writers I work with have characters who wink, and it’s often multiple characters who wink. And again, not that many people wink in real life so you have to be thoughtful with your winking.

Joanna: And look, we’re having a laugh, everybody listening, we’re having a laugh. And if you feel like you do one of these things, we’re not laughing at you, I’m laughing because I know I’ve done all of these things.

Kris: I do it.

Joanna: And it’s like, ‘Oh my goodness,’ when you go through this, you realize how many things you do. And it does take time to recognize this in yourself, so don’t worry, people, if you’re not aware.

That’s the other thing. When you’re new, you might not even be aware of some of these things over time. But another thing I wanted to mention was sentence variation. I’ve become very very sensitive to audio narration and when it’s a repeated rhythm of a sentence. The same number of syllables or similar sounds, then I really notice it because I listen to so much audio now.

So, in this edit, I’m making sure my sentences have variation. I guess that might be slightly advanced because a lot of people don’t write for audio.

In this world of increasing audio, what do you think about sentence variation?

Kris: It’s a very valid point. It’s true, whether you’re thinking about audiobooks or not, but just think about your go-to phrasing. Some people just have this poetic soul and they just write these sentences that go and go and go. But if your entire manuscript is made up of these sentences that just go and go and go, they might be beautiful but they also might tire out your reader.

The same thing goes if you are a writer who loves simple sweet short staccato sentences, they are great for pacing a fight scene or any sort of action-packed moment, but it gets tiresome to read these short quick sentences all of the time.

So any writer, definitely with audio, you definitely hear it more in audio, but any manuscript, you need to vary it up, lengths of the sentences, how you are starting your sentences. Often we have little preferences that we always start with a sentence with the subject of your character name or starting with the same type of phrasing at the beginning of a sentence, we just have to closely examine our habits because, as you said, every writer is coming to this from a different place.

Nobody is born a perfect writer.

So many times people think, ‘Oh, it’s a talented writer. He was born that way, she was born that way,’ but here’s the big secret. No one is born an amazing writer. Everybody has to learn. Everybody has to practice. Everybody has to put in that time.

We don’t like to tell people that part, we like to think, ‘Oh, our books have come out in their brilliance, we’ve always written this way,’ but there’s a lot of work involved in becoming a great writer. So this is all of that little nitty-gritty detail work that we just need to practice and take the time to learn because no one is good at this from the start. But we can be, every single one of us can be if we try.

Joanna: I think that’s the thing with some of the best-loved and well-known writers, they do things effortlessly so we think we can do that too, straight off the bat, where we’ve been reading for many many years so, clearly, we can write things.

The more you learn about story, the more you realize what there is to learn.

This is why I think I love being a writer because I feel like with every book you can learn something new and you can try something new and investigate and you’re always trying to make your storytelling better. And it’s just not something that happens straight off the bat. As you say, what am I, on number 17 or something? And I’m still going on. My goodness, what am I doing with this?

Kris: It’s been really funny for me because, as an editor, as I’ve been putting my own books out there, my first one was through a traditional publisher. And working as an editor with an editor on my own books, it was very funny because you could tell, the relationship again, and they were a little bit nervous thinking that I was going to be incredibly defensive about my punctuation or my organization of that manuscript, that was my first book which is called Get a Grip on Your Grammar.

I came into that relationship and I was like, ‘No-no-no, I love the editing process. Tear this apart, find every little nit-picky thing because relationships and readers make any project better.’ You know your own project so well but any relationship, even just a beta reader or friends in the creative-writing community, can make a project so much stronger just having other eyes on it.

Joanna: Other eyes are good.

Another thing I do on this level is to try and make things more emotionally-resonant. So, often I might have…we mentioned kind of smiling or whatever and trying to evoke emotion more but also adding elements of theme, any symbolism, that level that is deeper and it might only be little touches here and there.

What are some ways that we can deepen our writing?

Kris: Depending on what type of writer you are, sometimes people get really intimidated when they are writing their first draft of their project and they want this to be deep and thoughtful and have symbolism throughout. So they just kind of sprinkle it throughout, and that is one way to do it.

Oftentimes, I like to save a lot of the heavier touches like that, or I suppose you can see the lighter touches like that, for the later editing stages. This is where you throw in those false leads to the murder mystery, this is where you’ve realized that one character would be a great person to cast suspicion on, this is where you would have that little moment that you realize you have this beautiful symbol that your subconscious walked through there without you even paying attention to it, then you can kind of highlight a little bit more through your entire manuscript.

A lot of that work is something that, in my opinion, comes in the editing stage. Because if you try to do it while you’re writing, there’s only so much you can balance in your head at any given time, even if you are someone who is a heavy outliner.

A lot of that symbolism, or false leads, or just any sort of emotional resonance or atmosphere that you add in, save it for the later moments. And that’s where you really get to start thinking about how can you add tension, how can you add darkness, how can you add different levels of emotion. Just save it for a little bit later.

And again, this is where you can add details that, depending on how you describe something, you can evoke a very strong emotion or tone just in the way you describe the outside of that house. Think about how you can describe a house and make it a very optimistic moment. Think about how you can describe the exact same house but in a way that is terrifying.

It’s an interesting exercise in itself, but as you finish your book and you go back to these moments and you want to kind of create whatever atmosphere you’re looking for, just think about, ‘How can my description do it? And then, how can I have my characters’ emotions more on the page but never using the emotion words?’ That’s always the challenge with those emotions.

Joanna: We’ve talked about lots, but any more common issues, especially for newer writers, with editing a novel? Especially some people might be fantastic at writing nonfiction, for example, and then, they start writing a novel and they realize that it’s much harder than they expected.

What are any more of the common issues for new writers to watch out for?

Kris: Sometimes I feel like we fall into cliches without ever realizing we’re falling into cliches and we think we’re having this brilliant moment and we don’t realize that, not since The Wizard of Oz, starting with a dream or having the entire thing being a dream in the end, been quite as successful as we think it is. And it’s one of those things that you write this glorious moment but it was all a dream.

In the traditional publishing world, that’s a red flag that you’re probably not going to be getting a literary agent or publisher. I’m never going to say never by any means, but that’s just one of those signs that it’s a cliche ending that it was all a dream.

The same thing with starting the entire project with a dream. Be careful with that, it is overdone. So you have to be very thoughtful just to make sure that you’re not accidentally starting a project, for example, with a cliche beginning.

The same thing with, if you’re starting a beginning of a book or even the beginning of any given chapter, with a character waking up. That might be how they’re beginning their day but that doesn’t necessarily mean that’s where your story should begin.

Same thing goes with chapters that, just think about how riveting it is so wake up in the morning to slide your foot into the slippers, to walk down the hall, to pour yourself a glass of orange juice, this is not the most fascinating story ever. Obviously a writer could do it really really well but just always examine where you might be falling into some cliches of…that might be where you, as a writer, entered the story but that does not necessarily mean where your final draft actually should begin.

Joanna: That’s a good point actually. I think the jump-cut scene management is something that maybe people don’t understand. You don’t have to describe everything about a character’s life, as you say, you can cut from scene to scene without having to do all of that stuff. My characters frequently have an alcoholic drink or have coffee but they rarely eat. I mean they didn’t go to the toilet on the page.

Kris: Exactly, you just don’t need to include everything.

Joanna: I know exactly what you mean and some people don’t understand that if you watch a TV show, the jump cut is exactly what happens in a book. You can end a scene, you can end a chapter, you can put three little stars in it and jump to something else.

Kris: Exactly.

Joanna: What can an author do themselves and when is it a good idea to work with a professional editor?

Kris: I always challenge writers to work on their manuscript as much as they can by themselves with that first self-edit. And before you dive into your first edit, I always say, ‘Take a break from your book.’ If you just finished your manuscript, take a break from it.

If it’s a day, awesome. If it can be a week, even better. If it can be a month, fantastic. Your goal is to get yourself out of writing mode because your imagination is going, you know your character so well, you know your plot and your problems and all of these details so very well. But you need to edit, not as a writer, but you need to edit as a reader. So you need to be a degree separated from your project.

Also, you need time for that project to percolate, you need to be able to take a shower and have that epiphany of that moment in Chapter 3, which you know is kind of weak, and have that answer. You just need a little bit of separation from your manuscript before you dive into your editing.

And then, to really just think about that editing phases, not to start with Sentence 1, Chapter 1, and start reading through your manuscript looking for typos. That’s not where you need to begin. Think about big picture, and then the smaller picture, and then the final proofread.

And beyond the self-editing, always have eyes on your manuscript besides your own. And yes, this can be a professional editor and, as a professional editor, of course I will recommend that and I’ll talk about more of where that is a really necessary piece. But even if you have friends who are readers reading your book, if you have a writing group. Awesome. Critique partners, even better.

If you have people look at your book who are really thoughtful readers, no offense to anyone’s mother, but your mother might have a good tendency of giving you a pat on your back and saying, ‘I’m so proud of you. This is brilliant,’ or possibly the opposite.

You have to make sure it’s a reader who will give you valuable feedback, not just, ‘This is good,’ or, ‘huh, that was interesting,’ but someone who can read something and say, ‘you know what? There was that moment in that chapter that it was a little bit weak or that character’s falling a little bit flat.’ Just anyone who can give you really solid advice on something like that. If you have that person or find that writing community, there are so many amazing writing communities, whether in your local area or genre-specific that you can tap into, which is just so powerful.

And beyond, once you get some readers on your manuscript and take their consideration…and of course this is your book, you are the author. Just because somebody says something does not mean that you have to change something, you are the author and you get to make those final choices, but consider everyone’s advice, consider where everybody is hung up.

Because maybe what they’re telling you is something that is an issue, maybe what they’re saying as the answer is not the answer that makes sense for your book. But maybe if multiple people are having the same issue on the same chapter, maybe that’s time for you to re-examine it.

If you go through your own self-edit, if you go through a couple of readers, and you realize you’re still hung up, that’s a great place to have an editor come into the conversation. Or similarly, if you’re starting to do the traditional publishing world and you’re sending out queries or pitches and you’re starting to get past the query stage, people really like your query letter, that first letter you might send to a literary agent or to a publisher, but once somebody gets manuscript in their hands just it’s not moving past that stage, that’s a great moment to work with an editor.

It’s really important to notice that editors are not all doing the same thing. Just like we’ve been talking about different levels of editing, there are different styles of editors. You might have a developmental editor who is looking at those big picture pieces.

You might have copyeditors who are looking at, not only the micro editing but they’re looking at a little bit more of the grammar and the punctuation, all of that stuff. And of course your final editor that you would have is your line editor, or your proof reader, depending on what you want to call that person, and they would do the final sweep of your project.

Do give yourself some consideration, when you’re thinking about an editor, about what you actually need. In the past over 10 years of being a professional editor, I have had many many people calling me and saying, ‘I need a final proofread of my project.’ And I really want that to be true but so often we think we’re in that stage when we’re not quite there yet.

Think about what your book needs, and then, if someone tells you that you need to have a little bit more work on some heavier pieces, don’t just be defensive on that and say, ‘This is my baby, you don’t understand,’ pause and think on it for a moment and think, ‘okay, maybe there is something else to consider here.’

Joanna: Definitely. I have a story editor, so she’s my first reader, I don’t take anyone else’s opinion anymore. Jen, she does my story edit, and then, I do all my own stuff, and then, I have a proofreader before publication.

I learn something new with every book, so I am a total fan of professional editors and I’m a fan of your workbook, The Novel Editing Workbook, because, having all of these things that we can check off, obviously you have to do everything, otherwise you’d always be editing and never actually publishing, but it is really useful to have that. Which is why I got the book in print, because it’s good to remind yourselves of these types of things.

Where can people find you and your books and everything you do online?

Kris: You can find everything I do at kris-spisak.com. But I realize that no one will ever get spelled that correctly so you could also find it all at getagriponyourgrammar.com, which is a redirect to my webpage. And there you can find the blog that really started my entire career.

I had an accidental blog that exploded and turned into an indie-published book, turned into a literary-agent deal, and then, a book traditional book deal. So, the blog that started it all is still going. I have a writing-tips blog there, I have a podcast there, I have a sign-up for my monthly newsletter of writing tips there. And I love connecting with folks, so do check it out.

Joanna: Thanks so much, Kris, that was great.

Kris: Thank you so much, Joanna.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn