In February the Center for Fiction, a New York City institution devoted to the creation and enjoyment of fiction, moved from Midtown Manhattan to a new space in Downtown Brooklyn. “The Center for Fiction has a history of moving to the city’s cultural center,” says Noreen Tomassi, the center’s executive director. “I was very excited about the Brooklyn Cultural District—it’s where much of our audience is, and it’s where we can serve families. And it’s an area with incredible public transit access.” The organization has relocated many times since it was founded in 1820 in Lower Manhattan as the Mercantile Library, decades before the New York Public Library opened. In its early years the private lending library hosted appearances by Frederick Douglass, Mark Twain, and John Rollin Ridge, one of America’s first Native American novelists. Now the center is a full-fledged nonprofit that hosts readings and writing workshops, sponsors fellowships and prizes for fiction writers and editors, and runs educational programs for kids from low-income families, among other programs.

At more than seventeen thousand square feet, the newly constructed space, adjacent to the Mark Morris Dance Center and steps from the Brooklyn Academy of Music, is roughly the same size as the center’s previous location. With the new building’s open layout, however, the center can host more public events and offer more amenities to members and visitors. Tomassi expects membership to double in the new location. “The dream for us was to create a space in New York City like the great houses of literature in Europe for people to read and write books together,” she says. “It’s a beautiful tradition.”

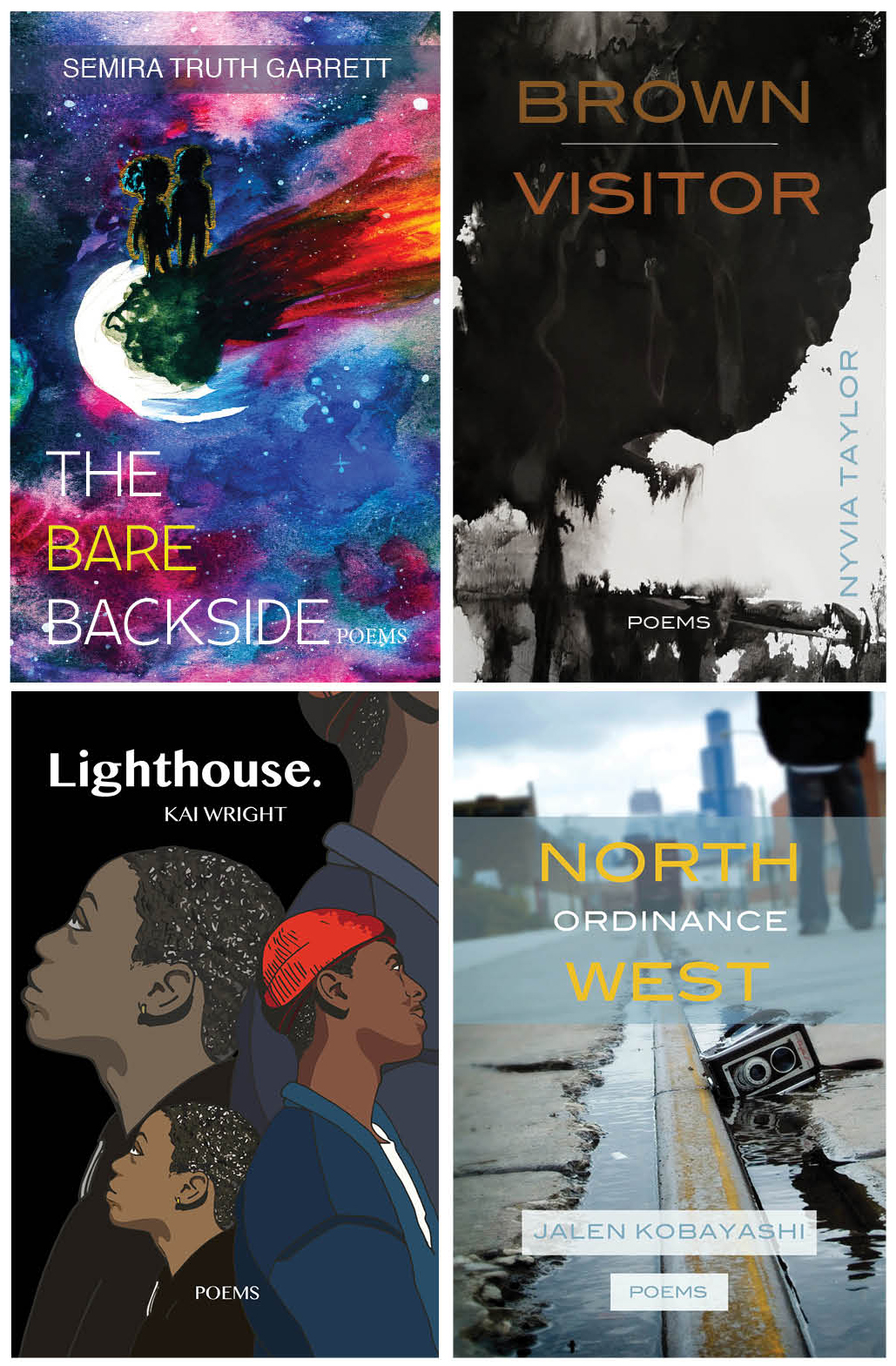

The ground-floor auditorium, the venue for the center’s programming, can seat roughly 140 people and is available for all manner of public and private events, from readings and book parties to film screenings and weddings. The center has already scheduled a number of readings, conversations, and screenings for the spring, featuring writers such as Laila Lalami and Maaza Mengiste (March 27), Geoff Dyer (April 4), Deborah Eisenberg and Alexander Chee (April 16), and Paul Auster with high-wire-artist Philippe Petit ( June 6). Through the KidsRead program, children from low-income families and nearby schools are also invited to participate in literary events; authors Kwame Alexander and Jacqueline Woodson will headline a KidsRead event on April 1. Seven classrooms offer four times the educational space of the previous building, allowing for an expanded catalogue of writing workshops and reading groups, and much of the new space is open to the public, including a café and bookstore that stocks titles from both major publishers and independent presses as well as works in translation.

Members, who pay $150 a year, have access to a private reading room and can borrow from the center’s eighty-five thousand books of fiction, including its award-winning mystery collection. For an additional fee members can use one of eighteen desks in a private, sunlit writers studio. Edgar Allen Poe wrote short stories in the Mercantile Library’s first such space in the 1830s; more recently, Megan Abbott and Alexander Chee worked on their novels at the Midtown location. During off-hours Chee spread out sections of his most recent novel, The Queen of the Night, and wandered the stacks for inspiration. “There was a magic to being more or less alone in a seven-story library that I needed for this novel, so much,” he says.

In designing the new space, the center’s leadership, along with Julie Nelson of BKSK Architects, made every effort to appeal to a literary audience. “The encounter between reader and writer is personal, individual,” Tomassi says. “How do you take language and make it visible and dynamic and spatial?” A careful observer might notice writing prompts etched into glass, a bench fashioned from books, and other furnishings that honor the Mercantile Library’s history, such as the bookstore’s chandeliers, which are giant replicas of a lamp once housed in the stacks.

Like Tomassi and her staff, author Michael Cunningham, a member of the organization’s Writers Council, is excited about this new chapter for the Center for Fiction. “I’m thrilled that it’s going to be a place where writers can go to work and hang out with others who share the belief that writing matters,” he says. “In a world that is paying less and less attention to fiction, this kind of bald assertion of its importance is a remarkable gift.”

Jonathan Vatner is a fiction writer in Yonkers, New York. His novel, Carnegie Hill, is forthcoming from Thomas Dunne Books in August.