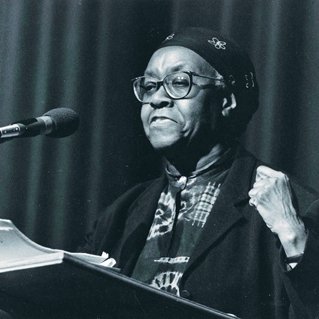

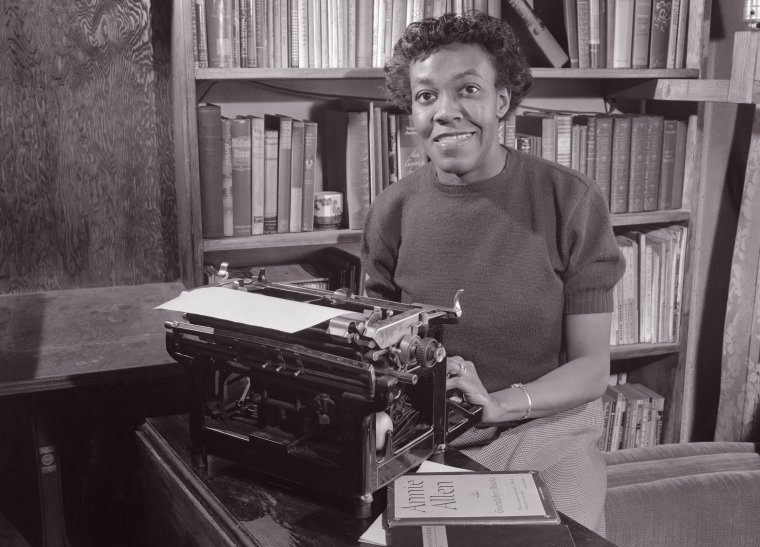

In September 1935, after completing high school, Gwendolyn went directly to the new Woodrow Wilson Junior College, which had just opened its doors at Sixty-Eighth and Wentworth. She would graduate in 1936. While at Wilson, Gwendolyn enjoyed friendships, worked hard at her studies, and wrote regularly. More and more, her work began to engage Negro people, the people of her community, and the world at large.

Bolstered by the openness of the college experience, the communion of friends, the recounting of events of the day over radio, newsreels, and in the newspaper, she gave a passionate and urgent cry in response to the Italian dictator Mussolini, ally to Hitler. She responded to the rumblings of a world soon to be at war on October 12, 1935, in yet another contribution to the Chicago Defender :

Words for Mussolini

“Dark men must learn to bow to bright”

How many, many times a flesh

of black has masked a soul of white.

Lord, Lord, I ask this gift of You!!

Grant me a voice, and speaking eyes.

That the quick-throbbing truth I know

May reach the deeps of earth and skies.

I want to tell them all in words

Shining and hard, and very cold,

This message that I know is Yours—

Else whence the richness of its gold?

I want to tell them that the sod

Is drab and deeply dark of hue,

Yet their material nourishment

From out the hated blackness grew.

The rose whose sweets they cherish sprang

From that same blackness they despise.

A hundred times I beg of You—

Grant me a voice, and speaking eyes.

Thus, Gwendolyn pleaded with eloquence and fire. She implored God for “a voice, and speaking eyes.” And she would have these two major gifts.

Even though Gwendolyn herself demonstrated some ambivalence about the color of her skin and the color of her soul, she turned her gifts on intraracial conflicts of self-acceptance and self-love. Having gained perspective through age, experience, and self-confidence, she rebuked self-hate over and over again.

In a poem that she noted was “to be published in Opportunity,” the journal of the Urban League, she scoffed at the woman who wrote on a job application that Gwendolyn had “Negroid features, but they’re finely spaced.” Gwendolyn felt the apology in the qualifying conjunction “but.” She would have better phrased the sentence, “I’ve Negroid features—and they’re finely spaced.”

Gwendolyn celebrated “A Brown Girl” (April 8, 1936): “But there is one tall brown girl: How high and fine her head / Her mouth, how firm; her eyes how cool; / How straight and strong her tread: / As if to say, ‘I have no fear.’” This poem is reminiscent of the celebratory poetry of the Harlem Renaissance, the Negro Renaissance stressing racial pride.

In print, Gwendolyn celebrated the beauty of Negroness, and she castigated intra-racial colorism. She was bold and public in her address. But Gwendolyn also created a handmade volume of unpublished poems dated July 23, 1936, shortly after she graduated from Woodrow Wilson Junior College. It would include poems written from 1935 to 1936. She entitled it Songs After Sunset, suggesting work composed in near darkness, in quietude, away from the business of the day. These “songs” are mostly love poems “both worldly (friendship, marriage, nature) and divine (animism, God, Nature).” These poems are profoundly private—and universal.

WE

An old man said this thing to me:

“The loveliest word of all is ‘we.’”

Gwendolyn had been keeping notebooks since she was eleven and named them for each year, except for 1932, which went missing. These notebooks were named variously My Fancy Book, The Red Book or The Merry Book, The Blue Book of Verse, The Account Book, and Book of Thoughts.

She was so devoted to writing in her notebooks that at one point her mother grew concerned. To divert Gwendolyn’s attention, and save her eyesight and health, she poked her head into Gwendolyn’s room one day.

“There’s a big fire down the street,” Keziah told her daughter.

“Yes,” Gwendolyn said, and kept on writing. She was creating.

But her mother was her chief champion, taking her to a lecture and reading by the esteemed James Weldon Johnson, writer of “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” He was also the author of God’s Trombones, poems of sermons of Negro preachers; was the national secretary of the NAACP; and had been the United States consul to Venezuela. He was a Great Man. A Great Negro. Gwendolyn was tongue-tied at the thought of meeting him. She too wanted to do Great Things.

Years before, in 1933, when she was sixteen, Gwendolyn had sent some of her poetry to James Weldon Johnson. He had been kind in his reply and had offered valuable, encouraging feedback and legitimate and constructive criticism. On August 30, 1937, he wrote to her:

My dear Miss Brooks:

I have read the poems you sent me last. Of them, I especially like Reunion and Myself. Reunion is very good, and Myself is good. You should, by all means, continue you[r] study and work. I shall always be glad to give you any assistance that I can.

Sincerely yours,

James Weldon Johnson

In addition, he wrote kind and insightful notes in the margins of the poems.

Dear Miss Brooks—You have an unquestionable talent and feeling for poetry. Continue to write—at the same time, study carefully the work of the best modern poets—not to imitate them, but to help cultivate the highest possible standard of self-criticism.

Then he offered meticulous and generous criticism of poems she had sent. The poems included “Once She Lived,” “Decay,” and “Aftergloom,” poems befitting a sensitive, young woman with a serious, even morbid, bent.

Gwendolyn took Johnson’s responses to heart. They discussed eliminating unnecessary words and feeling free to break the rigidity of the measured form. She knew the works of certain Negro poets such as Langston Hughes and Countee Cullen. Now she turned her attention to T. S. Eliot, Ezra Pound, and e. e. cummings.

So the prospect of meeting James Weldon Johnson was thrilling.

Gwendolyn and her mother went to their church, Carter Temple Colored Methodist Episcopal Church, on the northwest corner of their block, to hear Johnson’s lecture. Her mother was aggressive, pushy for her talented, shy child.

“She’s the one who sent you all those wonderful poems!” Keziah enthused to Mr. Johnson.

He responded coldly. He was hoisted high inside of himself. He crossed his arms in front of his chest and lifted to full height. “I get so many of them, you knooow.”

Gwendolyn felt her face go hot. Why had she supposed he’d be otherwise? He was, after all, a Great Man of Achievement.

Her meeting with poet-writer Langston Hughes was kinder. Again, her mother took her to a church. This time it was Metropolitan Community. They went to meet this Great Man of Letters, a poet in touch with the pulse of the people and the pulse of poetry itself. He laughed gently and warmly upon meeting Gwendolyn and her mother.

Ever dreamy-eyed and practical, Keziah Wims Brooks insisted that her daughter show Hughes her poems. He read them on the spot, then leaned forward and gazed directly at her. “You’re very talented!” he exclaimed. “Keep writing! Someday you’ll have a book published!”

He was a soft-spoken man, but his words had weight. Standing there in church, he provided a gospel of clarity and empathy. His friendship would follow Gwendolyn through the years.

After graduating from Wilson Junior College, Gwendolyn went in search of a job. Her family needed her. She could not live by poetry alone. She was nineteen years old, able-bodied, educated, and expected to work. She of the “voice and speaking eyes” was a natural reporter. She not only liked to observe clouds, as she did on the back porch, but also liked to study people. She loved to listen in on the gossip between neighbors. At thirteen, she reported all that she had seen and heard in her own handwritten rag, the Champlain Weekly News. It sold for five cents. The press of schoolwork had caused Gwendolyn to cease publication of her newspaper. Now, Dewey Jones, who edited the Lights and Shadows column of the Chicago Defender, where Gwendolyn’s poems were printed almost weekly, encouraged her to interview for a job as a reporter on the paper. Gwendolyn wrote to publisher Robert Abbott, posthaste. His reply was welcoming. An appointment was set up.

Gwendolyn and her mother met Abbott with anticipation. At first he met them with welcome on his countenance. Quickly, though, the warmth turned to cold stone. He was abrupt. “If we hire you, you will have to be on time every day.” The meeting was over. They were dismissed, and she did not hear from him again.

Gwendolyn sensed she had met the stone wall of color prejudice. Robert Abbott was color-struck. That is what Negroes called his strict preference for light-skinned Negro women.

Not to be deterred from her journalistic instincts, Gwendolyn again published her own newspaper. This time it was mimeographed. The News-Review sold for a nickel. A remaining copy demonstrates that Gwendolyn was in touch with cultural affairs and current events. This issue included local news and a speech by associate justice of the US Supreme Court Hugo L. Black. Gwendolyn’s brother, Raymond, contributed a cartoon of Justice Black, a former Klansman, saying, “I number among my friends many members of the colored race.” Along with the quote is an image of a black man hanging from a tree.

Gwendolyn contributed a poem, a short story, and an editorial, as well as biographies of Negroes of achievement. She quoted Emily Dickinson, William Shakespeare, and the Reverend Harold Kingsley “on the endurance of blacks.” There was a Negro authors quiz, including luminaries from the Harlem Renaissance.

Young Gwendolyn was a race woman, but she had to get a job. She worked for spells in domestic service. She went to the Illinois State Employment Service, which sent her to the Mecca Flats Building at Thirty-Fourth and State Street. It was a nine-block walk from the Brooks household.

Opened initially as a hotel in 1893, the ninety-six-unit apartment complex, known as the Mecca, was built on the edge of the Black Belt for upwardly mobile Negroes. Its fame spread far and wide. The dream of it sparked the imaginations of children and adults all the way to the Deep South.

At the Mecca, Gwendolyn would work for a “spiritual adviser,” E. N. French, who made huge sums of money off the dreams, desires, and longing of needy and sick people. Gwendolyn, with other workers, answered imploring letters and bottled so-called curative medicine for the charlatan. These bottles, meant to attract love and money and good health and the resolution of difficult situations, were delivered by Gwendolyn and others throughout the Mecca. Ever the observant reporter, Gwendolyn witnessed “murders, loves, lonelinesses, hates, jealousies. Hope occurred, and charity, sainthood, glory, shame, despair, fear, altruism.” The young poet became intimately acquainted with the vast edifice and its denizens.

She worked among this spectrum of dark humanity for four months, for eight dollars a week, a portion of which she contributed to the Brooks household. She kept the job out of necessity but had to let it go when the “spiritual adviser” wanted to promote her to associate pastor. It was a job that would have entailed some preaching on her part. Gwendolyn could deliver potions, but she wasn’t to deliver false notions or preach promises made of air. She would store the Mecca and its members in the storehouse of her mind and call up the innumerable nuances years later, failing to create anything significant about the place, again and again, until many years later. For now she still lived at home and gathered life around her in her mind.

The Brooks household was as gentile and orderly as an Elizabethan garden with each stick of furniture, knickknack, doily, and child in its place. David Brooks, head of the family, sang in a rich baritone while he worked around the house after working at McKinley Music Company. He sang his songs and went about family life good-naturedly. He could fix anything. He fastened pipes and the rivulets of water ran down his strong, black arms while he fixed the plumbing. He nailed down loose floor boards; he yanked out bent nails. He made the world right. He had studied medicine for a year at Fisk University in Nashville. His studies had ended when he started a family. He welcomed his children and loved to fulfill his doctoring skills on them. He fed them spoonfuls of cod-liver oil. He sat by Gwendolyn and Raymond’s bedside and spoke softly to whichever of them was sick. He had a beguiling bedside manner and knowledge gleaned from reading and black folk medicine. Gwendolyn thought her father made her times being sick and convalescent worthwhile.

Her mother, Keziah, was dutiful, performing chores with supreme efficiency. Her house was immaculate. Her children were scrubbed and lotioned. But she made no outward displays of affection. Yet all the household tasks she performed so cheerfully, the caring and encouraging words, her vigorous pursuit of her children’s excellence, were proof of a deep maternal love.

By the 1930s, when Gwendolyn was a precocious preteen and teenager, she observed all manner of people, dressed in their best, strolling down the avenue, on their way to Forty-Seventh and South Parkway. In the vicinity of the Brookses’ household, seven blocks away, vendors lined Forty-Seventh Street. The Regal Theater, which opened its doors in 1928, was nearby, part of a complex that also included the Savoy Ballroom, a Walgreens, and the South Center Department

Store, with the Madame C. J. Walker Beauty Salon and Walker School of Beauty opened. The complex was built by Harry M. and Louis Engelstein, white men in pursuit of the Negro dollar. When Negroes had money, they spent it in their community because they had to. There was nowhere else to go.

The Regal Theater was magnificent, an alluring palace of marble floors and decorative cornices. Its seat covers were imported from North Africa. Its chandeliers, made of crystal, came from Belgium. Artwork suggesting Moorish castles under a North African sky of stars enclosed the space. The Regal was the place to be. And all of Bronzeville, the classes of the Black Metropolis, went there. The Regal Theater attracted the whole of the Negro community because it attracted the headliners of the day, as well as rising local talents. It offered films as well, like Flying Down to Rio with Chicago’s Etta Moten Barnette, whose husband, Claude, was the head of the Associated Negro Press. It showed features with Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn, and Spencer Tracy. Its live stage shows featured comedians and performers that included Paul Robeson, Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Ethel Waters, Count Basie, zoot-suiter Cab Calloway, banana-leaved Josephine Baker, and tap dancer Bill Robinson. Gwendolyn, her mother, and brother went to see movies at the Regal Theater that stirred Gwendolyn’s romantic fantasies, and she went to see live stage shows that she would write about later.

Within a four-block radius of the central site of Bronzeville—Forty-Seventh and South Parkway—was Providence Hospital, at Fifty-First just off South Parkway, staffed by Negro doctors and nurses. There was also the George Cleveland Hall Branch Library on Forty- Eighth and Michigan Avenue, with its impressive collection of work on and by Negroes in the Vivian Harsh Research Collection of Afro- American History and Literature; the South Parkway Branch of the YWCA; and the Michigan Boulevard Garden Apartments. Each of these would be significant to Gwendolyn’s life and work.

The NAACP Youth Council held its meetings at the YWCA building and, in 1937, Gwendolyn, at the urging of Lula Battle, her friend from Wilson, attended a meeting and joined the group. The council included an ambitious group of progressive, forceful, young intellectuals who would accomplish significant things. They were not leftists, but they pressed against the status quo of repression and poverty assigned to Negroes. Of the members, Joseph Quinn, head of the council, would become a teacher in California; Sarah Merchant, important to Gwendolyn in another way, would also become a teacher; George Coleman Moore, a teacher as well as a writer; Theries Lindsey, a friend from Wilson days, would become an attorney; and John H. Johnson would found and build a media empire that included Ebony magazine, Jet, Negro Digest/Black World magazine, Ebony Jr., Fashion Fair cosmetics, and the Ebony Fashion show. Last, but not least, was Gwendolyn’s friend Margaret Taylor Goss, who became a renowned painter, writer, cofounder of the South Side Community Arts Center, and founder/ director of the DuSable Museum of African American History.

The camaraderie among NAACP Youth Council members was intense, and Gwendolyn entered a more active and activist moment in her life. Thelma Johnson, president of the council, and Margaret Goss created a sense of hospitality and community for the members. They socialized together and held dances and gatherings, but they also engaged in meaningful and substantive talk. Gwendolyn was still reserved, but she began to blossom in a space suited for her passionate interior. She entered into the activism of the group, protesting against lynching. Council members wore paper shackles around their necks, symbolizing the lynch rope, and marched, carrying placards protesting the wrong done to the Scottsboro boys in Alabama. And Gwendolyn went to dances and danced. She was accepted as a writer, a thinker, and a committed race woman. Her peers in the council were young, gifted, and Negro, and it was the end of the 1930s in Chicago, in Bronzeville. She was finally one of the group.

Gwendolyn was a little girl during the Harlem Renaissance, which stretched well beyond New York. Being Negro was in. Negroness was even in vogue on Broadway in shows like Shuffle Along and whites infiltrated Harlem to be entertained at nightclubs where light-skinned beauties danced in their glory. All this activity flurried in the air like flecks of smoke from a stupendous fire that was headquartered in Harlem but fanned out across the nation. It swirled down to a quiet street in Bronzeville and a young Negro girl named Gwendolyn. And in the 1930s, new embers of another Renaissance were starting to burn in Bronzeville. Chicago was the perfect place for another Renaissance. In the 1920s, Chicago’s Black Belt had been the center of economic and political power for Negroes. This crucial power was based upon many institutions that had been established from 1890 to 1915, including a bank, a hospital, a YMCA, an infantry regiment, effective political organizations, lodges, clubs, professional baseball teams, social service institutions, five newspapers, and a number of small businesses. Yet before there could be a flowering, there was a Depression to survive.

The Depression years (1929–1940) were felt in the Brooks home. Even though Negroes claimed often that they didn’t feel the Depression because their community was always in a state of depression and just getting by, the Great Depression hit hard. There was mass unemployment—factory and mill layoffs, domestics lost their jobs. Twenty-five million men were out of work—both Negro and white.

After Franklin D. Roosevelt won the election, in 1932, lengthy relief lines for government assistance lined the street. There were work programs instituted to offer employment to hungry people who were looking for more than a handout. They wanted a leg up, some boot straps to pull themselves up by.

In the Brooks household, father David often brought home twenty-five dollars a week during the best of times at the McKinley Music Company. During the worst of times, during the Depression, he brought home eight to ten dollars a week. Gwendolyn’s parents quarreled over money and even separated for a time, during which David took Gwendolyn and her brother, Raymond. But the family was reunited, and David took on a second job, house painting. It was during those trying times that Keziah Wims Brooks changed the family menus from lamb, hamburger patties, and chicken with potatoes and vegetables to beans, beans, and more beans. They ate the beans without complaining. Some people had less. Yet whatever was on their table, they welcomed to it hungry strangers who knocked at their door.

After dinner, David Brooks would spend quality time with his children. He had a deep love of books and read to them Paul Laurence Dunbar poems. He sang songs to them and he told them stories. He told them about his father, who had been a slave. Once his father had achieved freedom, he moved to Oklahoma. He was enterprising and proved to be a successful farmer. In turn, his white neighbors grew envious and poisoned his mules and horses. So he moved. From this family story, Gwendolyn learned about the poisonous power of envy and knew it was something to guard against. Her father told them all the things he had seen in the world, especially the events of the summer of 1919. The Depression that hit some years later was hard, but the Red Summer of 1919 was harder.

David and Keziah had brought newborn Gwendolyn from Kansas to Chicago just two years before the Red Summer, when postwar race riots swept American cities. Hundreds, mostly black people, were killed. In most cases, whites had attacked Negro people. In Chicago, whites got more than they bargained for: the blacks fought back. Robert Abbott of the Chicago Defender had exhorted black people in a 1915 slogan, “If you must die, take at least one with you.” (Never mind that Abbott was the same man who treated Gwendolyn coldly during a job interview because her complexion was not light enough.) Negroes in Chicago did just that. Chicago was what white poet Carl Sandburg called “the Hog Butcher for the world.” It could cut a man down. One had to be tough to survive in Chicago.

Gwendolyn Brooks came from this community of tough-minded people. She would sit at her desk now in the late 1930s, more mature, more conscious of herself and her world. Her calling was clear—to write, and that included writing about her surroundings. She was surrounded by life, by Bronzeville.

Excerpted from A Surprised Queenhood in the New Black Sun: The Life & Legacy of Gwendolyn Brooks by Angela Jackson, forthcoming from Beacon Press on May 30, 2017. Reprinted with permission from Beacon Press, 2017.

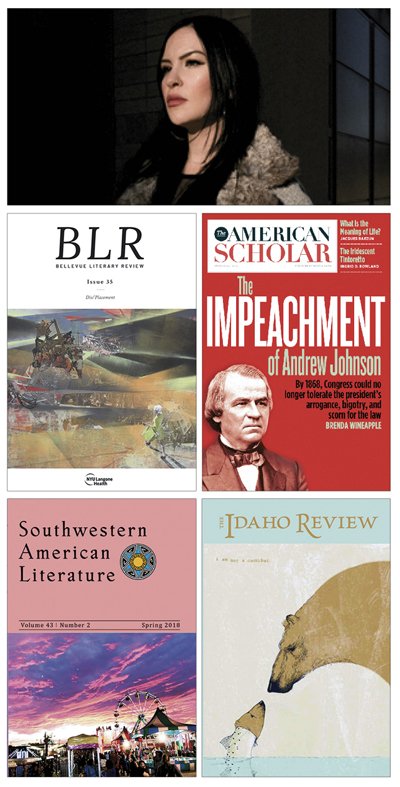

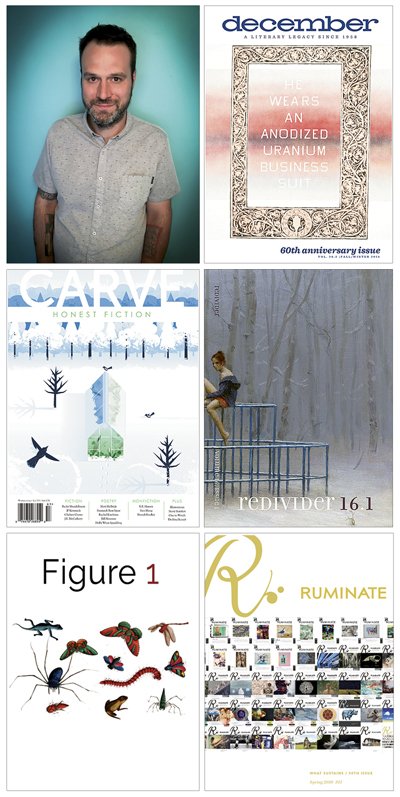

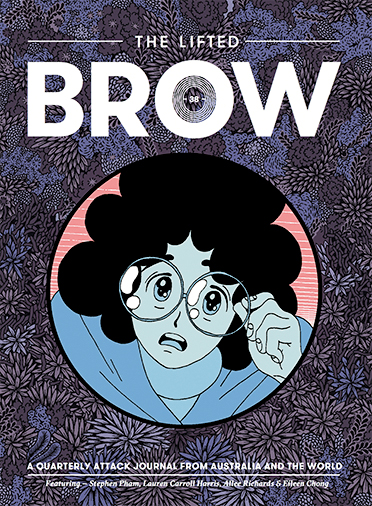

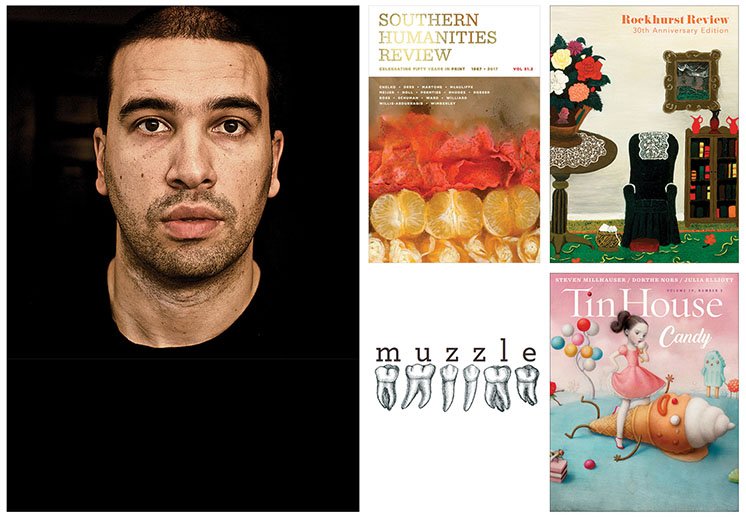

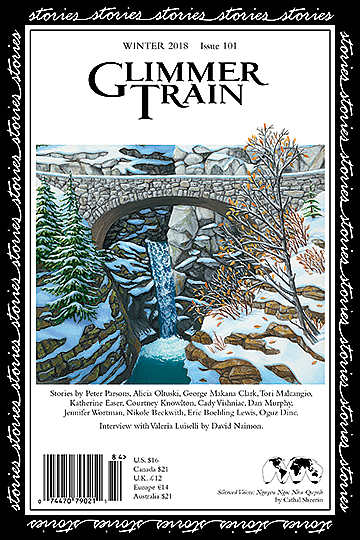

When I find journals that run essays containing bad behavior, deep reflection, and curse words, I send to them,” says Aaron Gilbreath, who published nearly every essay in his debut collection,

When I find journals that run essays containing bad behavior, deep reflection, and curse words, I send to them,” says Aaron Gilbreath, who published nearly every essay in his debut collection,  “Lit mags feel like old-school garage bands to me. When they aren’t tethered to commerce or some sales team’s expectations, they can focus on delivering highly charged, less commercial creations to a dedicated audience,” says Gilbreath, who seems to have found this in the New Orleans–based print biannual Bayou (

“Lit mags feel like old-school garage bands to me. When they aren’t tethered to commerce or some sales team’s expectations, they can focus on delivering highly charged, less commercial creations to a dedicated audience,” says Gilbreath, who seems to have found this in the New Orleans–based print biannual Bayou (

The closing essay of Gilbreath’s collection, “(Be)Coming Clean,” first appeared in the Louisville Review (

The closing essay of Gilbreath’s collection, “(Be)Coming Clean,” first appeared in the Louisville Review ( “When I wrote an essay about sleeping in my car and stealing hotel breakfasts in order to see bands play on a limited budget, and questioning my parental potential,” says Gilbreath, “the Smart Set immediately came to mind.” The Smart Set (

“When I wrote an essay about sleeping in my car and stealing hotel breakfasts in order to see bands play on a limited budget, and questioning my parental potential,” says Gilbreath, “the Smart Set immediately came to mind.” The Smart Set ( According to its editors, the print annual Hotel Amerika (

According to its editors, the print annual Hotel Amerika (

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?

How has Amistad changed or grown in the past thirty years?