Peter J. Stavros

Louisville,

KY

40207

Louisville,

KY

Louisville,

KY

40207

Louisville,

KY

40207

Louisville,

KY

40207

“They taste good to her / They taste good / to her. They taste / good to her…” Rafael Campo reads William Carlos Williams’s poem “To a Poor Old Woman” and speaks with Elisa New about enjambments, plums, and empathy for Poetry in America.

“In the days since her arrest, Mary Ripley has not slept—ironic, since sleeping is precisely what she was doing on the night her landlady was murdered.” In this short animation, Christina Dalcher narrates her seven-sentence story, “The Burden of Proof.” Dalcher is the author of the debut novel, Vox (Berkley, 2018), which takes place in a dystopian United States where women are only allowed to speak one hundred words per day.

“I like to have a story be just the essential.” Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, author of Friday Black (Mariner Books, 2018), talks about why he enjoys the short story form, writing Black characters, and his connection with his students in this Late Night With Seth Meyers interview.

Chicago,

IL

60613

“A few times a year, usually in the dead of winter, I’m overcome by a remarkably strong urge to simply disappear. I pack up my cats and computer, climb in the car, and head to my family’s summerhouse in Rhode Island, which I am fortunate to have, and where I often remain for weeks on end. Once there, I am absurdly habit-forming: I write from nine to three; take long, music-fueled walks along the river; write again from five to seven; and finally reward myself with red wine, dinner, and whatever TV show I’m currently immersed in. I wear clothes from high school and stop shaving my legs; often, I won’t see another human being for days. I try to give myself permission to falter, to squander whole mornings, and I find that after a few days, almost unfailingly, the words start to well up. It comes to feel as if time has contracted, as if my real life were a memory, as if the page and frozen view beyond the window were the only truths that matter. There are other tricks, of course—returning to the books that made you ache to be a writer (for me it’s often Patrick White’s The Tree of Man, or Joan Didion’s The White Album); writing by hand about the writing—but when it comes to reconnecting with the work, I find there’s nothing quite like absenting yourself from the world.”

—Katharine Smyth, author of All the Lives We Ever Lived: Seeking Solace in Virginia Woolf (Crown, 2019)

“I come from the fire city / fire came and licked up our houses, lapped them up like they were nothing / drank them like the last dribbling water…” This Motionpoems short film, directed by Daniel Daly and starring Khadija Shari, features Eve L. Ewing’s poem “I come from the fire city.” from her debut collection, Electric Arches (Haymarket Books, 2017).

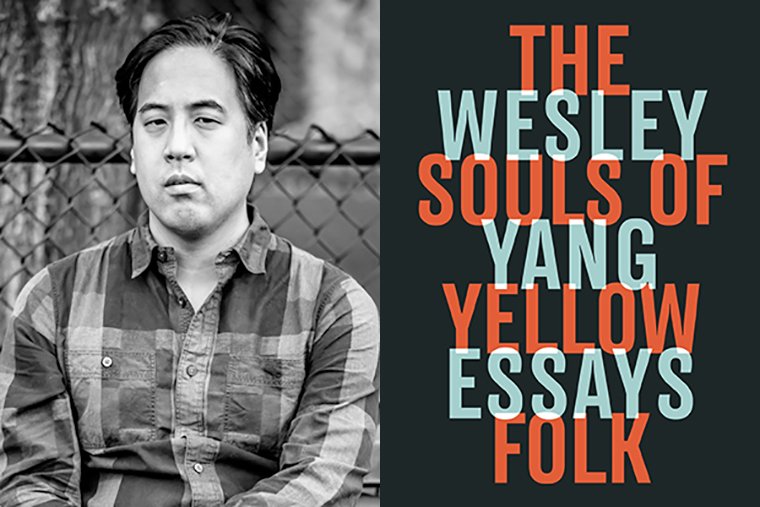

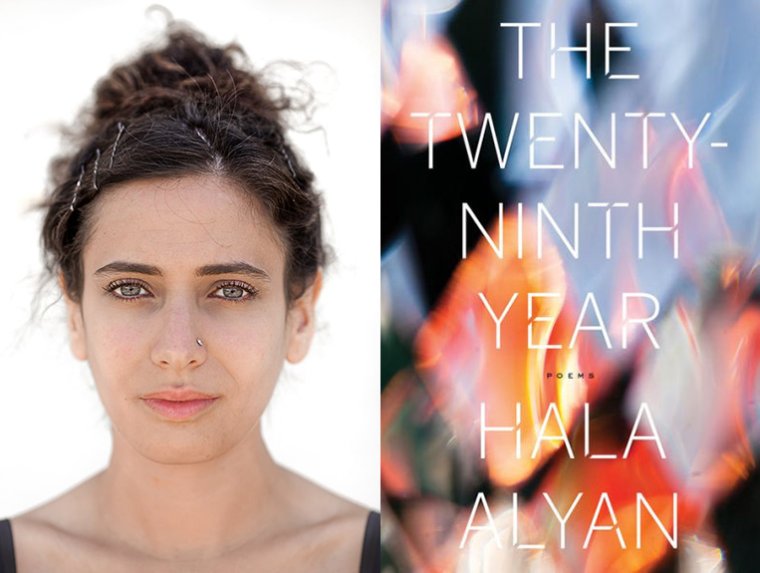

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Hala Alyan, whose fourth poetry collection, The Twenty-Ninth Year, is out today from Mariner Books. In wild, lyrical poems, Alyan examines the connections between physical and interior migration, occasioned by the age of twenty-nine, which, in Islamic and Western tradition, is a year of transformation and upheaval. Leaping from war-torn cities in the Middle East to an Oklahoma Olive Garden to a Brooklyn brownstone, Alyan’s poems chronicle a personal history shaped by displacement. “Alyan picks up the fragments of a broken past and reassembles them into a livable future made more dazzling for having known brokenness,” writes Kaveh Akbar. “This is poetry of the highest order.” Hala Alyan is an award-winning Palestinian American poet and novelist as well as a clinical psychologist. Her previous books include the novel Salt Houses (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2017) and the poetry collections Hijra (Southern Illinois University Press, 2016), Four Cities (Black Lawrence Press, 2015), and Atrium (Three Rooms Press, 2012).

1. How long did it take you to write The Twenty-Ninth Year?

I wrote it in bits and pieces over a year, and then stitched it together into a coherent collection in a few weeks, which is usually how I work with poetry.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

Much of it was written from a state of pain—psychic, emotional grief, a time in my life that involved a fair amount of evolution and “lying fallow,” as my friend put it. At times I found it difficult to write about an experience I was still in the middle of, which is why I had to wait to iron out the narrative until things felt more settled.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I’m not picky about location. I make sure to write thirty minutes a day, though that generally is for fiction, which I have a harder time being disciplined about. In terms of poetry, I usually wait until I need to write, which makes for a really thrilling, cathartic experience of creation.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

Just how involved and long the process can be! How many beautiful, moving parts have to work together just to create a book, and how much you need dedication and love for the process from every single person involved.

5. What are you reading right now?

At the moment, I’m rereading Virgin by Analicia Sotelo as well as The Mars Room by Rachel Kushner.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

That’s such a difficult question, because I wish all good writing (especially by writers of color) had equal recognition—an impossible want, I know. There’s several books coming out or recently out by women of color that I’m really hoping soak up a ton of recognition: Invasive Species by Marwa Helal, To Keep the Sun Alive by Rabeah Ghaffari and A Woman is No Man by Etaf Rum.

7. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I wish the different parts of the community were more integrated. Starting off, I knew virtually nothing about the publishing industry, for instance, which seems like an oversight. I would love to have more interaction with different members of the writing, reading and publishing community—to know more about what publicists do, to talk to more booksellers and libraries, to really be reminded that we’re all in this together!

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

My easily distracted nature: laundry, walking the dog, making oatmeal. Although I also think that these are necessary parts to a writing life, as is work (for me) and procrastination and daydreaming.

9. What trait do you most value in an editor (or agent)?

A combination of honesty and empathy, which I’ve been lucky enough to find both in my agent and the editors I’ve worked with so far. I also like a bit of tough love, because it brings out the eager student in me.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

I like to toss Anne Lamott’s Bird by Bird at anyone who is even remotely interested in writing. In particular, I love her approach to breaking down a massive writing task into small, digestible pieces, and finding joy in those pieces.

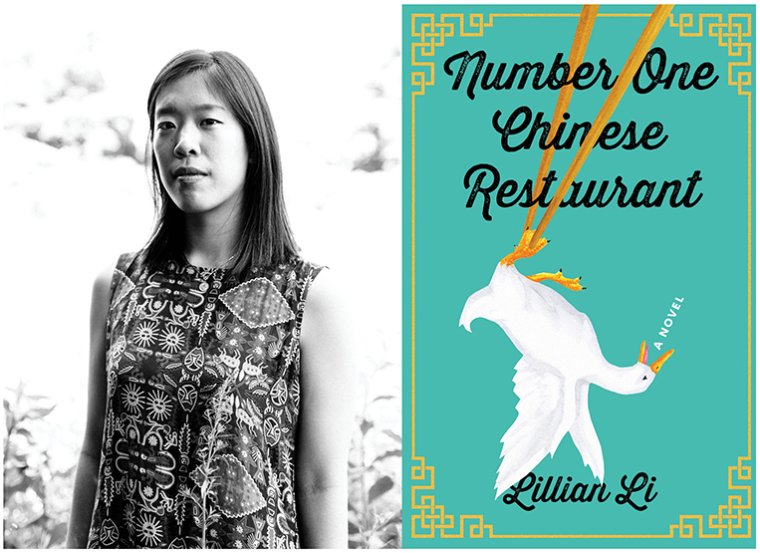

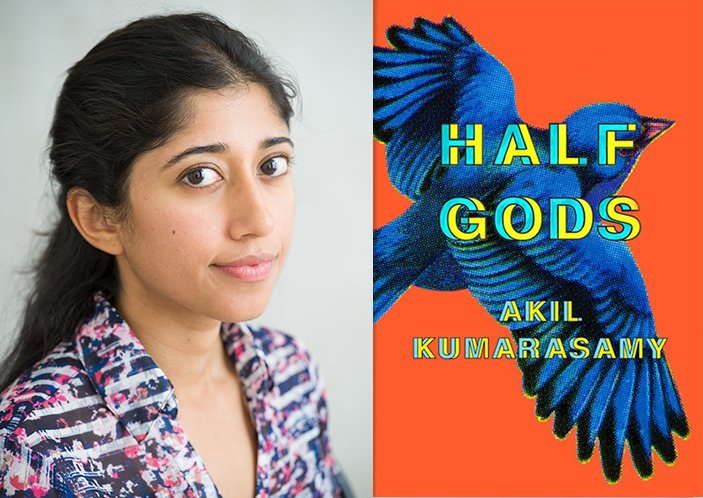

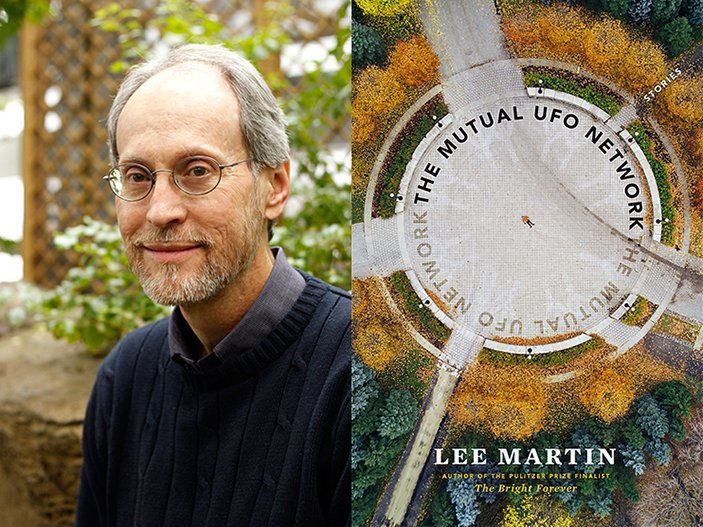

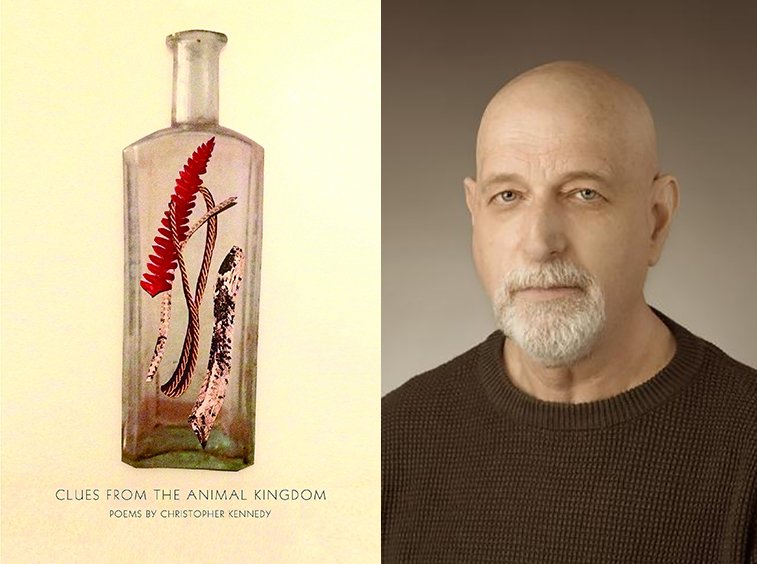

For our seventeenth annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five established authors to introduce this year’s group of debut writers. Read the July/August 2017 issue of the magazine for interviews between Zinzi Clemmons and Danzy Senna, Hala Alyan and Mira Jacob, Jess Arndt and Maggie Nelson, Lisa Ko and Emily Raboteau, and Diksha Basu and Gary Shteyngart. But first, check out these exclusive readings and excerpts from their debut novels.

What We Lose (Viking, July) by Zinzi Clemmons

Salt Houses (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, May) by Hala Alyan

Large Animals (Catapult, May) by Jess Arndt

The Leavers (Algonquin Books, May) by Lisa Ko

The Windfall (Crown, June) by Diksha Basu

What We Lose

by Zinzi Clemmons

My parents’ bedroom is arranged exactly the same as it always was. The big mahogany dresser sits opposite the bed, the doily still in place on the vanity. My mother’s little ring holders and perfume bottles still stand there. On top of all these old feminine relics, my father has set up his home office. His old IBM laptop sits atop the doily, a tangle of cords choking my mother’s silver makeup tray. His books are scattered around the tables, his clothes draped carelessly over the antique wing chair that my mother found on a trip to Quebec.

In the kitchen, my father switches on a small flat-screen TV that he’s installed on the wall opposite the stove. My mother never allowed TV in the kitchen, to encourage bonding during family dinners and focus during homework time. As a matter of fact, we never had more than one television while I was growing up—an old wood-paneled set that lived in the cold basement, carefully hidden from me and visitors in the main living areas of the house.

We order Chinese from the place around the corner, the same order that we’ve made for years: sesame chicken, vegetable fried rice, shrimp lo mein. As soon as they hear my father’s voice on the line, they put in the order; he doesn’t even have to ask for it. When he picks the order up, they ask after me. When my mother died, they started giving us extra sodas with our order, and he returns with two cans of pineapple soda, my favorite.

My father tells me that he’s been organizing at work, now that he’s the only black faculty member in the upper ranks of the administration.

I notice that he has started cutting his hair differently. It is shorter on the sides and disappearing in patches around the crown of his skull. He pulls himself up in his chair with noticeable effort. He had barely aged in the past twenty years, and suddenly, in the past year, he has inched closer to looking like his father, a stooped, lean, yellow-skinned man I’ve only seen in pictures.

“How have you been, Dad?” I say as we sit at the table.

The thought of losing my father lurks constantly in my mind now, shadowy, inexpressible, but bursting to the surface when, like now, I perceive the limits of his body. Something catches in my throat and I clench my jaw.

My father says that he has been keeping busy. He has been volunteering every month at the community garden on Christian Street, turning compost and watering kale.

“And I’m starting a petition to hire another black professor,” he says, stabbing his glazed chicken with a fire I haven’t seen in him in years.

He asks about Peter.

“I’m glad you’ve found someone you like,” he says.

“Love, Dad,” I say. “We’re in love.”

He pauses, stirring his noodles quizzically with his fork. “Why aren’t you eating?” he asks.

I stare at the food in front of me. It’s the closest thing to comfort food since my mother has been gone. The unique flavor of her curries and stews buried, forever, with her. The sight of the food appeals to me, but the smell, suddenly, is noxious; the wisp of steam emanating from it, scorching.

“Are you all right?”

All of a sudden, I have the feeling that I am sinking. I feel the pressure of my skin holding in my organs and blood vessels and fluids; the tickle of every hair that covers it. The feeling is so disorienting and overwhelming that I can no longer hold my head up. I push my dinner away from me. I walk calmly but quickly to the powder room, lift the toilet seat, and throw up.

From What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons, published in July by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Zinzi Clemmons.

(Photo: Nina Subin)Salt Houses

by Hala Alyan

On the street, she fumbles for a cigarette from her purse and smokes as she walks into the evening. She feels a sudden urge, now that she is outside the apartment, to clear her head. This is her favorite thing about the city—the ability it gives you to walk, to literally put space between your body and distress. In Kuwait, nobody walks anywhere.

Mimi lives in a quiet part of the city, mostly residential, with small, pretty apartments, each window like a glistening eye. The streetlamps are made of wrought iron, designs flanking either side of the bulbs. There is a minimalist sense of wealth in the neighborhood, children dressed simply, the women always adjusting scarves around their necks, their hair cut into perfectly symmetrical lines. Souad walks by the manicured lawns of a grammar school, empty and discarded for the summer. Next to it a gray-steepled church. She tries to imagine that, elsewhere, there is smoke and destroyed palaces and men carrying guns. It seems impossible.

The night is cool, and Souad wraps her cardigan tightly around her, crosses her arms. A shiver runs through her. She is nervous to see him, a familiar thrill that he always elicits in her. Even before last night.

Le Chat Rouge is a fifteen-minute walk from Mimi’s apartment, but within several blocks the streets begin to change, brownstones and Gothic-style latticework replaced with grungier alleyways, young Algerian men with long hair sitting on steps and drinking beer from cans. One eyes her and calls out, caressingly, something in French. She can make out the words for sweet and return. Bars line the streets with their neon signs and she walks directly across the Quartier Latin courtyard, her shoes clicking on the cobblestones.

“My mother’s going to call tomorrow,” she told Elie yesterday. She wasn’t sure why she said it, but it felt necessary. “They’re taking me to Amman.” In the near dark, Elie’s face was peculiarly lit, the sign making his skin look alien.

“You could stay here,” Elie said. He smiled mockingly. “You could get married.”

Souad had blinked, her lips still wet from the kiss. “Married?” She wasn’t being coy—she truthfully had no idea what Elie meant. Married to whom? For a long, awful moment, she thought Elie was suggesting she marry one of the other Lebanese men, that he was fobbing her off on a friend in pity.

“Yes.” Elie cocked his head, as though gauging the authenticity of her confusion. He smiled again, kinder this time. He closed his fingers around hers so that she was making a fist and he a larger one atop it. They both watched their hands silently for a few seconds, an awkward pose, more confrontational than romantic, as though he were preventing her from delivering a blow. It occurred to her that he was having a difficult time speaking. She felt her palm itch but didn’t move. Elie cleared his throat, and when he spoke, she had to lean in to hear him.

“You could marry me.”

Now, even in re-creating that moment, Souad feels the swoop in her stomach, her mouth drying. It is a thing she wants in the darkest, most furtive way, not realizing how badly until it was said aloud. Eighteen years old, a voice within her spoke, eighteen. Too young, too young. And her parents, her waiting life.

But the greater, arrogant part of Souad’s self growled as if woken. Her steps clacked with her want of it. The self swelled triumphantly—Shame, shame, she admonishes herself, thinking of the war, the invasion, the troops and fire, but she is delighted nonetheless.

From Salt Houses by Hala Alyan. Copyright © 2017 by Hala Alyan. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

(Photo: Beowulf Sheehan)Large Animals

by Jess Arndt

In my sleep I was plagued by large animals—teams of grizzlies, timber wolves, gorillas even came in and out of the mist. Once the now extinct northern white rhino also stopped by. But none of them came as often or with such a ferocious sexual charge as what I, mangling Latin and English as usual, called the Walri. Lying there, I faced them as you would the inevitable. They were massive, tube-shaped, sometimes the feeling was only flesh and I couldn’t see the top of the cylinder that masqueraded as a head or tusks or eyes. Nonetheless I knew I was in their presence intuitively. There was no mistaking their skin; their smell was unmistakable too, as was their awful weight.

During these nights (the days seemed to disappear before they even started) I was living two miles from a military testing site. In the early morning and throughout the day the soft, dense sound of bombs filled the valley. It was comforting somehow. Otherwise I was entirely alone.

This seemed a precondition for the Walri—that I should be theirs and theirs only. on the rare occasion that I had an overnight visitor to my desert bungalow the Walri were never around. Then the bears would return in force, maybe even a large local animal like a mountain lion or goat, but no form’s density came close to walrusness. So I became wary and stopped inviting anyone out to visit at all.

The days, unmemorable, had a kind of habitual slide. I would wake up with the sun and begin cleaning the house. No matter how tightly I’d kept the doors shut the day before, dust and sand and even large pieces of mineral rock seemed to shove their way inside. I swept these into piles. Then the dishes that I barely remembered dirtying—some mornings it was as if the whole artillery of pots and pans had been used in the night by someone else—then the trash (again always full), then some coffee. Eight o’clock.

This work done, I sat in various chairs in the house following the bright but pale blades of light. I was drying out. oh, an LA friend said somewhat knowingly, from the booze? But I had alcohol with me, plenty of it. It wasn’t that. I moved as if preprogrammed. only later did I realize that my sleep was so soggy that it took strong desert sun to unshrivel me and since it was the middle of winter and the beams were perforce slanted, I’d take all of it I could find.

For lunch I got in my car and drove into town, to the empty parking lot of Las Palmas. There were many Mexican joints along the highway that also functioned as Main Street. I hadn’t bothered to try them out. Las Palmas, with its vacant booths, dusty cacti, and combination platter lunch special for $11.99 including $4 house margarita, was fine.

A waitress named Tamara worked there. She seemed like the only one. She wasn’t my type—so tall she bent over herself and a bona fide chain-smoker. Sometimes to order you’d have to exit your booth and find her puffing outside. A friend who had borrowed the bungalow before I did told me about Tamara and so if I had a crush at all it was an inherited one that even came with inherited guilt—from having taken her on once he could no longer visit her. Regardless, we barely spoke.

I had things I was supposed to be doing, more work than I could accomplish even if I

duct-taped my fists to my laptop, but none of it seemed relevant to my current state. In the afternoons I drove back home slowly, always stopping for six-packs of beer at the Circle K. I enjoyed the task. The beer evaporated once I stuck it in my fridge—it was there and then, it was gone.

My sleeping area was simple: a bed on a plywood platform. A wooden dresser. Built-in closets and a cement floor. At first I would wake up in the night from the sheer flattening silence of the desert. It was impossible that the world still existed elsewhere. After that initial jolt, relief.

Don’t you miss it? my same friend said during our weekly telephone chats. But I couldn’t explain the euphoria of walking up and down the chilly aisles of Stater Bros. In week-old sweatpants if I wanted, uncounted by life. Would I buy refried or whole beans? This brand or that? It didn’t matter, no one cared.

It was in these conditions that the Walri arrived.

* * *

I’d slept as usual for the first few hours, heavily, in a kind of coma state. Then had woken, I thought to pee. But lying there with the gritty sheets braided around me, the violet light that was created from the fly zapper, the desert cold that was entering through the gaps and cracks in the fire’s absence—I felt a new form of suffocation.

It wasn’t supernatural. I’d also had that. The sense of someone’s vast weight sitting on the bed with you or patting your body with ghostly hands. This breathless feeling was larger, as if I was uniformly surrounded by mammoth flesh.

Dream parts snagged at me. Slapping sounds and hose-like alien respiration. I felt I was wrestling within inches of what must be—since I couldn’t breathe—the end of my life. Now the lens of my dream panned backward and I saw my opponent in his entirety.

He lay (if that’s what you could call it) on my bed, thick and wrinkled, the creases in his hide so deep I could stick my arms between them. His teeth were yellow and as long as my legs.

“I’m sexually dormant,” I said aloud to him. “But I want to put my balls in someone’s face.”

Then somehow light was peeling everything back for dawn.

From Large Animals. Used with permission of Catapult. Copyright 2017 by Jess Arndt.

(Photo: Johanna Breiding)The Leavers

by Lisa Ko

The day before Deming Guo saw his mother for the last time, she surprised him at school. A navy blue hat sat low on her forehead, scarf around her neck like a big brown snake. “What are you waiting for, Kid? It’s cold out.”

He stood in the doorway of P.S. 33 as she zipped his coat so hard the collar pinched. “Did you get off work early?” It was four thirty, already dark, but she didn’t usually leave the nail salon until six.

They spoke, as always, in Fuzhounese. “Short shift. Michael said you had to stay late to get help on an assignment.” Her eyes narrowed behind her glasses, and he couldn’t tell if she bought it or not. Teachers didn’t call your mom when you got detention, only gave a form you had to return with a signature, which he forged. Michael, who never got detention, had left after eighth period, and Deming wanted to get back home with him, in front of the television, where, in the safety of a laugh track, he didn’t have to worry about letting anyone down.

Snow fell like clots of wet laundry. Deming and his mother walked up Jerome Avenue. In the back of a concrete courtyard three older boys were passing a blunt, coats unzipped, wearing neither backpacks nor hats, sweet smoke and slow laughter warming the thin February air. “I don’t want you to be like that,” she said. “I don’t want you to be like me. I didn’t even finish eighth grade.”

What a sweet idea, not finishing eighth grade. He could barely finish fifth. His teachers said it was an issue of focus, of not applying himself. Yet when he tripped Travis Bhopa in math class Deming had been as shocked as Travis was. “I’ll come to your school tomorrow,” his mother said, “talk to your teacher about that assignment.” He kept his arm against his mother’s, loved the scratchy sound of their jackets rubbing together. She wasn’t one of those TV moms, always hugging their kids or watching them with bemused smiles, but insisted on holding his hand when they crossed a busy street. Inside her gloves her hands were red and scraped, the skin angry and peeling, and every night before she went to sleep she rubbed a thick lotion onto her fingers and winced. Once he asked if it made them hurt less. She said only for a little while, and he wished there was a special lotion that could make new skin grow, a pair of superpower gloves.

Short and blocky, she wore loose jeans—never had he seen her in a dress—and her voice was so loud that when she called his name dogs would bark and other kids jerked around. When she saw his last report card he thought her shouting would set off the car alarms four stories below. But her laughter was as loud as her shouting, and there was no better, more gratifying sound than when she slapped her knees and cackled at something silly. She laughed at things that weren’t meant to be funny, like TV dramas and the swollen orchestral soundtracks that accompanied them, or, better yet, at things Deming said, like when he nailed the way their neighbor Tommie always went, “Not bad-not bad-not bad” when they passed him in the stairwell, an automatic response to a “Hello-how-are-you” that hadn’t yet been issued. Or the time she’d asked, flipping through TV stations, “Dancing with the Stars isn’t on?” and he had excavated Michael’s old paper mobile of the solar system and waltzed with it through the living room as she clapped. It was almost as good as getting cheered on by his friends.

When he had lived in Minjiang with his grandfather, Deming’s mother had explored New York by herself. There was a restlessness to her, an inability to be still or settled. She jiggled her legs, bounced her knees, cracked her knuckles, twirled her thumbs. She hated being cooped up in the apartment on a sunny day, paced the rooms from wall to wall to wall, a cigarette dangling from her mouth. “Who wants to go for a walk?” she would say. Her boyfriend Leon would tell her to relax, sit down. “Sit down? We’ve been sitting all day!” Deming would want to stay on the couch with Michael, but he couldn’t say no to her and they’d go out, no family but each other. He would have her to himself, an ambling walk in the park or along the river, making up stories about who lived in the apartments they saw from the outside—a family named Smith, five kids, father dead, mother addicted to bagels, he speculated the day they went to the Upper East Side. “To bagels?” she said. “What flavor bagel?” “Everything bagels,” he said, which made her giggle harder, until they were both bent over on Madison Avenue, laughing so hard no sounds were coming out, and his stomach hurt but he couldn’t stop laughing, old white people giving them stink eye for stopping in the middle of the sidewalk. Deming and his mother loved everything bagels, the sheer balls of it, the New York audacity that a bagel could proclaim to be everything, even if it was only topped with sesame seeds and poppy seeds and salt.

A bus lumbered past, spraying slush. The walk sign flashed on. “You know what I did today?” his mother said. “One lady, she had a callus the size of your nose on her heel. I had to scrape all that dead skin off. It took forever. And her tip was shit. You’ll never do that, if you’re careful.”

He dreaded this familiar refrain. His mother could curse, but the one time he’d let motherfucker bounce out in front of her, loving the way the syllables got meatbally in his mouth, she had slapped his arm and said he was better than that. Now he silently said the word to himself as he walked, one syllable per footstep.

“Did you think that when I was growing up, a small girl your age, I thought: hey, one day, I’m going to come all the way to New York so I can pick gao gao out of a stranger’s toe? That was not my plan.”

Always be prepared, she liked to say. Never rely on anyone else to give you things you could get yourself. She despised laziness, softness, people who were weak. She had few friends, but was true to the ones she had. She could hold a fierce grudge, would walk an extra three blocks to another grocery store because, two years ago, a cashier at the one around the corner had smirked at her lousy English. It was lousy, Deming agreed.

From The Leavers. Printed by permission of Algonquin Books. Copyright © 2017 by Lisa Ko.

(Photo: Bartosz Potocki)The Windfall

by Diksha Basu

The following week, on an unusually overcast September day, Mr. Jha pulled into the quiet lane of his new Gurgaon home. He had never been here by himself, he realized. Mrs. Jha was usually with him, and this summer Rupak had come with them a few times, and there were all the contractors and painters and builders buzzing around, working. He had never really appreciated the silence and the greenery before. Gurgaon felt still while the rest of Delhi throbbed.

The air was heavy with heat and the promise of rain. On the radio, a Bon Jovi song played. “It’s been raining since you left me,” the lyrics said. How funny, Mr. Jha thought. An Indian song would have to say, “It hasn’t rained since you left me.” Unless, of course, you were happy that they left you.

An electronic shoe-polishing machine in a large box was on the passenger seat of his Mercedes. He had strapped it in with the seat belt. It was beautiful. And it was expensive. It was not a planned purchase. This morning he had a breakfast meeting with two young men who were launching a website that would help you find handymen around Delhi, and they asked him to join their team as a consultant. He declined. He did not have time to take on any new work until they were done moving homes. And then they had to visit Rupak, so he was not going to have any free time until November or December. And then it would be the holiday season, so really it was best if he took the rest of the year off work.

The meeting was over breakfast at the luxurious Teresa’s Hotel in Connaught Place in central Delhi, and after filling himself up with mini croissants, fruit tarts, sliced cheeses, salami, coffee, and orange juice, Mr. Jha went for a stroll through the lobby and the other restaurants in the hotel. All the five-star hotels in the center of town were little oases of calm and cool. Mr. Jha was walking by the large windows that overlooked the swimming pool that was for guests only when he thought he would book a two-night stay here. He knew his wife loved the indulgence of nice hotels and he had recently read about what youngsters were calling a staycation—a vacation where you don’t leave the city or the home you usually live in, but you give yourself a few days to take a holiday. Of course, since he didn’t work much anymore, most days, weeks, months were a staycation, but how wonderful it would be to check into a hotel and have a lazy few days. Having room service—or, like they were called at Teresa’s, butlers—was a different sort of pleasure than having servants bringing you food and cleaning your home. Butlers showed that you had made the progression from servants to expensive appliances to uniformed men who ran the expensive appliances.

From The Windfall, published by Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, in June. Copyright © 2017 by Diksha Basu.

(Photo: Mikey McCleary)

For our sixteenth annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five established authors to introduce this year’s group of debut writers. Read the July/August 2016 issue of the magazine for interviews between Yaa Gyasi and Angela Flournoy, Masande Ntshanga and Naomi Jackson, Rumaan Alam and Emma Straub, Maryse Meijer and Lindsay Hunter, and Imbolo Mbue and Christina Baker Kline. But first, check out these exclusive readings and excerpts from their debut novels.

Homegoing (Knopf, June) by Yaa Gyasi

The Reactive (Two Dollar Radio, June) by Masande Ntshanga

Rich and Pretty (Ecco, June) by Rumaan Alam

Heartbreaker (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, July) by Maryse Meijer

Behold the Dreamers (Random House, August) by Imbolo Mbue

The night Effia Otcher was born into the musky heat of Fanteland, a fire raged through the woods just outside her father’s compound. It moved quickly, tearing a path for days. It lived off the air; it slept in caves and hid in trees; it burned, up and through, unconcerned with what wreckage it left behind, until it reached an Asante village. There, it disappeared, becoming one with the night.

Effia’s father, Cobbe Otcher, left his first wife, Baaba, with the new baby so that he might survey the damage to his yams, that most precious crop known far and wide to sustain families. Cobbe had lost seven yams, and he felt each loss as a blow to his own family. He knew then that the memory of the fire that burned, then fled, would haunt him, his children, and his children’s children for as long as the line continued. When he came back into Baaba’s hut to find Effia, the child of the night’s fire, shrieking into the air, he looked at his wife and said, “We will never again speak of what happened today.”

The villagers began to say that the baby was born of the fire, that this was the reason Baaba had no milk. Effia was nursed by Cobbe’s second wife, who had just given birth to a son three months before. Effia would not latch on, and when she did, her sharp gums would tear at the flesh around the woman’s nipples until she became afraid to feed the baby. Because of this, Effia grew thinner, skin on small bird- like bones, with a large black hole of a mouth that expelled a hungry crywhich could be heard throughout the village, even on the days Baaba did her best to smother it, covering the baby’s lips with the rough palm of her left hand.

“Love her,” Cobbe commanded, as though love were as simple an act as lifting food up from an iron plate and past one’s lips. At night, Baaba dreamed of leaving the baby in the dark forest so that the god Nyame could do with her as he pleased.

Effia grew older. The summer after her third birthday, Baaba had her first son. The boy’s name was Fiifi, and he was so fat that some- times, when Baaba wasn’t looking, Effia would roll him along the ground like a ball. The first day that Baaba let Effia hold him, she accidentally dropped him. The baby bounced on his buttocks, landed on his stomach, and looked up at everyone in the room, confused as to whether or not he should cry. He decided against it, but Baaba, who had been stirring banku, lifted her stirring stick and beat Effia across her bare back. Each time the stick lifted off the girl’s body, it would leave behind hot, sticky pieces of banku that burned into her flesh. By the time Baaba had finished, Effia was covered with sores, screaming and crying. From the floor, rolling this way and that on his belly, Fiifi looked at Effia with his saucer eyes but made no noise.

Cobbe came home to find his other wives attending to Effia’s wounds and understood immediately what had happened. He and Baaba fought well into the night. Effia could hear them through the thin walls of the hut where she lay on the floor, drifting in and out of a feverish sleep. In her dream, Cobbe was a lion and Baaba was a tree. The lion plucked the tree from the ground where it stood and slammed it back down. The tree stretched its branches in protest, and the lion ripped them off, one by one. The tree, horizontal, began to cry red ants that traveled down the thin cracks between its bark. The ants pooled on the soft earth around the top of the tree trunk.

And so the cycle began. Baaba beat Effia. Cobbe beat Baaba. By the time Effia had reached age ten, she could recite a history of the scars on her body. The summer of 1764, when Baaba broke yams across her back. The spring of 1767, when Baaba bashed her left foot with a rock, breaking her big toe so that it now always pointed away from the other toes. For each scar on Effia’s body, there was a companion scar on Baaba’ s, but that didn’t stop mother from beating daughter, father from beating mother.

Matters were only made worse by Effia’s blossoming beauty. When she was twelve, her breasts arrived, two lumps that sprung from her chest, as soft as mango flesh. The men of the village knew that first blood would soon follow, and they waited for the chance to ask Baaba and Cobbe for her hand. The gifts started. One man tapped palm wine better than anyone else in the village, but another’s fishing nets were never empty. Cobbe’s family feasted off Effia’s burgeoning woman- hood. Their bellies, their hands, were never empty.

Excerpted from HOMEGOING by Yaa Gyasi. Copyright © 2016 by Yaa Gyasi. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

The Reactive

By Masande Ntshanga

The way I got to know them, by the way, my two closest friends here, is that we met at one of the new HIV and drug-counseling sessions cropping up all over the city. We were in the basement parking lot of the free clinic in Wynberg. The seminar room upstairs had been locked up and taped shut, there’d been a mercury spill, and our group couldn’t meet in there on account of the vapors being toxic to human tissue. Instead, they arranged us in the basement parking lot, and in two weeks we got used to not being sent upstairs for meetings. I did, in any case, and that was enough for me in the beginning.

In those days, I attended the meetings alone. I’d catch a taxi from Obs over to Wynberg for an afternoon’s worth of counseling. By the end of my first month, when the seminar room had been swept once, and then twice, and then three times by a short man who wore a blue contamination meter over his chest, each time checking out clean, everyone decided they preferred it down below, and so that’s where we stayed.

Maybe we all want to be buried here, I said.

It had been the first time I’d spoken in group. Talking always took me a while, back then, but the remark succeeded in making a few of them laugh. It won me chuckles even from the old-timers, and later, I wrote down my first addiction story to share with the group. It was from a film I saw adapted from a book I wasn’t likely to read. Ruan and Cissie arrived on the following Wednesday.

I noticed them immediately. Something seemed to draw us in from our first meeting. In the parking lot, we eyeballed each other for a while before we spoke. During the coffee break, we stood by the serving table in front of a peeling Toyota bakkie, mumbling tentatively towards each other’s profiles. I learned that Cecelia was a teacher. She pulled week-long shifts at a daycare center just off Bridge Street in Mowbray, and she was there on account of the school’s accepting its first openly positive pupil. Ruan, who was leaning against the plastic table, gulping more than sipping at the coffee in his paper cup, said that he suffocated through his life by working on the top floor of his uncle’s computer firm. He was there to shop for a social issue they could use for their corporate responsibility strategy. He called it CRS, and Cissie and I had to ask him what he meant.

In the end, I guess I was impressed. I told them how I used to be a lab assistant at Peninsula Tech, and how in a way this was part of how I’d got to be sick with what I have.

When we sat back down again, we listened to the rest of the members assess each other’s nightmares. They passed them around with a familiar casualness. Mark knew about Ronelle’s school fees, for instance, and she knew about Linette’s hepatitis, and all of us knew that Linda had developed a spate of genital warts over September. She called them water warts, when she first told us, and, like most of her symptoms, she blamed them on the rain.

That day, when the discussion turned to drug abuse, as it always did during the last half-hour of our sessions, the three of us had nothing to add. I looked over at Ruan and caught him stashing a grin behind his fist, while on my other side, Cecelia blinked up at the ceiling. I didn’t need any more evidence for our kinship.

The meeting lasted the full two hours, and when it came to an end, I collected my proof of attendance and exchanged numbers with Ruan and Cecelia. I suppose we said our goodbyes at the entrance of the parking lot that day, and later, within that same week I think, we were huffing paint thinner together in my flat in Obs.

Excerpted from The Reactive by Masande Ntshanga. Copyright © 2016 by Masande Ntshanga. Excerpted by permission of Two Dollar Radio. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Rich and Pretty

By Rumaan Alam

Lauren’s office is freezing. You could keep butter on the desk. You could perform surgery. Every woman in the office—they’re all women—keeps a cashmere sweater on the back of her chair. They sit, hands outstretched over computer keyboards like a bum’s over a flaming garbage can. The usual office noises: typing, telephones, people using indoor voices, the double ding of an elevator going down. For some reason, the double ding of the elevator going down is louder than the single ding of the elevator going up. There’s a metaphor in there, waiting to be untangled. They make cookbooks, these women. There’s no food, just stacks of paper and editorial assistants in glasses. She’s worked here for four years. It’s fine.

Today is different because today there’s a guy, an actual dude, in the office with them, not a photographer or stylist popping by for a meeting, as does happen: He’s

a temp, because Kristen is having a baby and her doctor put her on bed rest. Lauren isn’t totally clear on what Kristen does, but now there’s a dude doing it. He’s wearing a button-down shirt and jeans, and loafers, not sneakers, which implies a certain maturity. Lauren’s been trying to get him to notice her all day. She’s the second-prettiest woman in the office, so it isn’t hard. Hannah, the prettiest, has a vacant quality about her. She’s not stupid, exactly—in fact, she’s very competent—but she doesn’t have spark. She’s not interesting, just thin and blond, with heavy eyeglasses and a photograph of her French bulldog on her computer screen.

Lauren has it all planned out. She’ll walk past his desk a couple of times, which isn’t suspicious because his desk isn’t far from the kitchen, and the kitchen is where the coffee is, and by the third time, he’ll follow her in there, and she’ll make a wisecrack about the coffee, and he’ll say it’s not so bad, and they’ll talk, and exchange phone numbers, e-mail addresses, whatever, and then later they’ll leave the office at the same time, ride down together in the elevator and not talk because they both understand that the social contract dictates that sane people do not talk in elevators, and then he’ll let her go through the revolving door first, even though she’s pretty sure that etiquette has it that men precede women through revolving doors, and then they’ll both be standing on Broadway, and there will be traffic and that vague smell of charred, ethnic meat from the guy with the lunch cart on the corner, and he’ll suggest they get a drink, and she’ll say sure, and they’ll go to the Irish pub on Fifty-Fifth Street, because there’s nowhere else to go, and after two drinks they’ll be starving, and he’ll suggest they get dinner, but there’s nowhere to eat in this part of town, so they’ll take the train to Union Square and realize there’s nowhere to eat there either, and they’ll walk down into the East Village and find something, maybe ramen, or that Moroccan-y place that she always forgets she likes, and they’ll eat, and they’ll start touching each other, casually but deliberately, carefully, and the check will come and she’ll say let’s split it, and he’ll say no let me, even though he’s a temp and can’t make that much money, right? Then they’ll be drunk, so taking a cab seems wise and they’ll make out in the backseat, but just a little bit, and kind of laugh about it, too: stop to check their phones, or admire the view, or so he can explain that he lives with a roommate or a dog, or so she can tell him some stupid story about work that won’t mean anything to him anyway because it’s only his first day and he doesn’t know anyone’s name, let alone their personality quirks and the complexities of the office’s political and social ecosystem.

Then he’ll pay the driver, because they’ll go to his place—she doesn’t want to bring the temp back to her place—and it’ll be nice, or fine, or ugly, and he’ll open beers because all he has are beers, and she’ll pretend to drink hers even though she’s had enough, and he’ll excuse himself for a minute to go to the bathroom, but really it’s to brush his teeth, piss, maybe rub some wet toilet paper around his ass and under his balls. This is something Gabe had told her, years ago, that men do this, or at least, that he did. Unerotic, but somehow touching. Then the temp will come sit next to her on the couch, please let it be a couch and not a futon, and he’ll play with her hair a little before he kisses her, his mouth minty, hers beery. He’ll be out of his shirt, then, and he’s hard and hairy, but also a little soft at the belly, which she likes. She once slept with this guy Sean, whose torso, hairless and lean, freaked her out. It was like having sex with a female mannequin. The temp will push or pull her into his bedroom, just the right balance of aggression and respect, and the room will be fine, or ugly, and the bedsheets will be navy, as men’s bedsheets always are, and there will be venetian blinds, and lots of books on the nightstand because he’s temping at a publishing company so he must love to read. She’ll tug her shirt over her head, and he’ll pull at her bra, and they’ll be naked, and he’ll fumble around for a condom, and his dick will be long but not, crucially, thick, and it will be good, and then it will be over. They’ll laugh about how this whole thing is against the company’s sexual harassment policy. She’ll try to cover herself with the sheet, and he’ll do the same, suddenly embarrassed by his smaller, slightly sticky dick. When he’s out of the room, to get a beer, to piss, whatever, she’ll get dressed. He’ll call her a car service, because there are no yellow cabs wherever he lives. They’ll both spend the part of the night right before they fall asleep trying to figure out how to act around each other in the office tomorrow.

Or maybe not that. Maybe she’ll find a way to go up to him and say, what, exactly, Hey, do you like parties? Do you want to go to a party . . . tonight? No, the jeans and tie are fine. It’s not fancy. A party. A good party. Good open bar, for sure. Probably canapés, what are canapés exactly, whatever they are, there will probably be some. Last party, there were these balls of cornbread and shrimp, like deep fried, holy shit they were great. That was last year, I think. Anyway, there might be celebrities there. There will definitely be celebrities there. I once saw Bill Clinton at one of these parties. He’s skinnier than you’d think. Anyway, think about it, it’ll be a time, and by the way, I’m Lauren, I’m an associate editor here and you are? She can picture his conversation, the words coming to her so easily, as they do in fantasy but never in reality. They call it meeting cute, in movies, but it only happens in movies.

From Rich and Pretty by Rumaan Alam. Copyright © 2016 by Rumaan Alam. Excerpted by permission of Ecco, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Heartbreaker

By Maryse Meijer

Daddy comes over on Thursdays. My husband and son are out watching movies where people blow each other up. They have burgers afterward and buf- falo wings and milkshakes and they talk about TV shows and girls and the latest bloody video game. At least that’s what I imagine they do. No way do they imagine what I am doing, sitting here at the kitchen table doing my math homework as Daddy microwaves the mac and cheese he brought over. We have three hours together and in these three hours I am twelve years old and my daddy is the most wonderful man in the world.

On craigslist I post the photo from my work website, the one with my hair scraped back in a ponytail, expos- ing my shiny forehead, my thin lips, my arms bursting from the sleeves of my blue blouse. Daughter seeks Father is all I write as a caption. In response I receive an avalanche of cell-phone numbers, chat invitations, and penis pics lifted from porn sites.

I delete all the emails except for Richard’s: Sweetheart, please call home. I sit for a moment hunched in my cubicle, sweating, before lifting the receiver and dialing his number.

Daddy? I whisper, hand up to cover my mouth so no one walking by can see it moving.

He doesn’t skip a beat. Sweetheart! he says. Did you see the photo? I ask.

Of course, he says.

I’m not better in person, I warn. You’re perfect, he assures me.

I’m married, I tell him. I have a kid. No problem, he insists.

I chew the inside of my cheek. There’s not going to be any sex, I say.

Absolutely not! he agrees.

I wait for him to say something creepy or disgusting, but he doesn’t. We make arrangements to meet at McDonald’s for dinner on Thursday.

Don’t kill me, I say, and he laughs.

Oh sweetheart, he says. What on earth?

I’m early. I don’t know what Daddy looks like and every time the door swings open my head jerks like a ball on a string. I convince myself I’m going to be stood up and that it will be better anyway if I am. But at seven on the dot he enters and he looks straight at me and waves.

Our usual, sweetheart? he says, loud enough for other people to hear, and I nod. He brings a tray of chicken nugget combos to my table. He kisses my cheek. The food steams in our hands as we look at each other; he seems about twenty, twenty-two, with chinos frayed at the bottoms and red hair and glasses and biceps as skinny as my wrist. Maybe someday he will be good- looking.

Extra barbecue sauce, just the way you like, he says, gesturing to my nuggets. I smile and take a bite. He asks me about school and I ask him about work and he is as interested in how I’m doing in gym class as I am in the stocks he’s trading at the office; we slip into our new roles as easily as knives into butter.

I almost forgot, he says. He reaches into the pocket of his jacket and pulls out a CD with a Christmas bow stuck on it. Just a little something, he adds, and hands it to me. I unstick the bow and turn the CD over in my hands: Britney Spears. I bounce, once, and my left butt cheek, which doesn’t quite fit on the plastic chair, bangs on the edge of the seat.

Oh Daddy, I say, touched because I k now he went into a store and asked what would be the right thing to get for his little girl, and he paid for it with his own money and put it in his pocket and found the gaudy bow to go with it and then brought it all the way here, to me, because he k new he would like me and already wanted to give me something, and this makes me want to give everything I have to him in return.

Apart from Thursday nights—and it’s always Thurs- days, always nights—we don’t communicate, except by email. Sometimes he’ll send me a note just to say, Have a great day!! or he’ll tell me what plans he has for dinner: Working late need a treat pizza sound good??? or he’ll hint at imagined happenings in my little-girl life: Don’t forget dentist today xoxoxoxo!! and Good luck on the history quiz I know you’ll do awesome!!!! I write back in equally breathless terms to report the results of the history quiz or the number of cavities rotting my teeth or to squeal over the impending pizza feast. These exchanges give me a high so intense my chest muscles spasm and when my boss calls and says to bring her such-and-such a document I hit print and out comes an email from Daddy, not the work document, and I giggle into my hand and hit print again.

He always arrives exactly fifteen minutes after my hus- band and son leave. I sit on the couch with the televi- sion on while he fumbles with the keys and the empty banged-up briefcase he always brings. Sweetheart! he says when he enters, and I yelp Daddy! and if I was maybe ten or twenty or, okay, thirty pounds lighter, I might run toward him, but as it is I wait on the couch for him to come over and k iss my hair. I’ll pour him a soda on the rocks and he’ll pour me some milk and we touch glasses and smile. If my husband calls I stand by the back door with my head down and say Uh-huh, yes, fine, all right, see you soon, no, nothing for me, thanks, I’m enjoying the leftovers, have fun, love you.

Excerpted from Heartbreaker by Maryse Meijer. Copyright © Maryse Meijer, 2016. Reprinted with permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Behold the Dreamers

By Imbolo Mbue

He’d never been asked to wear a suit to a job interview. Never been told to bring along a copy of his résumé. He hadn’t even owned a résumé until the previous week when he’d gone to the library on Thirty-fourth and Madison and a volunteer career counselor had written one for him, detailed his work history to suggest he was a man of grand accomplishments: farmer responsible for tilling land and growing healthy crops; street cleaner responsible for making sure the town of Limbe looked beautiful and pristine; dishwasher in Manhattan restaurant, in charge of ensuring patrons ate from clean and germ-free plates; livery cabdriver in the Bronx, responsible for taking passengers safely from place to place.

He’d never had to worry about whether his experience would be appropriate, whether his English would be perfect, whether he would succeed in coming across as intelligent enough. But today, dressed in the green double-breasted pinstripe suit he’d worn the day he entered America, his ability to impress a man he’d never met was all he could think about. Try as he might, he could do nothing but think about the questions he might be asked, the answers he would need to give, the way he would have to walk and talk and sit, the times he would need to speak or listen and nod, the things he would have to say or not say, the response he would need to give if asked about his legal status in the country. His throat went dry. His palms moistened. Unable to reach for his handkerchief in the packed downtown subway, he wiped both palms on his pants.

“Good morning, please,” he said to the security guard in the lobby when he arrived at Lehman Brothers. “My name is Jende Jonga. I am here for Mr. Edwards. Mr. Clark Edwards.”

The guard, goateed and freckled, asked for his ID, which he quickly pulled out of his brown bifold wallet. The man took it, examined it front and back, looked up at his face, looked down at his suit, smiled, and asked if he was trying to become a stockbroker or something.

Jende shook his head. “No,” he replied without smiling back. “A chauffeur.”

“Right on,” the guard said as he handed him a visitor pass. “Good luck with that.”

This time Jende smiled. “Thank you, my brother,” he said. “I really need all that good luck today.”

Alone in the elevator to the twenty-eighth floor, he inspected his fingernails (no dirt, thankfully). He adjusted his clip-on tie using the security mirror above his head; reexamined his teeth and found no visible remnants of the fried ripe plantains and beans he’d eaten for breakfast. He cleared his throat and wiped off whatever saliva had crusted on the sides of his lips. When the doors opened he straightened his shoulders and introduced himself to the receptionist, who, after responding with a nod and a display of extraordinarily white teeth, made a phone call and asked him to follow her. They walked through an open space where young men in blue shirts sat in cubicles with multiple screens, down a corridor, past another open space of cluttered cubicles and into a sunny office with a four-paneled glass window running from wall to wall and floor to ceiling, the thousand autumn-drenched trees and proud towers of Manhattan standing outside. For a second his mouth fell open, at the view outside—the likes of which he’d never seen—and the exquisiteness inside. There was a lounging section (black leather sofa, two black leather chairs, glass coffee table) to his right, an executive desk (oval, cherry, black leather reclining chair for the executive, two green leather armchairs for visitors) in the center, and a wall unit (cherry, glass doors, white folders in neat rows) to his left, in front of which Clark Edwards, in a dark suit, was standing and feeding sheets of paper into a pullout shredder.

“Please, sir, good morning,” Jende said, turning toward him and half-bowing.

“Have a seat,” Clark said without lifting his eyes from the shredder.

Jende hurried to the armchair on the left. He pulled a résumé from his folder and placed it in front of Clark’s seat, careful not to disturb the layers of white papers and Wall Street Journals strewn across the desk in a jumble. One of the Journal pages, peeking from beneath sheets of numbers and graphs, had the headline: “Whites’ Great Hope? Barack Obama and the Dream of a Color-blind America.” Jende leaned forward to read the story, fascinated as he was by the young ambitious senator, but immediately sat upright when he remembered where he was, why he was there, what was about to happen.

“Do you have any outstanding tickets you need to resolve?” Clark asked as he sat down.

“No, sir,” Jende replied.

“And you haven’t been in any serious accidents, right?”

“No, Mr. Edwards.”

Clark picked up the résumé from his desk, wrinkled and moist like the man whose history it held. His eyes remained on it for several seconds while Jende’s darted back and forth, from the Central Park treetops far beyond the window to the office walls lined with abstract paintings and portraits of white men wearing bow ties. He could feel beads of sweat rising out of his forehead.

“Well, Jende,” Clark said, putting the résumé down and leaning back in his chair. “Tell me about yourself.”

Excerpted from Behold the Dreamers by Imbolo Mbue. Copyright © 2016 by Imbolo Mbue. Reprinted with permission of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

As part of our sixteenth annual First Fiction roundup, in which five debut authors—Yaa Gyasi, Masande Ntshanga, Rumaan Alam, Maryse Meijer, and Imbolo Mbue—discuss their first books, we picked nine more notable debuts that fans of fiction should consider reading this summer.

Remarkable (BOA Editions, May) by Dinah Cox

Set primarily in Oklahoma, the remarkable (that’s right, remarkable) stories in Cox’s award-winning collection spotlight characters whose wit, resilience, and pathos are as vast as the Great Plains landscape they inhabit.

Anatomy of a Soldier (Knopf, May) by Harry Parker

A former officer in the British Army who lost his legs in Afghanistan in 2009, Parker delivers a riveting, provocative novel that captures his wartime experience in an unconventional way. Forty-five inanimate objects—including a helmet, boots, and weapons—act as narrators, together offering the reader a powerful new perspective on war.

Goodnight, Beautiful Women (Grove, June) by Anna Noyes

With language both sensuous and precise, these interconnected stories immerse us in the lives of women and girls in coastal Maine as they navigate familial intimacy, sexual awakening, and love’s indiscretions.

Grief Is the Thing With Feathers (Graywolf, June) by Max Porter

In the wake of his wife’s sudden death, a man is visited by Crow, a “sentimental bird” that settles into the man’s life and the lives of his children in an attempt to heal the wounded family. A nuanced meditation that not only breaks open the boundaries of what constitutes a novel, but also demonstrates through its fragmentary form the unique challenge of writing about grief.

A Hundred Thousand Worlds (Viking, June) by Bob Proehl

Valerie and her son embark on a road trip from New York to Los Angeles to reunite the nine-year-old with his estranged father, attending comic-book conventions along the way. Proehl weaves the comic-con worlds of monsters and superheroes into a complex family saga, a tribute to a mother’s love and the way we tell stories that shape our lives.

Lily and the Octopus (Simon & Schuster, June)

by Steven Rowley

Rowley’s novel centers on narrator Ted Flask and his aging companion—a dachshund named Lily—but readers who mistake this as a simple “boy and his dog” story are in for a profound and pleasant surprise. This powerful debut is a touching exploration of friendship and grief.

Pond (Riverhead Books, July)

by Claire-Louise Bennett

In this compelling, innovative debut, the interior reality of an unnamed narrator—a solitary young woman living on the outskirts of a small coastal village—is revealed through the details of everyday life, some rendered in long stretches of narrative and others in poetic fragments. Bennett’s unique portrait of a persona emerges with an intensity and vision not often seen, or felt, in a debut.

Champion of the World (Putnam, July) by Chad Dundas

Gangsters, bootlegging, and fixed competitions converge in the tumultuous world of 1920s American wrestling, which disgraced former lightweight champion Pepper Van Dean and his wife, Moira, must navigate in order to create the life they want. With crisp, muscular prose, this 470-page historical novel illuminates a time of rapid change in America.

Problems (Emily Books, July) by Jade Sharma

Raw, unrepentant, and biting with dark humor, Problems turns the addiction-redemption narrative inside out, as Sharma follows heroin hobbyist Maya through her increasingly chaotic life after the end of both her marriage and an affair.

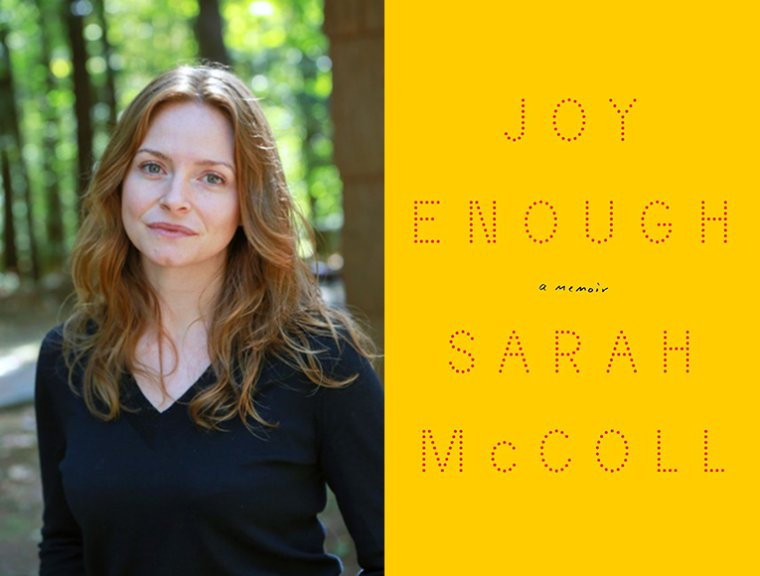

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Sarah McColl, whose memoir, Joy Enough, is out today from Liveright. “I loved my mother, and she died. Is that a story?” From the first sentences of her memoir, which Megan Stielstra calls “a stunningly beautiful and meditative map of loss,” McColl captures what it means to be a daughter. Through vivid memories, Joy Enough charts the dissolution of the author’s marriage alongside the impending loss of her mother, who is diagnosed with cancer. A book about love and grief, Joy Enough attempts to explain what people mean when they say, “You are just like your mother.” Sarah McColl was the founding editor in chief of Yahoo Food. A MacDowell fellow and Pushcart Prize nominee, her essays have appeared in the Paris Review, StoryQuarterly, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere. She holds an MFA from Sarah Lawrence and lives in Los Angeles.

1. How long did it take you to write Joy Enough?

For a long time I didn’t think I was writing a book. I thought I was writing essays, and then I was writing a thesis, and then I started thinking of it as my weird art project. I was so afraid to call it a book because I was afraid it wouldn’t be published, and then I would be a writer with an unpublished book in a drawer. Now I think at least one book in a drawer is a good thing. It means you’re doing the work. But I must have known there was something like a book there, whatever I called it, because I kept working on it, and I kept sending it out. That process of writing and revising took three years.

2. What was the most challenging thing about writing the book?

I didn’t know how to make memory conform to a narrative arc. There were discrete scenes and moments that were very vivid to me, but I struggled with how to connect one to another in some linear, continuous way. I remember expressing this frustration to one of my professors. She said, “Write the scene, hit return a few times, and keep going.” So that was my solution in the end. The return key.

3. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I participate with a group of writers in what we call “the 250s.” We have a shared Google doc with the days of the week marked out and a column for each writer. The goal is to write 250 words five days a week. The low word count is a mind trick to get you to sit down (it’s all about the mind tricks!) and then, hopefully, sail past 250 words. But if the writing is going badly, and you stop at 250, you still have some sense of accomplishment (again, mind trick). That’s the goal, mind you, and I do not consistently achieve this goal. Sometimes I walk around thinking about an essay for six months and then sit down and write a draft in one burst. I like the fuzzy, quiet quality of the mornings and the night. I have a small studio above the garage, but I also tend to write in bed a lot.

4. What was the most unexpected thing about the publication process?

I had no idea just how much buy-in a book requires. It’s not enough to have an agent champion a book and then for an editor to fall in love with it. The editor has to get everyone on board—sales, marketing, publicity. If your book finds a publisher, then it takes all those same people working on your behalf for a book to find its way in the world. Writing is such a solitary activity, but publishing is a completely different animal. I didn’t realize that at the outset. Sorry to get all “it takes a village,” but it really does, and I have pinched myself many times at how grateful I have felt in Liveright’s hands.

5. What are you reading right now?

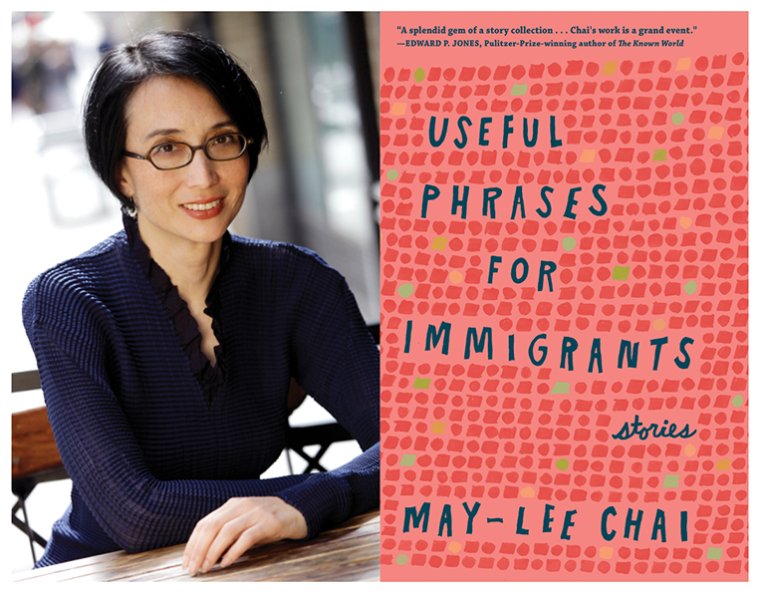

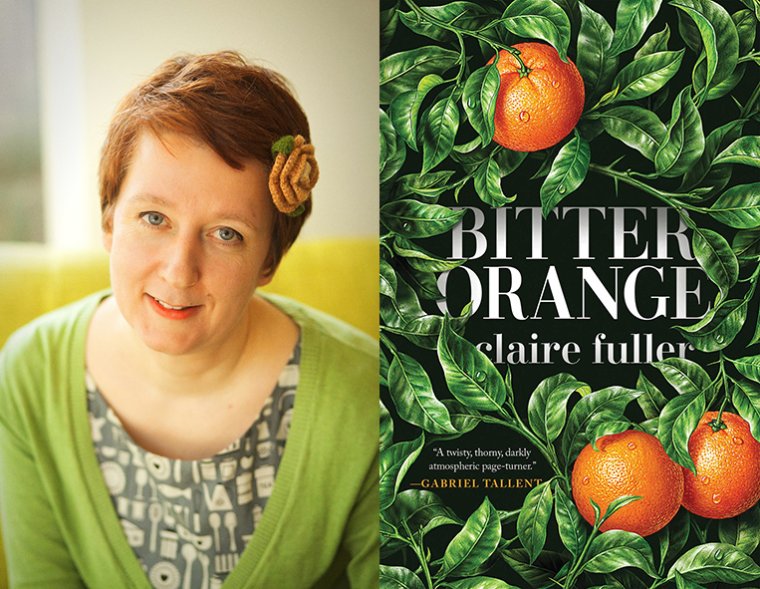

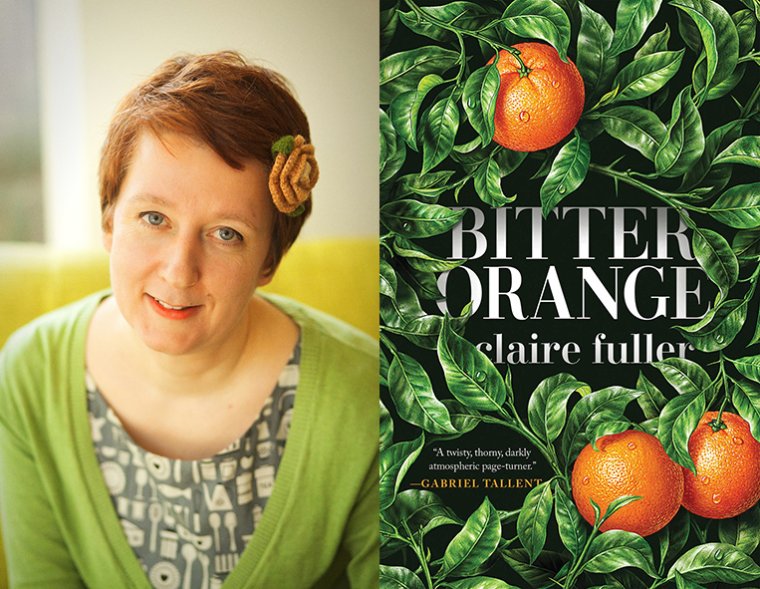

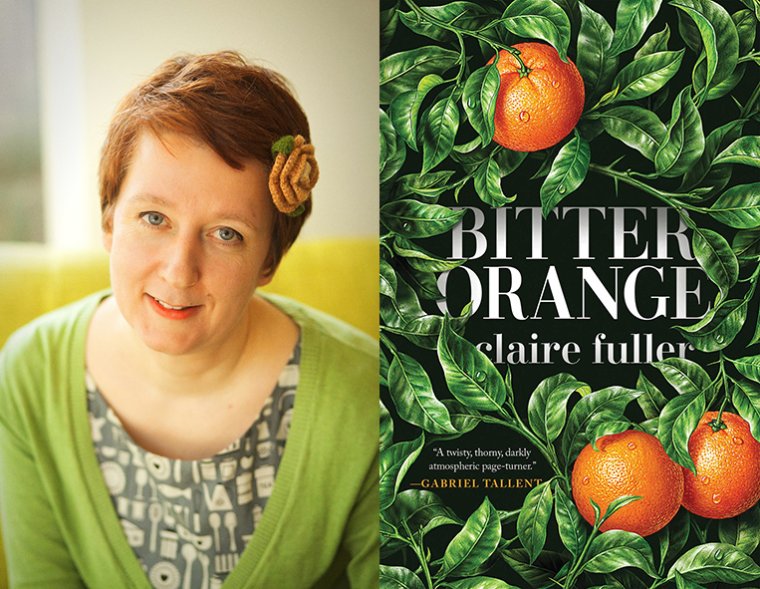

I have a predictably overambitious new year’s resolution to read a book of poetry, a novel, a book of short stories, and a book of nonfiction each month. Right now I’m reading People Like You by Margaret Malone, which is dark and funny and sublime; Claire Fuller’s Bitter Orange, which feels marvelously escapist and lush and has been keeping me up too late; Sister Outsider by Audre Lorde, who needs no adjectives; and I’m anxiously awaiting Paige Ackerson-Kiely’s new book, Dolefully, a Rampart Stands.

6. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

Discovering and falling in love with an author is such a private activity. When you meet someone who loves the same writer you do, it becomes a kind of shorthand for a shared aesthetic or philosophical worldview. I nearly knocked over my wine glass with excitement when I met a woman who wanted to talk about Canadian author Elizabeth Smart as much as I did. That’s not wide recognition, but it’s a form of literary community, and that’s probably more lasting in the end.

7. Would you recommend writers pursue an MFA?

Getting my MFA was the best decision of my adult life, and I loved my program at Sarah Lawrence. I wanted to be able to teach at the college level, I knew what I wanted to work on, and I had some money saved to pay for part of it. But I think it depends what a writer is looking for in their creative life (structure, guidance, encouragement, time), the package offered by the school, and their long-term career goals. If you have the resources to devote two or three years to the world of language and ideas, I found it a powerful and blissful experience.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

The mental space daily life demands. Buying a birthday present, calling the insurance company, grocery shopping, dishes, e-mail. This was captured so well in the comic The Mental Load, which focuses on parenthood but applies equally to keeping the lights on and the toilet paper replenished, if you ask me. This is why I love residencies. I honestly cannot believe how much more space I have in my brain when I am not thinking about how and what to feed myself three times a day.

9. What trait do you most value in agent?

I trust my agent, Grainne Fox, to always tell me the hard thing. That she does so with a soft touch and incomparable charm is proof she’s for me. I trust her implicitly, and we get on like a house on fire. That’s the foundation for any great relationship.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

You must find pleasure in the work itself—doing the work. Otherwise, what’s the point?

Sarah McColl, author of Joy Enough. (Credit: Joanna Eldredge Morrissey)

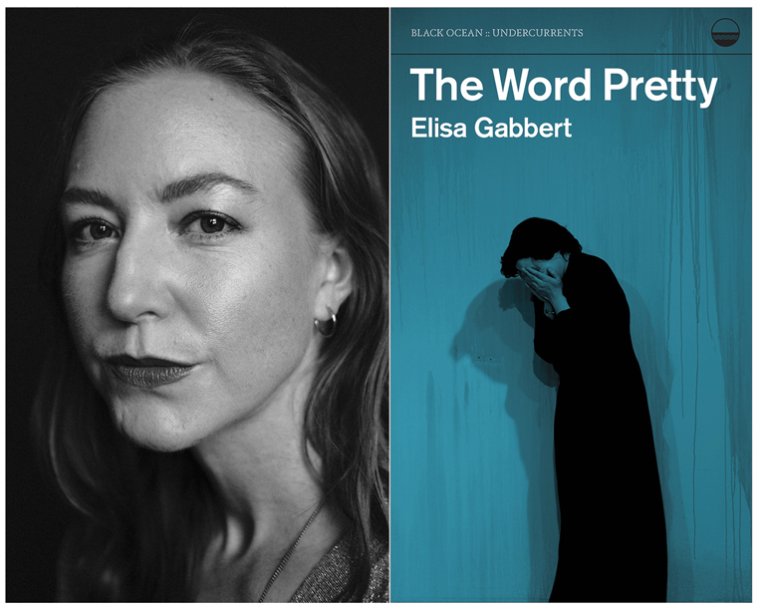

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Elisa Gabbert, whose essay collection The Word Pretty is just out from Black Ocean. Part of the press’s new Undercurrents series of literary nonfiction, the book combines personal essay, criticism, meditation, and craft to offer lyric and often humorous observations on a wide range of topics related to writing, reading, and life—from emojis and aphorisms to front matter, tangents, and Twitter. Gabbert is the author of the poetry collections The French Exit and L’Heure Bleue, or the Judy Poems; and a previous collection of essays, The Self Unstable. Her poems and essays have appeared in the New Yorker, the New York Times, A Public Space, the Paris Review, Guernica, and the Threepenny Review, among other publications, and she writes an advice column for writers, The Blunt Instrument, at Electric Literature. She lives in Denver.

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I just turned in a manuscript, another collection of essays, and the way I wrote that was very specific: For between one and three months, depending on my time constraints, I’d surround myself with, or submerse myself in, material on a topic—for example nuclear disasters, or “hysteria,” or memory—and read and watch films and think and take tons of notes. Then after a while the essay would start to take shape in my mind. I’d outline a structure, and then block off time to write it. As this process got systematized, I became more efficient; for the last essay I finished, I wrote most of it, about 5,000 words, in a single day. It was pretty much my ideal writing day: I got up relatively early on a Saturday morning and wrote until dark. Then I poured a drink and read over what I’d written. Of course I wouldn’t be able to do that if I didn’t give myself plenty of processing time. I can write 5,000 good words in a day, but I can only do that maybe once a month. I did most of the work for this book, the note-taking and the actual writing, sitting at the end of our dining room table. I try not to write at the same desk where I do my day job.

2. You write both poetry and prose; does your process differ for each form?

Yes. With prose, all I need is time to think and I can generate it pretty easily; a lot of my thoughts are already in prose. Poetry is harder. I feel like I have less material, and I can’t waste it, so it’s this delicate, concentrated operation not to screw it up. It feels like there’s some required resource I deplete. And I have to change my process entirely every three or four years if I’m going to write poems at all. Basically I come up with a form and then find a way to “translate” my thoughts into the form. It wasn’t always like that, but that’s the way it is now. I used to think in lines.

3. How long did it take you to write The Word Pretty?

I hadn’t set out to write a book, per se; I was just writing little essays until eventually they started to feel like a collection. But I think I wrote all of them between 2015 and 2017.

4. What has been the most surprising thing about the publication process?

I hope this doesn’t sound like faux humility, but I am surprised by the number of people who have bought it and read it already. I thought this was one for, like, eight to ten of my super-fans. We didn’t have a lot of time or money (read: any money) to promote it. What doesn’t surprise me is everyone commenting on how pretty it is. Black Ocean makes beautiful books.

5. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

One thing? I’d like to change a lot, but I wish both were less beholden to trends and the winner-take-all tendencies of hype and attention.

6. What are you reading right now?

I just finished reading Claudia Rankine’s Don’t Let Me Be Lonely cover to cover—I’d only read parts of it before—which got me thinking about the indirect, out-of-sequence nature of influence. My second book, The Self Unstable, looks the way it does (i.e. little chunks of essayistic, aphoristic, sometimes personal prose) in part because I’d just read a few collections of prose poetry I really liked. One was a chapbook by my friend Sam Starkweather, who was always talking about Don’t Let Me Be Lonely. This was years ago, before Claudia Rankine was a household name. I finally read the whole book and thought, “Oh! This was an influence on me!” Next I am planning to reread The Bell Jar, which I last read in high school, in preparation to write about the new Sylvia Plath story that is being published in January. I have an early copy of the story as a PDF, but I haven’t even opened the file yet. I’m terrified of it.

7. Which author, in your opinion, deserves wider recognition?

I didn’t invent Elizabeth Bowen but I just read her for the first time this year and she blew my mind. I’m always telling people to read this hilarious novella about Po Biz called Lucinella by Lore Segal, and Journey by Moonlight by Antal Szerb, one of the best novels I’ve ever read. Michael Joseph Walsh is a Korean American poet I love who doesn’t have a book yet. Also, some people will find this gauche, but my husband, John Cotter, writes beautiful essays that don’t get enough attention.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Not being independently wealthy, I guess? I have a job, so I can only work on writing stuff at night and on the weekends.

9. What’s one thing you hope to accomplish that you haven’t yet?

It would be nice to win some kind of major award—but that would really go against my brand, which is “I don’t win awards.”

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?

The best writing advice is always “read stuff,” but you’ve heard that before, so here’s something more novel: My thesis advisor, a wonderful man named John Skoyles, once said in a workshop—I think he was repeating something he’d heard from another poet—that if a poem has the word “chocolate” in it, it should also have the word “disconsolate.” I took this advice literally at least once, but it also works as a metaphor: that is to say, a piece of writing should have internal resonances (which could occur at the level of the word or the phrase or the idea or even the implication) that work semantically like slant rhymes, parts that call back softly to other parts, that make a chime in your mind.

Elisa Gabbert, author of The Word Pretty. (Credit: Adalena Kavanagh)

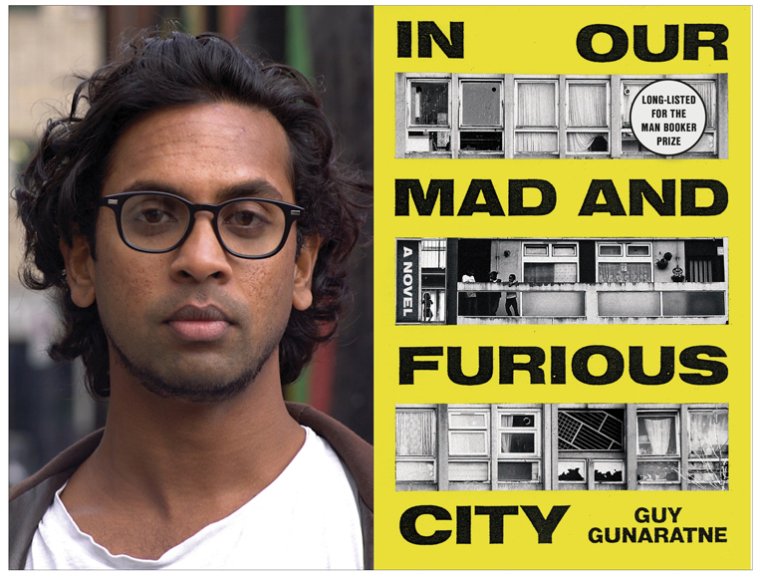

This week’s installment of Ten Questions features Guy Gunaratne, whose debut novel, In Our Mad and Furious City, is out today from MCD x FSG Originals. Inspired by the real-life murder of a British soldier at the hands of religious fanatics, Gunaratne’s novel explores class, racism, immigration, and the chaotic fringes of modern-day London. Longlisted for the 2018 Man Booker Prize and shortlisted for the Goldsmiths Prize and Gordon Burn Prize, In Our Mad and Furious City tells a story, Marlon James says, “so of this moment that you don’t even realize you’ve waited your whole life for it.” Gunaratne was born in London and has worked as a journalist and a documentary filmmaker covering human rights stories around the world. He divides his time between London and Malmö, Sweden.

1. Where, when, and how often do you write?

I write in my study, in Malmö. A large wooden desk, surrounded by books set where I left them. I write as much as I can, when I can. The most focused period tends to be early mornings, between 5 AM and 6 AM to 9 AM, and then in dribs and drabs throughout the day.

2. How long did it take you to write In Our Mad and Furious City?

The novel took about four years to write the initial manuscript and then another year with my editor. As someone who enjoys the solitary commitment of writing, I didn’t quite know what to expect in terms of collaborating on it. I’ve found the process to be rewarding and instructive.

3. What trait do you most value in an editor?

Patience, probably. And space. Once when working on In Our Mad and Furious City, my editor and I were working on a specific part of one character’s voice. She asked me to go away and think about a few specific things. She gave a list. “Just think,” she said. She gave me the time to simmer, which I think is important when making any significant change.

4. What was the most surprising thing about the publication process?

I try, sometimes with difficulty, not to be cynical about the relationship between art and industry. My hopefulness comes from knowing that there are usually enough dedicated people in any industry who are committed to doing good work. My surprise comes from finding out that I’d actually underestimated the amount of good people I’d meet during the process.

5. What is one thing you’d change about the literary community and/or the publishing business?

I think about this more as a reader than as a writer. I think we can all agree that homogeneity in any industry is unbearably boring. I’m interested in reading anything surprising, challenging, and provocative, in the best sense of the word. But I do wonder, at least with my experience thus far, how anything truly new, different, or challenging can ever come out of an industry that looks and acts so conservatively. There is still vitality here, and a desire to experiment with what gets published. The challenge is in encouraging those voices to keep on.

6. What are you reading right now?

I’m currently reading a nonfiction book called Rojava by Thomas Schmidinger, which is about the Kurds of Northern Syria. And I’ve finally got around to Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream.

7. Who is the most underrated author, in your opinion?

More people should be reading Machado de Assis and Nawal El Saadawi. But I think, more generally, people should be reading translated fiction. One of the beautiful things about the novel is its capacity to offer the reader a way to transgress beyond the parochial or familiar. It opens new territory to explore. At times it can even help confront learned biases that you wouldn’t have known were there. Many of my most surprising and enriching experiences have come from reading translated fiction.

8. What is the biggest impediment to your writing life?

Inevitably, there was always going to be a degree of friction because of the time I now commit to the public side of all this—the events, publicity, the travel. I think I underestimated how much all that would impact the other side, the writing side. Not to say I don’t like the public facing part. Engaging with readers, for example, I think is hugely rewarding. I find it a privilege, honestly. But I do find myself missing home quite a bit. I find that I need to have an extended period writing in once place in order to gather momentum. Sadly, I’ve been flitting back and forth, which doesn’t help.

9. What’s one thing you hope to accomplish that you haven’t yet?

I don’t have any external goals with my writing, not really. Right now I just want to write, publish, and keep writing. If I’m still writing novels in my sixties, it would mean that I would have attained something I had once thought impossible. Namely, a writer’s life.

10. What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever heard?