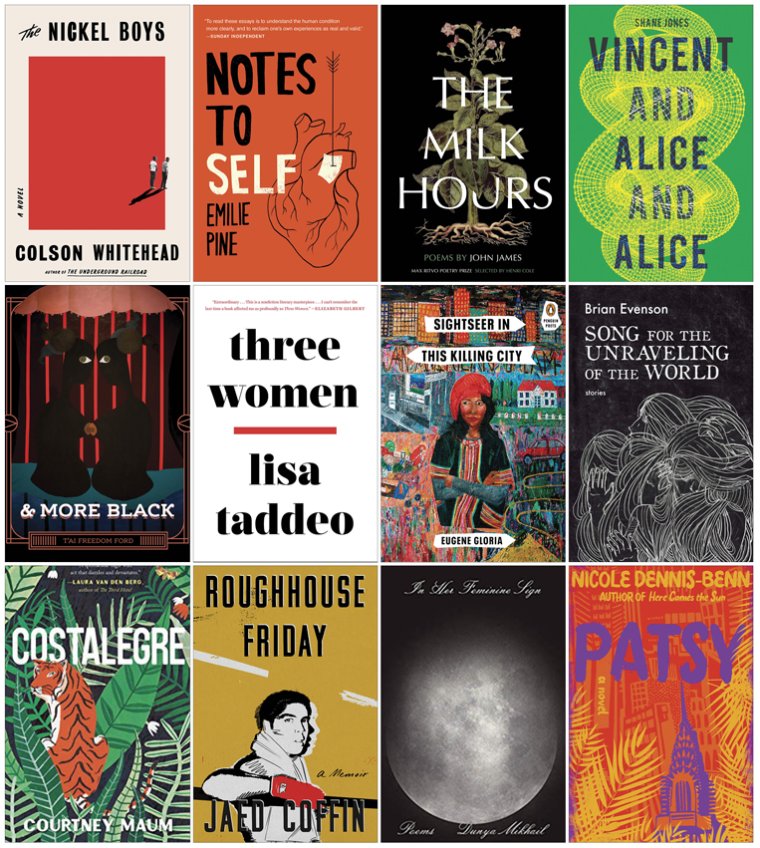

First Fiction 2019

For our nineteenth annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five established authors to introduce this year’s group of debut writers. Read the July/August 2019 issue of the magazine for interviews between Ruchika Tomar and R.O. Kwon, Chia-Chia Lin and Yaa Gyasi, Miciah Bay Gault and Melissa Febos, De’Shawn Charles Winslow and Helen Phillips, and Regina Porter and Jamel Brinkley. But first, check out these exclusive readings and excerpts from their debut novels.

A Prayer for Travelers (Riverhead, July) by Ruchika Tomar

The Unpassing (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, May) by Chia-Chia Lin

Goodnight Stranger (Park Row Books, July) by Miciah Bay Gault

In West Mills (Bloomsbury, June) by De’Shawn Charles Winslow

The Travelers (Hogarth, June) by Regina Porter

A Prayer for Travelers

Ruchika Tomar

There were three names listed under Cruz in the phone book, but I didn’t bother trying any of them. Ask Flaca. If Lourdes had been hostile to my call, Flaca, I knew, would hang up the minute she heard my name. I had always considered Penny their favorite; she was always the most admired in school, the one other girls strove to emulate. But Flaca was their backbone, the mainstay, the friend who dispensed favors and counsel. I decided to look for her in the one place I knew she would eventually be forced to return.

It was already dark when I left the diner, but I could have found my way to the palo blindfolded, even with all light stripped away. The Cruzes’ panadería was a flamingo pink storefront at the southernmost corner of a petite arc of businesses that included, among other things, a smoke shop and a laundromat. I parked the truck and climbed out as the barber was closing up for the night, unplugging the red and blue helix in the window, locking the door, rolling a hatched metal gate over the glass. He locked it, rattling the grille to make sure it was secured. Only the bakery stayed open late enough for workers returning from Sparks and Tehacama to drop off their lunch pails and tool kits at home, hunt their children from varied backyards, and corral them to the bakery for tortas and Cokes. As I walked to the entrance, a large blue van pulled up to the curb, unloading a dozen women in identical pressed white uniforms. These women were Pomoc’s illusionists, soon to be ferried out to office buildings and casinos and hospitals in southern cities, armed only with plastic bottles and brooms to toil unseen, tasked with erasing our collective past. I followed them inside and lingered near the wall opposite a glass case full of pan dulces tucked into neat, full rows. The women placed orders for tacos de piña, puerquitos, and coffee strong enough to power them through the evening into the pardoning dawn. Behind a small screen that separated her from customers, Maria’s short, corpulent figure bent to the glass case, shaking out one paper bag after another.

When I was a child, Lamb had brought me here so often that Maria often emerged from behind her veil‑like screen. She clasped me against her supple bulk, flattening dexterous, flour‑dusted fingers across my eyebrows and down the dark tails of my schoolgirl plaits, humoring Lamb with his awkward gringo patois while checking for my growth spurt that never seemed to arrive. Even after all these years her face was still full, a few strands of silver in her high, tight bun catching in the light. When the last of the uniformed women left, I unlatched myself from the wall and stepped up to the counter, searching Maria’s expression for some sense of recognition, an acknowledgment of the pigtailed tomboy who loved her. She nodded at me through the screen. “¿Qué quieres?”

“Is Christina here?”

“No.” Her reply was sharp, as if this was a question she’d been asked too often. Flaca’s business was growing, and it wasn’t hard to guess how many others might have shown up in recent months, seeking a dispensary.

“I just want to talk to her.”

“¿Quieres comprar algo?”

“I used to come here.” I held out my hand flat at my chest, indicating a child’s height. “This tall, overalls. I came with my grandfather. We sat over there.” I pointed to the corner table, the hard plastic chairs. She shrugged.

“You don’t remember me?” My voice sounded more desperate than I intended. What if I split my hair in braids again, if Lamb were beside me, if I clung to his rough hand the way I had then? Instead I pointed to a row of pink conchas behind the glass, as if nostalgia might stir Lamb’s dwindling appetite. “Cuatro, por favor.”

She reached for a pastry box and laid the conchas down like sleeping children. I paid and on my way out, held the door for a father shepherding inside twin girls, the pair of them in light‑up princess sneakers and vague, kittenish smiles. Outside, I stopped at the truck and slid the pastry box on the hood to fish the keys out of my pocket when out of the corner of my eye, I saw a mouse dart out from underneath a nearby car, scurrying along the side of the building to the dumpsters crowding the small back alley. Lamb and I had wandered there more than once to discard our trash, and I knew at the end of the alley lay the bakery’s kitchen where, during any weekday lull, Maria could be found chatting with any number of family members who cycled through to mix dough and answer the phone, transcribing elaborate cake orders. I settled the pastry box in the passenger seat of the truck before shutting the door and picking my way into the dark passage, edging past the dumpsters. Halfway down I could make out a square of light on the brick wall opposite, the top half of the kitchen’s Dutch door pushed open, giving off a backdraft of heat. I peeked in past the tall, silver rolling racks of pastries pulled away from the wall, the working counters covered with bags of yeast, mixing bowls, rows of sweet breads cooling on wire racks. A fan in the corner of the room rattled as it worked, its face pushed up toward the ceiling to keep from blowing flour into powdered mist. A slim girl, her back turned to me, pulled open the top door of an oven, sliding a baking tray inside. She shut it and moved to lean over the fan, shaking out the bottom of the tank top that clung to her, a red bandanna tying back her hair.

“Flaca,” I called her name softly. She made no movement to signal she heard, but a moment later, a familiar pair of hard, dark eyes pinned mine. She crossed the room and reached for the Dutch door, her face already forming a scowl. I took a step back, one foot into the dirt. A voice called out something indecipherable from the other room.

“Nadie, Mama,” Flaca called back. She jutted her chin at me. “What do you want?”

“I need to talk to you.”

“Me? About what?”

“What else? Penny.”

Flaca studied me with an expression I didn’t know how to read. She pushed the door open wider for me to catch, but once inside reached for me so quickly I didn’t have time to pull away. She caught my jaw in her firm grip, moving my face back and forth carefully in the light as if it were a ruby or disaster, something to be appraised. Her breath tickled my chin. This, the closest we had ever been to each other, even as girls.

“Penny didn’t do this,” she said flatly.

“God. Of course not.”

Flaca released me, moving away. It was twenty degrees hotter inside the kitchen, and the skin on my arms began to take on a thin sheen. The room smelled overwhelmingly sweet, the pastries baking in the double oven. I followed her back to the counter where she picked up a silver sifter, shaking powdered sugar over a rack of wedding cookies.

“Dime. You pissed someone off.” “That’s not what I came to talk about.”

“Oh? What does Cale want to talk about?” She set down the sifter and lifted the tray, sliding it onto one of the rolling racks.

“Penny never showed up to work last night,” I spoke to her back. “Maybe you’d know where she is.”

“I have no idea.”

“But you’re always together.”

“So are you,” she said, turning to shoot me a look. “Lately.”

“Flaca, I went to her place. She didn’t answer. I used the spare. She wasn’t there but she left her cellphone behind. You don’t think that’s weird?”

“That Penny forgot her phone?”

“She didn’t forget it. And she hasn’t come back, not that I know of.”

“Where is it now?”

“What?”

“Her phone, Cale.”

I hesitated. All the drops Penny was making for her, the business Flaca would lose if Penny didn’t have it on her. There was no good way to deliver the news.

“I might have given it to the police.”

“What!”

“I’m sorry! That’s why I’m here.”

Flaca rubbed her face, smearing flour down her cheeks. The bandanna pulling back her hair brought her features into stark focus; the angle of her cheeks and chin, her nose a degree too sharp. I longed for Flaca’s mother to emerge from the front of the shop, to see mother and daughter standing side by side and compare their faces and hands, to ask how some things could be passed down so easily from one to another while other familial aspects were entirely betrayed.

“I didn’t know what else to do. Maybe it could help? I have a feeling—”

“A feeling!”

“Something could be wrong.”

“And what are the cops going to do?”

“Help find her?”

Flaca laughed. In all the time we had been in school together, I couldn’t recall the sound. I had never heard it, or I had heard it too often; it had dissolved into the childhood soundtrack of playground sounds along with the recess bell, the squeak of swing sets, the rhythmic whip of jump ropes slapping the blacktop. It cracked her face wide open, making her appear less birdlike, revealing a pliable warmth: a secret she had kept hidden inside herself all this time.

“You can’t help it, can you?”

“They’re probably going to call you,” I said.

“The cops aren’t going to do shit.”

“How do you know?”

“I know.”

I met her eyes. “If they don’t, who will?”

“Relax. Penny’s fine. If she went somewhere, she’s already back and pissed you went through her shit.”

“Where could she go? She doesn’t have a car.”

“She can get a ride.”

“You’re the one who gives her rides!”

“I’m not the only one.” She said it pointedly, something in it I was supposed to extract.

“Fine. Okay? Say she got a ride. Why hasn’t she come back yet?”

She looked heavenward, as if the answer was soon to arrive. “You don’t understand. She thinks she’s like you. But we’re not anything like you.”

“What’s so wrong with me, anyway?”

“For one thing, you’re dumb about things you never had to know about.”

I realized we were standing at a cross angle from one another, that I had one hand on my hip, that she had both on hers. I wanted to drop my hand, to tell her where I’d found Penny’s phone, and how, the rolls of cash in the freezer, what they might mean. If Penny was here, she would have trusted Flaca enough to tell her about the desert and the sand‑colored man, everything. If we were going to traffic in secrets, Flaca’s could rival us all. Flaca was surveying the pastries on the counters, a curious expression growing on her face, as if they were bizarre, diminutive creatures struggling toward life.

“What is it?”

“How long has it been?” Flaca asked.

“Since she’s been gone? I don’t know. She was supposed to be on shift the night before last. What time is it now?”

“Almost eight. So what is that? Two days? Three?”

I didn’t answer. She looked up, finally seeing me. The wheels in her mind, I could tell, were beginning to turn.

“You have an idea. Someplace she could be.”

“No,” she said. “But maybe I can find out.”

Excerpted from A Prayer for Travelers by Ruchika Tomar. Published by Riverhead. Copyright © 2019 by Ruchika Tomar.

(Photo: Dan Doperalski)The Unpassing

Chia-Chia Lin

Pei-Pei was the only one home when I woke.

“How are you feeling?” she asked. It was a real question, without sarcasm.

The door was open, but no sounds drifted in from the other parts of the house. From my bed I could see Pei-Pei lying on her stomach, kicking her legs. My pillow obstructed part of my view. Her bare feet swung in and out of my sight.

“What time is it?” I asked.

“One or two.”

She was still in her sleeping clothes, a set of faded blue long johns with sleeves that were too short. The elastic at the wrists was loose. Her long black hair was tied back, and the shorter front pieces were matted to her temples. When I swung my legs out from the covers, I was wearing pants I had never seen before.

“It’s Tuesday,” she added. “You went to the hospital.”

“You’re not in school?”

She didn’t respond. Her legs pedaled the gummy air.

“We have to go,” I said. “They’re showing the launch. Did we miss it already?”

She nodded. “Yeah, it was last week.”

“Last week?”

“It exploded.”

“What?”

“Everyone died.” She sat up and stared at me, evaluating something in my face.

“What are you talking about?”

“There was a huge cloud of smoke, and then nothing came out of it—no shuttle.”

“What?” I looked around to see if someone, my father or Natty, was laughing at me from the closet. But the door was open, and there were no legs or feet beneath the hanging clothes.

“Believe me. I saw it happen.”

I shook my head, trying to find room for what she was saying.

“There’s something else,” she said. She pushed at a spot on the bridge of her nose. Her face was completely bare and her hair was clawed back. Behind her thick glasses her lashes were sparse, and her eyes were very small and black.

Suddenly I was afraid to look at her face. I tried to smooth the folds in the fitted sheet. It was not my usual one, and the fabric was all twisted and bunched. Later I would discover it was too big for my bed. When I helped my mother change it, we had to shove handfuls of it under the mattress, hiding its excess.

“Ruby’s dead.”

I laughed. I pressed on a wrinkle in the sheet with the heel of my palm, trying to spread it flat.

Pei-Pei took off her glasses and shook them as though they were filled with dust. “You heard me,” she said, “and I don’t want to say it again.”

“Stop joking,” I said.

“I’m not joking,” she said. “It happened two days ago.”

“How?” I asked. As I said it, I pressed a hand to my throat to stop a noise. There was an expanse between what I was saying and what I understood myself to be saying, and the giggle in my chest was trying to morph into something else.

“She got sick. There was an outbreak at school.”

“But she doesn’t even go to school yet.”

“No,” Pei-Pei said. “She doesn’t.”

We stared at each other. Without her glasses on, Pei-Pei’s eyes had expanded. They were not quite black, but the color of winter soil after the snow was scraped away.

Pei-Pei came to my bed. “It’s no one’s fault.”

“Get away,” I said.

She slipped her glasses back on and stood up. She walked to Ruby’s bed, leaned over it, and pulled the blinds up. Light washed over the room; the carpet turned from tan to blond, and the walls glowed. “We’re having a warm spell,” she said. The faded floral blooms on Ruby’s sheets were almost translucent as they bore the brunt of all that sun.

I gazed at Ruby’s bed. It was neat; she almost never slept in it. Her pillow was missing, though, and that one small absence made me uneasy.

After Pei-Pei left, I made my way to the window. I sat there trying to adjust my eyes to the light. Outside, at the end of our dirt driveway, were four trash bags, each opaque black and straining with contents I couldn’t fathom. The bags were knotted, dimpling on top, leaning on one another. One had fallen on its side. Soon I would find myself searching for things around the house: my backpack, my coat, my shoes. My mug, which I had chipped against Natty’s mug in a test to see whose was stronger. It began to seem that everything I had ever touched was missing. Or at least the things most familiar to me were gone.

Excerpted from The Unpassing by Chia-Chia Lin. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux May 7th 2019. Copyright © 2019 by Chia-Chia Lin. All rights reserved.

(Photo: F. Yang)Goodnight Stranger

Miciah Bay Gault

In the dimly lit kitchen—only a single bulb over the sink—I watched my brother’s eyes, huge, glassy. “It’s Baby B,” he said.

The stranger held still as if afraid to break a spell. His eyes moved from me to Lucas.

“Baby B is dead,” I said.

“I’ve been dreaming about him every night,” Lucas said. “I could sense him getting closer, and I thought there was something I was supposed to do. But it wasn’t me after all. You were the one who had to bring him here.”

“He’s a stranger, Lu. I met him tonight at the inn.”

“Then how do you explain this?” Lucas pointed at Cole’s ankle—at a small tattoo I hadn’t noticed. “Lady’s Slipper.”

We both looked at Cole. “I got that when I was twenty-one,” he said.

“Why that particular flower?” I asked.

“Why? Because it’s beautiful, and rare. And it was someone’s favorite flower—someone I loved—sorry, what is going on? Who’s Baby B?” A flush had risen from his neck to his cheeks. His eyes black, bright.

“He was our brother,” I said. “Sorry, maybe it’s time for you to go.”

“No,” Lucas said. “Don’t go! Here, sit down. I’ll get a beer for you, and we’ll tell you about Baby B. We’ll tell you the whole story.”

It was disorienting to see Lucas talking with a stranger, Lucas who sometimes couldn’t even say hi to Eddie, or the Grendles, or Jim Cardoza, people he’d known his whole life. I felt dizzy, as if the room were tilting around me.

“I’m always up for a story,” Cole said, sitting at the table. Lucas popped the tab on a PBR, and set it in front of Cole.

“I need to sit, too,” I said, and they pulled out a chair for me.

We were up until dawn, and I’m not exaggerating when I say that Lucas talked most of that time. It was as if something had come uncorked, and stories were pouring out of him.

“His name was Colin,” Lucas said. “I mean even your name is similar.”

“That’s just a coincidence,” I said.

“Did you feel anything?” Lucas asked me. “When you first saw each other, I mean? Did you have any idea?”

“I did,” the stranger said. “I felt something right away.”

“Of course I didn’t feel anything,” I said. “Because there’s nothing to feel.”

“Don’t worry,” Lucas said. “She’s always like this at first.”

“Like what?” I said. But I knew what he meant. Practical—trying to tether him to earth. He resented that. But look what happened when I slipped up, when I forgot myself for one night, tried to bring a stranger home, as if I were someone else, someone without responsibilities. Look how that worked out. I felt my heart beating, felt warmth crawling up the back of my neck, sweat prickling my scalp.

Just before sunrise, Cole went away down the chilly beach promising to come back the next day. Lucas and I stood on the screened-in porch, watched him disappear down the shore. Just before the second jetty, he stopped and found a stone in the sand, skipped it even though it was too dark to see its skittering path through the water.

“Did you see that?” Lucas said.

“It doesn’t mean anything. A lot of people skip stones.”

“In that exact place?”

As long as I could remember, Lucas had stopped at the second jetty to skip one stone. For good luck. For Baby B. I never knew why he did it. But in my memory I could see him at all these different ages, five years old, ten years old, eighteen, twenty-five. That same flick of the wrist. Stone after stone.

Lucas tipped his head back and finished his beer. For some reason neither of us wanted to go to bed. We sat on the porch until the grainy light of dawn made visible the dock and the jetties and the boats in the bay. I looked at Lucas and felt a deep ache in my chest—love swelling to enormous proportions inside my ribs. I loved him so much. I wanted to give him everything he wanted. A brother returned from the dead. Our parents too. If I’d known how to do it, what to sacrifice, I would have without hesitation.

It was ironic that our parents had decided to have children so they wouldn’t be alone when they were old. It turned out they didn’t need to worry about growing old at all. Dad had a heart attack when we were in seventh grade. Mom died eight years later—breast cancer. Ever since: just Lucas and me. Alone on the island, alone in the big house they bought for us.

Early light crept into the porch where we sat, lighting up the table and chairs, the wicker sofa, chenille blanket, potted plants. Everything was in place, but everything felt different. Bhone Bay was out there doing what it always did, tide creeping out, revealing damp raw sand, black sea weed. The red houseboat was anchored where it always was. The light was the same light. The sound of the bay was the same sound.

But we felt different now, already revised in some indefinable way. How amazing the change one day can bring, one chance meeting. Or—maybe not so amazing after all. After all we’d spent a lifetime longing for something—or someone—we could never have. That longing had created a space in us, in our lives, and Cole, in ways I didn’t yet understand, seemed to fit into that space, fill it like a missing puzzle piece.

Excerpted from Goodnight Stranger by Miciah Bay Gault. Copyright © 2019 by Miciah Bay Gault. Use with permission from Park Row Books/HarperCollins.

(Photo: Daryl Burtnett)In West Mills

De’Shawn Charles Winslow

In October of ’41, Azalea Centre’s man told her that he was sick and tired of West Mills and of the love affair she was having with moonshine. Azalea—everyone called her Knot—reminded him that she was a grown woman.

“Stop tellin’ me how old you is,” Pratt said.

“Well, I thought maybe you forgot,” Knot retorted. She was sitting at her kitchen table, pulling bobby pins from her copper-red hair. She picked up her glass and finished what was left in it. She had barely set it back on the table when Pratt picked it up and threw it against the wall. He then packed all his clothes in the old suitcase he’d brought when he moved into her little house a few years back.

“I’m gettin’ outta here,” he affirmed.

“Need some help packin’?” Knot shot back, and she laughed. It wasn’t the first time Pratt had packed that ragged bag. He stared at her, frowning.

“Drink ya’self to death, if that’s what you want to do.”

“Go to hell, Pratt.”

“I’m leavin’ hell!” he yelled.

A few days later, Knot came home and found a folded note peeping out from under her door. First, she looked down at the signature. When she saw Pratt Shepherd at the bottom, she took a chilled glass from her icebox, poured a drink, and sat down to look over the message. She read most of it. It said that Pratt was at his sister’s house, just across the lane. Knot wasn’t surprised. Pratt’s sister and her two little girls were the only family he had in West Mills.

In the letter, Pratt reminded her that he still loved her, still wanted to marry her, and still wanted to start a family with her. He wrote that he would wait around for just one week. Then he was going back home to Tennessee. That’s where Knot stopped reading. She laughed out loud, tossed the paper onto the table, and set her glass down on it. Funny—it was usually the books she used to teach her pupils that got the wet glass.

Knot would be lying if she told anyone that Pratt wasn’t a good man. He didn’t mind hard work, he picked up after himself, he kept his body nice and clean, and he knew how to give her joy in bed. But the truth was Pratt wasn’t much fun to her otherwise. He didn’t have much to talk about. And he couldn’t hold his liquor to save his life. After two drinks Pratt was laid out, spilling over, or both. Knot liked men who could match her shot for shot, keep her mind busy when they weren’t drunk, and still do all the other things Pratt could do. Aside from all that, her father—she called him Pa—wouldn’t like Pratt. If she were ever going to be married, it would have to be a man her pa loved just as much as she did.

Pratt’s threat to leave West Mills could not have come with better timing, because Knot’s twenty-seventh birthday was a week around the corner. When the weekend came, she walked down the lane—two houses to the left of her house—to tell her good friend Otis Lee Loving all about her newfound freedom. And since Knot visited him most Saturday mornings, and knew he would be in the kitchen, she didn’t bother knocking.

“You need to go on over there and fix things up with Pratt,” Otis Lee said. “Otherwise, he gon’ be on the next thing headed west.” Otis Lee set a cup of black coffee on the table in front of Knot; his face was angry-looking and peach. He didn’t sit down. Just then, his wife, Pep, showed up at the table with a boiled egg and a biscuit, all inside the cracked, sand-colored bowl Knot wished they would throw away.

“Pratt can catch the next thing to hell,” Knot replied.

Pep pushed the bowl in front of Knot, next to the coffee.

She didn’t sit down, either. Knot looked up at them and wondered what the day’s lecture would be about.

“Eat,” Pep commanded. Even at seven o’clock in the morning, her round face looked full and healthy, as though she had slept on a pillow made of air. Not the rough, feather-stuffed pillows Knot used.

“I thought I left my mama in Ahoskie,” Knot scoffed. “Y’all got anything I can pour in this coffee? Something ’sides milk, I mean.”

“Why you so set on bein’ lonely, Knot?” Otis Lee asked.

Pep looked down at Otis Lee as though he had gone off script. And he looked up at Pep as if to say, I couldn’t help myself. The way he and Pep stood there, side by side, made them look more like a boy and his mother than a husband and his wife. Why the two of them behaved so much like old people, Knot never understood. They were only five years older than she was. For Knot, it was Otis Lee’s being happily married, being too short, and old-man ways that ruined the handsomeness she’d seen on him when they’d first met. And that handsomeness, as striking as it was, had never caused the feeling Knot got deep in her stomach when she met a man she wanted to touch, or be touched by, in the dim light of her oil lamp.

“Y’all know he tried to beat me, don’t ya?”

Otis Lee and Pep both sighed, at the same time. Knot wondered if they had rehearsed it.

“You sit to my table and tell that tale?” Otis Lee reproached. Then he began with his You know good’n well this and You know good’n well that. At times like these Knot had to work hard to keep her cool. Because if she didn’t, she might tell Otis Lee that if he spent more time worrying about his own life, and his own family, he might know that the woman he knew as his mother, wasn’t; she was kin but not his mother. If his real mama is anything like mine, better for him if he don’t know. Ain’t none of my business anyhow.

“Tell me one thing,” Knot said. “Why y’all always take his side?”

“It ain’t just about Pratt’s side, Knot,” Otis Lee insisted. “You need to be nicer to everybody ’round here.” Knot heard bits and pieces of what Otis Lee recounted about how her drinking had gotten out of hand; how she seemed to want to be by herself more than anything nowadays—unless she was at Miss Goldie’s Place, of course. Knot started nibbling on the biscuit and then on the egg, trying not to hear all the things she already knew about herself.

Otis Lee turned to Pep and mused, “You remember when she used to go see the children and they mamas, Pep? Used to visit people just ’cause she had time. People used to talk so nice about that, Knot. Thought the world of it. Didn’t they, Pep?”

“Yes, they did,” Pep replied.

Knot dropped the egg back in the bowl and asked, “Ain’t I sittin’ here, visitin’ with ya’ll right now?” Knot was certain they’d both heard her question, although neither of them responded.

“Now folk say you show up to that schoolhouse smellin’ like you bathe in corn liquor,” Otis Lee went on. “That’s ’bout all they sayin’ ’bout you now.”

“What people you talkin’ ’bout, anyhow, Otis Lee?” Knot said. She took a sip of the coffee. It was weak.

“What you mean, ‘what people’?”

“Y’all ain’t got but three or four hundred folk ’round here,” Knot pointed out. “And most of ’em is white folk who don’t know me from a can of bacon grease.”

“Some days you talk like you don’t live right here in this town,” Pep remarked. Knot couldn’t think of anything to say back.

She knew that some if not all of what Otis Lee was saying was true—about people whispering. Many times Knot had noticed how some of the women stopped talking when she came near them at the general store. And at the schoolhouse, she’d been a bit hurt by how some of the people had seemed as if they didn’t want to be seen speaking with her too long when they came to pick up their children. They’d ask how their little ones were doing with their lessons and then hurry off as though Knot had a sickness they didn’t want to catch.

Knot did her job. As much as she hated it, she did it well. No one had complained about her teaching. They couldn’t. So many of the ma’s and pa’s had themselves thanked Knot for the little rhymes and games she’d taught their children to help them divide a number quickly—without using paper and pencil. Or the funny ways she’d taught them odd facts. She remembered asking one of the boys one day, “Sammy Spence, what’s the capital of Iowa?” And once he’d answered correctly, she’d asked, “How you remember to keep the s’s silent?” and Sammy had responded, “My name got s’s, and they both make the s sound. But not for Des Moines, Miss Centre!” And Knot had said, “So you were listening, weren’t you?” And she had rubbed his head. When Knot had first arrived in West Mills, there were some eight-year-olds who couldn’t write their names. Her pa would have been just beside himself about that if she ever told him.

Otis Lee was still lecturing.

“You ain’t gettin’ no younger,” he cautioned. “Pratt love you to death, gal.”

“He left,” Knot said. “I ain’t throw him out.”

“This time,” Pep remarked, and she walked to the basin. “You got somethin’ to say, Penelope?” Knot shot back before realizing that her question would only bring on the second part of the Loving lecture.

Just three months earlier, Pep reminded Knot, she had thrown Pratt out for trying to do something nice.

“All he wanted you to do was stay home from that ol’ juke joint for one Friday night,” Pep recalled.

“But I felt like going,” Knot grumbled.

“He cooked a chicken for ya, child,” Pep said. “This one”—she pointed at Otis Lee—“can’t even boil eggs.”

“I can too boil eggs, Pep,” Otis Lee said. “You know good’n well I—”

“If I come home to a cooked hen,” Pep continued, “I’m gon’ sit with my man and eat.”

“He ask her to read to him, too,” Otis Lee informed his wife. “She tell him, ‘No.’ ”

Pep looked at Knot with shame.

Knot couldn’t deny any of it. It had been his request that she stay home and read to him that irritated her most.

“I read to folks all goddamn week long,” Knot had said to Pratt. “You crazy if you think I’m stayin’ home to read to yo’ big ass.”

“Selfish and stubborn,” he’d called her, shaking his head. And Knot had said, “I’m twenty-six years old. I can be selfish if I feel like it.” And Pratt had said, “Naw, you can’t, neither.” And Knot had yelled back, “Well, get the hell on out my house! Right now! And don’t you come back to my door.” He was back at her door, in her house, and in her bed in less than a day.

Otis Lee’s four-year-old son, Breezy, came scooting down the stairs on his butt. His little face was mashed flat on one side and his hair was full of white lint. He looked as though he’d been working in the cotton fields Miss Noni had told Knot all about. Breezy went and stood between his parents. Pep rubbed his head and pulled him against her thigh.

“Say good morning to Miss Knot,” Otis Lee nudged. And the boy did. Knot was glad Breezy was there to draw some of the attention away from her. She was done picking at the egg and biscuit, and done being picked on.

“You hear anything we just say to you, Knot?” Otis Lee asked.

Knot wiped her hands on the damp rag that was on the table.

“I thank y’all kindly for the breakfast. I’ll be goin’ on home now.”

“Go on over there and make things right with Pratt,” Otis Lee demanded. “You hear me?” He was looking at her as though she were a daughter or a sister he couldn’t control. Knot looked at Pep, and Pep turned and went to the icebox.

“The hell I am,” Knot said.

“Ma!” Breezy exclaimed. “Knot say a cussword!”

“I’m Miss Knot, lil boy,” Knot corrected. She couldn’t resist giving the boy a quick tickle on the neck. And she realized that she might be missing her nephews back in Ahoskie. “If yo’ ma and pa don’t let up, I’m gon’ let you hear some more cusswords.”

On her way out, she heard Breezy say, “Pop, Miss Knot got our bowl!”

Knot finished eating the egg and biscuit when she got back to her house, while she read a chapter of The Old Curiosity Shop. It was her pa’s favorite book, by his favorite author. And because he had read those big books to her with such joy, Dickens had become her favorite, too. Her pa had read that book to her more than twenty times when she was a small child. He used to sit on the floor next to her bed two or three times a week and read. Sometimes Knot saw specks of his patients’ teeth and blood on his shirts. It would make her mother angry.

“I ain’t got time to worry ’bout keepin’ shirts pretty, Dinah,” her pa would say to her mother. “Them folk be in pain when they come to see me. Half the time, they already tried to snatch the teeth out theyself.”

Knot’s pa shared with her his love for reading, no matter how tired he was. And each time, Knot would hold on to his long, rough goatee so that she would know when he got up. As hard as she would fight sleep, it won the battle every time.

On the night of her birthday, Knot spent close to an hour looking at the only five dresses she had liked enough to bring with her from Ahoskie. She modeled each of them for the little mirror on the wall. She had to stand far away from it to see her whole body. And when she walked close to it, most of what she saw was her pa’s V-shaped jaw. He couldn’t deny being my pa even if he wanted to. How many people in Ahoskie got a jawbone like Dr. G. W. Centre?

Knot ruled out the black dress and the white one. The pink one with the white bow, the green one with the blue trim, or the plain yellow one had to be the winner. Finally she chose the yellow one. She liked the way it looked next to her skin. Pratt used to tell her it made him think of peanut butter and bananas—something he loved to have on Sunday mornings. The dress was over ten years old, but that worked in Knot’s favor. It showed whatever curves she had, which Pep claimed were starting to go missing.

When the sun went down, Knot dressed up and bundled up. She walked the short distance—less than a quarter mile—to the dead end of Antioch Lane, to Miss Goldie’s barn house juke joint, where Knot knew people would be throwing away the money they should have been saving to buy their Christmas hams if they didn’t have a hog of their own. But with the Depression just behind them, and war hovering, ain’t nothing wrong with folk havin’ a drink or two in the company of other folk who want to have one or two.

Going alone to Miss Goldie’s Place reminded Knot of her first few weeks in West Mills, and on Antioch Lane, back in ’36. How nice it was to not have a nagging man looking over her shoulder, counting her drinks, or running off the friendly men she had met since moving there to take the teaching job her pa had arranged for her.

When Knot pulled open the big heavy oak door and stepped inside, the first thing she looked for was Pratt sitting at the piano, playing his tunes. He was nowhere in sight. What am I lookin’ to see if he here for? It’s my birthday. She would have stayed either way.

It wasn’t long before the friendly men started asking Knot unfriendly questions: You done put Pratt down again, Knot? And: Knot, is it true you plum’ put a piece of glass to Pratt’s neck? To some of the questions, Knot declared, “That’s a damn lie!” To other questions she replied, “That ain’t none of yo’ goddamn business.”

Knot left their tables and found company with the few men who didn’t know her name yet. And there was one, a young one, standing at the end of the counter. He was tall, just the way Knot liked them. He just might be the tallest man I ever stood close to. Pratt had held the record for the tallest and the stockiest. But this fellow was tall and slim.

Valley, Knot’s buddy who poured drinks at Miss Goldie’s Place, told Knot he was too busy to help her court. If she wanted to know who the young fellow was, she had better go and ask him herself, Valley said.

“And if he don’t seem interested in you, s—”

“Send him over to you?” Knot finished, knowing Valley’s taste in men.

“Yes, ma’am,” he whispered, and smiled.

“You ain’t gon’ be satisfied ’til you put yo’ mark on every man west of the canal,” Knot said. She and Valley laughed. Then he reminded her, first, that he hadn’t had any luck thus far and, second, that she’d promised to make him one of her famous Antioch Lane bread puddings before he was to leave to go out of town again. “Don’t start in with me about that damn puddin’, Val. If I do make it, I want my dollar—just like everybody else gives me for it.”

“I always pay you,” Valley said. “I don’t know what ya talkin’ ’bout.”

“You want me to go home and get my ledger?” Knot countered. Valley smiled and rolled his eyes.

Miss Goldie was sitting about midway along the bar, wearing overalls and a man’s shirt. She was smoking a pipe. Unlike most pipes Knot had seen the people of West Mills puffing on, Miss Goldie’s didn’t look as though it had been carved out of wood by a five-year-old. It was a nice pipe. Probably ordered it from Europe or somewhere.

Next to Miss Goldie was Milton Guppy, sitting there glaring at Knot as he always did. Knot never understood how he had gotten such a strange last name. The glares, however, weren’t a mystery to her. The teaching job her pa had set up for her had belonged to a Mrs. Guppy. And when Mrs. Guppy had been dismissed, she also dismissed herself from her marriage, taking her and her husband’s four-year-old son with her. No one knew where the two of them had gone, since she was rumored to have had no family to speak of. The mean looks Mr. Guppy gave Knot whenever she saw him—sometimes Knot thought he was even growling—were enough to let her know he hadn’t gotten over it. She sympathized. But it wasn’t my fault! I ain’t make her run off.

After a few months of Guppy’s glares, Knot had walked up to him once, up-bridge at the general store, and said, “If you got somethin’ to say, go ’head and say it and get it over with. I probably done heard it from other folk, anyway.” And Guppy had said, “I don’t b’lee I will, Miss Centre. Don’t want to make ya late for yo’ teachin’. Wouldn’t dare keep the good teacher ’way from the good teachin’ job she come here and steal.” And Knot had said, “I’m gon’ tell you the same thing I tell everybody else who got a problem with me being up at that schoolhouse.” And after she did, she’d told him, “Now you can go to hell.” She had left the general store without the hard candy she had planned to buy for the children.

Tonight, at Miss Goldie’s Place, Knot gave Guppy a Don’t look at me stare. She could tell by the evil look on his face that he must have already lost his week’s pay at the dice table.

Miss Goldie looked irritable, studying Knot and Valley. Finally, she cleared her throat in a loud This is for y’all to hear way. Knot knew Miss Goldie was watching every move in the building, and she didn’t like it when her workers carried on long conversation when they should have been refilling jars and glasses and collecting nickels and dimes.

Knot finished her first drink—it was her third, if she counted the two she’d had at home—and she danced over to that young man at the end of the bar.

“Tell me one thing,” Knot said to him. He was standing there in a suit. Lord, the man wore the whole suit to the juke joint. Whether it was navy blue or black, Knot couldn’t be sure. “You think yo’ people know you snuck out they house yet?”

“Well, if I had snuck out,” he replied, standing straight and putting his hands in his pockets, “they wouldn’t be able to find me. I’m a long way from home.” He didn’t sound anything like she would expect from a man of his height. He sounded as if nature had gotten tired and quit working halfway through his change of voice when he was a growing boy.

“I figured that part out already,” Knot said. And it wasn’t just the sharp suit that had given it away. His haircut can’t be more’n a day old. And he got the nerve to have a part shaved there on the side. Menfolk in West Mills don’t wear parts in they heads. Knot said, “I hear the North on ya’ tongue. Where’s home?”

“Wilmington,” he answered. “Wilmington, Delaware.

“I know where Wilmington is, thank you,” Knot retorted, and she wondered how she’d had all that schooling without learning there was more than one Wilmington—one other than in North Carolina.

She looked at him for as long as she could without feeling simpleminded. With teeth as straight and white as his, and with him not having a single razor bump on his chin, she was sure he wasn’t more than twenty years old.

“You can’t be more than nineteen, twenty,” Knot guessed aloud. He showed her a sly smile. I’ll be damned if he ain’t got dimples to go ’long with that grin. Shit, I don’t know if I ought to slap him or kiss him.

“People usually ask me what my name is by now,” he said.

Knot was about to tell him that she didn’t care what people usually wanted from him, but his eyebrows caught her attention. His eyebrows were so thick and neat against his smooth, black forehead, Knot wondered, If I stick the edge of a butter knife under the corner of one of ’em, would I be able to peel it off whole?

“Well, go ’head and tell me your name, then,” Knot said. He came closer to her, and she looked up at him.

“It’s William. And you guessed my age pretty close. I’m almost twen—”

“Buy me a drink, Delaware William. It’s my birthday.” Knot turned toward Valley and shouted, “Pour me what I like! This here fella’s gon’ give you the nickel.”

“William,” Delaware William corrected.

“Forgive me,” Knot said to him. And to Valley she said, “Delaware William’s gon’ give you the nickel.” When she looked back up at Delaware William, he was smiling again and shaking his head.

Valley came to the end of the bar where Knot was standing. With his finger, he signaled Knot to lean in. “Ain’t you got somewhere to be in the mornin’?”

“You ever hear tell of me not showing up?” Valley sucked his teeth. Knot said, “I didn’t think so. And I’ll thank you kindly to get me my drink. My damn birthday’ll be over, foolin’ with you.”

Valley fanned his bar rag at Knot. “You just as crazy as you can be, Knot Centre.”

“What was that he just called you?” Delaware William asked.

After Knot decided she wasn’t going answer him, she looked him up and down.

“My name’s Azalea.” And after he showed her a confused look, she said, “What’s ya business in West Mills, Delaware William?”

“I’m just William,” he said politely. “William Pe—” “What’s ya business here in West Mills, is what I asked,” Knot interrupted.

“We just stopped to rest. On our way back up from Georgia. Played some gigs down there for a few months.”

When she asked him to explain the we, he pointed to another young man who sat at a table with the pastor’s daughter. Knot was certain the girl had snuck out of the house. Without a doubt, it wouldn’t be long before the girl would give the young man what he wanted. Knot could tell by the way she was giggling. If the girl was anything like Knot was as a teenager, Knot knew how the night would end. And that young man would be leaving town soon after.

Knot, figuring she didn’t have more than a few hours with Delaware William, finished her drink in three swallows. Then she and Delaware William left, kissing and feeling on each other the whole walk back to her house. Between the heavy petting, she caught a few glimpses of the full moon. It was like an usher leading the way down an aisle.

“Looks like we’re in some damn slaves’ quarters or something,” Delaware William remarked. Knot couldn’t argue with him about that, even if she were sober. She had thought the same thing when she first moved to West Mills and rented the little house from a man named Pennington. According to Otis Lee and Miss Noni, Riley Pennington—Otis Lee’s boss—was a descendant of the line of Penningtons who had once owned the whole town, which, in those days, had been called Pennington, North Carolina. It didn’t change names until a man from Maine named Leland Edgars Sr. and his two sons—Miss Noni said they were both tall and handsome with long, pitch-black ponytails—moved to town with a bunch of Northern money. They bought up a bunch of land with trees and opened a mill on the west side of the canal, causing people to refer to the whole town as West Mills. And now, aside from the one large farm, the Penningtons owned only an acre here and an acre there.

“Used to be,” Knot said, and that was all she felt like telling him. “Now that you got ya history lesson, shut up and kiss me some more.”

When they arrived in front of her house, that same moonlight that had led them there showed her that Pratt Shepherd was sitting on her porch. He sat there as though he had been one of the first Penningtons.

“Young fella,” Pratt called out, “best if you turn around. Head on back up the lane so I can talk to Knot.”

Delaware William had his arm around Knot’s shoulder, and she felt it slide away. Knot leaned into him—she might have fallen over otherwise.

“Well, sir,” Delaware William said, “I didn’t hear her say she wants to talk to—”

“I used to know a boy that look something like you,” Pratt cut in. He stood to his feet. “Got his face cut up for walkin’ another man’s wife home. They cut that fella’s face up real bad. Right here on this lane.”

Knot didn’t get a chance to tell Delaware William that Pratt was no one to be afraid of; he had turned around and hightailed it back down the lane toward Miss Goldie’s Place. When Knot turned back around to face Pratt, he was sitting again.

“I’m gon’ count to ten . . . or eleven,” she slurred, steadying herself in front of the porch and placing her hands on her hips. “When I get through countin’, you best be off my damn porch or I’m gon’ have to hurt ya.”

“What? You got a gun, or somethin’?” Pratt taunted.

“Did you hear me say I got a gun?” Knot shot back. “I might, though.”

“Sit down, Knot. Sit on down here ’fore you fall and crack that lil head of your’n?” He patted the porch two times.

Knot spit on the ground and said, “My new man’ll come back and crack yo’ head open to the white meat.”

“Who?” Pratt asked. “The one that just run off? He ain’t even stay long enough for me to tighten my fist.”

Knot turned and looked down the lane. Delaware William may as well have been a ghost. Pratt, she discovered when she turned to him once more, looked as though he would die if he held his laugh in any longer. And once he let the laugh go—he slapped his knees, too—Knot said, “Go to hell, Pratt.”

She sat on the porch next to him and their shoulders touched.

“Happy Birthday, darlin’.” He leaned over and kissed her on the cheek. She swatted him away, but she was so glad he was there; something was stirring around inside her and she was in the mood for a man’s company.

Pratt pulled her close to him. She liked the way her ear felt against his fleshy chest. A whiff of his clean breath relaxed her. Pratt’s breath smelled as though he had chewed on mint leaves all day instead of just after dinner, as he usually did. Knot figured she would let him kiss her, knowing he’d happily join her inside the house, where he would make her feel good under the quilt. Hell, it’s my birthday.

In the doorway, Pratt kissed her face and neck. And before she knew it, they were on the bed they had been sharing, off and on, for two years. She didn’t know what it was, but it seemed as though his touch was different, better than before. “Feel like you grew some more hands,” she whispered in his ear before softly biting his earlobe. Did he put butter on his lips? She had never known his lips to feel as soft as they felt tonight. She enjoyed their new softness even more when Pratt kissed the insides of her thighs and moved up to her shiver spot.

Pratt laid his large body on top of hers. She imagined a giant pillow. As big—with just the right amount of heavy—as he was, that night he was a nice cloud hovering over her, making love to her. Knot knew she would certainly be hoarse in the morning.

Lord, have mercy.

When they were done, Knot lay there wishing Pratt would fall asleep so she could have one more drink. That jar is whistlin’ for me. But after all Pratt had just done for her, she didn’t want to spoil it.

The Dickens book was on the floor next to her headboard, so she decided to read for as long as her eyes would allow. But it sure would be nice to have a cool glass with a splash in it while I read. Damn! Pratt was wide-awake on the other side of the bed, picking with his toenails.

The next morning when Knot woke up, she lay there thinking about how she hadn’t gotten to do what she had wanted—in my own house. She nudged Pratt until he was awake.

“What is it?” he mumbled. He had one eye open, one eye shut.

“Get up!” Knot exclaimed.

“What for?”

“Get up and get the hell on outta my house.” And after he was dressed and about to walk out, she said, “And don’t darken my doorway. Never no mo’.”

“Azalea!”

“Gone!” she yelled, before slamming the door and making the drink she had wanted the night before.

Excerpted from In West Mills by De’Shawn Charles Winslow. Copyright © 2019 by De’Shawn Charles Winslow.

(Photo: Julie R. Keresztes)First Fiction 2018

For our eighteenth annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five established authors to introduce this year’s group of debut writers. Read the July/August 2018 issue of the magazine for interviews between R. O. Kwon and Celeste Ng, Fatima Farheen Mirza and Garth Greenwell, Jamel Brinkley and Danielle Evans, Katharine Dion and Adam Haslett, and Tommy Orange and Claire Vaye Watkins. But first, check out these exclusive readings and excerpts from their debut novels.

The Incendiaries (Riverhead, July) by R. O. Kwon

A Place for Us (SJP for Hogarth, June) by Fatima Farheen Mirza

A Lucky Man (Graywolf Press, May) by Jamel Brinkley

The Dependents (Little, Brown, June) by Katharine Dion

There There (Knopf, June) by Tommy Orange

The Incendiaries

by R. O. Kwon

It was past the time the march should have begun, and people were losing patience. I’ll give it five minutes, then I’m calling it quits, a man said. Placards leaned against a building wall. I saw John Leal talking to people I didn’t recognize. With a nod, he stepped on an upended crate. His mouth moved. In that hubbub, I couldn’t pick out his words. Phoebe apologized again, tearful. It’s all right, I said, but she had more she wanted to explain. It’s fine, I said. Hoping she’d calm down, I kissed Phoebe’s head. I was intent on listening to John Leal’s speech: I was curious what his effect would be with this large an audience, if they’d respond as we did. He lifted his head, pitching his voice.

. . . hands splashed with blood, he said. We’re all here this Saturday morning, and I know I don’t need to tell you the truth that an unborn child has a heartbeat before it’s a month old. I don’t have to tell you that, within the first three months of fetal life, a human infant’s strong enough to grip a hand. But I’m not sure if it’s done much good, all this truth. What point it’s had, if you and I aren’t saving lives.

Excepted from The Incendiaries by R.O. Kwon. Reprinted by permission of Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2018 by R. O. Kwon.

(Photo: Smeeta Mahanti)A Place for Us

by Fatima Farheen Mirza

Amar was the one they loved the most. He was the one whose picture Mumma kept in her wallet behind her license. Him smiling with a toothless grin. Mumma ran her fingers through his hair as if it nourished her. A painting he did of a boat on the ocean was tacked above Baba’s office desk when she visited him at work. Once Hadia spent an entire afternoon counting the faces in the framed pictures, and Amar had beaten them all by seven. Hadia and Huda were a two-for-one deal: if there was a framed picture of them, they were likely together. Mumma served food for Amar first, and then Baba, and she always asked Amar if he wanted seconds. She was not even aware of doing it. Hadia’s daily chore was washing the dishes and Huda’s was sweeping. If Amar was asked to help, the two of them would shout and cheer to mark the day. Sometimes this made Hadia so angry that if she was left in charge of the cleaning while Mumma and Baba were out, she would delegate everything to Amar. He was the only one Mumma had a nickname for. His favorite ice cream flavor was always stocked in the fridge; if Hadia helped unload the groceries and saw a pistachio and almond carton, she reminded Baba that Amar was the only one of them who ate that flavor.

“You don’t love it too?” Baba would ask her distractedly, every time.

“No,” she’d say quietly, thinking there was no point in correcting him at all.

Once, only once, had she confronted her mother about this, after her mother had taken his side during a fight that he was clearly to blame for.

“You love him more,” she had shouted. “You love him more than all of us.”

“Don’t be silly.” Her mother was calm, as if she was bored by Hadia’s tantrum. “You think about him more. What he needs and what he wants.” Hadia had turned to run back into her room. “We worry about him more,” her mother had called after her, so gently that Hadia had wanted to believe her. “We don’t have to worry about you.”

She had sniffled, and locked her bedroom door, embarrassed by her outburst. She plotted to do something that would make her parents worry about her, as if their worry would prove the depth of their love. But she was afraid. They had endless patience for Amar’s antics. She feared the only thing worse than wondering if they loved him more was testing their patience, proving it to be thin, and knowing for certain.

They loved Hadia because she did well. Her grades were good and her teachers said kind things about her. She was not sure if Baba would even notice her at all, if she did not work hard to distinguish herself academically. The only compliment Mumma ever gave her was that when Hadia cleaned the stove, it always sparkled.

“Even I can’t clean like that,” Mumma would say. And there would be actual awe in her voice, and Hadia would never know if she should feel glad for the compliment, or annoyed that it was the only thing that Mumma valued enough to note.

Amar was their son. Even the word son felt like something shiny and golden to her, like the actual sun that reigned over their days.

Baba would sometimes say to Hadia, “One day you’ll live with your husband. You’ll care for his parents. You’ll forget about us.”

It was meant as a joke, “you’ll forget about us,” or “we will no longer be responsible for you.” But it was never funny.

“Amar will take care of us, right, Ami?” Mumma would squeeze his cheeks. Amar would nod.

“Why can’t I?” she would say.

“Because the role of the daughter is to go off, to make her own home, to take her husband’s name—daughters are never really ours,” Baba would tell her.

But I want to be yours, she’d want to say. I want to be yours or just my own.

“I won’t take anyone’s name,” she’d vow aloud, but he would have stopped listening.

Everyone important was a boy. The Prophets and the Imams had been men. The moulana was always a man. Jonah got to be swallowed by the whale. Joseph was given the colorful coat and the powerful dreams. Noah knew the flood was coming. Whereas Noah’s wife was silly and drowned. Eve was the first to reach for the fruit. But Hadia liked to keep her examples close. It was Moses’s sister who had the clever idea to put him in the basket, and the Pharaoh’s wife who had the heart to pull him from the river. It was Bibi Mariam who was given the miracle of Jesus. Bibi Fatima was the only child the Prophet had and the Prophet never lamented the lack of a son. And she liked to think that there was a reason that one of the first things the Prophet ever did was forbid the people of Quraysh from burying their newborn daughters alive. But still, hundreds and hundreds of years had passed, and it was still the son they cherished, the son their pride depended on, the son who would carry their name into the next generation.

Excerpted from A Place for Us by Fatima Farheen Mirza. Copyright © 2018 by Fatima Farheen Mirza. All rights reserved. Published in the United States by SJP for Hogarth, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

(Photo: Gregg Richards)

A Lucky Man

by Jamel Brinkley

James kept busy at the security desk now, doing the work of both men while Lincoln sat there with his stomach on his lap. He felt a sort of bond with James now, a familiar gratitude. But one gets sick and tired of saying thank you. When he was engaged to Alexis, and during their first years of marriage, his friends would also tell him how lucky he was, but this was said as a joke. Lincoln would say thank you and agree, would tell them how grateful he was for her, but this wasn’t true. He deserved her—this was what he believed, and he knew this was what his friends believed in. A man of a kind should get what he deserves, and if a man like him couldn’t get a woman like her, then something was terribly wrong with the world.

James snipped withered leaves from the spider plants, a thing he’d never done before. Do her friends tell her she’s lucky? Lincoln wondered. Has Donna said that to her? Has her mother told her to give thanks for her man? She might be saying it now as they picked plums and nectarines at the fruit market, or sat out on the porch shelling peas. Surely this was foolish thinking, just as foolish as thinking Tameka would spend these years breaking the hearts of any eager Georgetown boy who wasn’t like her father. Lincoln came to understand that this had always been part of his vision for himself, to have children who adored him—a son who resembled and worshipped him, a daughter for whom no other man would ever measure up. This was part of what he couldn’t see before he married. But there was no son, and the years of Tameka’s life had marked his decline.

She had grown up watching it. His professional gambles with the boxing gyms, and the attempts at training and managing, had failed. His charm and stature no longer earned him opportunities, and in New York he had no reputation. He was lucky, he knew, to have his job at Tilden, steady and respectable work, but years ago he and his wife had deserved each other. Time had not treated them equally. Why did he expect otherwise though? With any two people one would get the brunt of it, and time had hit him worse than any beating he’d ever seen in the ring. He felt it had brutalized him. What did his wife think? Alexis had always been kind and supportive, but in her privacy she had to keep thoughts. A long marriage forced you to witness or suffer such brutality. Lincoln wondered, not for the first time, if this was exactly what marriage meant.

Across from the front desk, James pulled the director of security aside. Lincoln couldn’t hear what they were saying, but the discussion had the look of seriousness. He approached, but the director stopped him short with a flat stony hand, which he closed into a fist before lowering. Lincoln went back to his chair.

One day his wife’s looks would go. Creases would line her face, the skin there would loosen and thin, pouches would form under her eyes, maybe little dewlaps like his under the jaw. And her mind, it would start to slip and show weakness too. Everything cracks eventually. But when? How long would it be his good fortune to have her? How long until he could just plain have her again? Her smooth face. Even after all these years he longed for it, to rub his cheek against hers and breathe hot words into her hair—there’d been no diminishment of that feeling. He still had those appetites, and she did too. Yet he also felt the urge to press the sharps of his teeth against her face, to bite down and place the first deep crack in it. When pulled by contrary desires, you often don’t do anything at all. So on evenings and weekends he’d sit at home like a chastened boy, captive to her every small gesture. He didn’t want to lose her.

But Lincoln was a man with luck—yes, he still had it, James had said so and he was right. Good fortune can change in an instant, however, or it might never, but whatever it does has nothing to do with you. For years it had persisted in following him. It went home from work with him, lived with his family, claimed a space between him and his wife in their bed. She still had her light, but his was his luck. If it left him, she would too. No one would blame her. Neither Donna nor her other girlfriends, nor her mother, nor their daughter. Nor James. Maybe James had been wrong earlier. Maybe Lincoln’s luck had already abandoned him—his wife was gone for now, after all. Or maybe Lincoln was the one with wrong notions—maybe, slumped in his chair at the desk, unable to muster the little strength it took to hold in his belly, it was his luck that he was alone with.

Excerpted from A Lucky Man by Jamel Brinkley. Copyright © 2018 by Jamel Brinkley. Reprinted by permission of Graywolf Press. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

(Photo: Arash Saedinia)

The Dependents

by Katharine Dion

His early forays on the internet had been limited to responding to the emails his daughter sent him and occasionally reading the sensationalistic but nevertheless impossible-to-ignore news stories that appeared on his home page. (He wondered if this was something Dary could tell from the settings—that he clicked on articles such as “Nude Man Accidentally Tasers Self” or “Beano Bandit Apprehended.”) When Dary realized how little he was using the computer she tried to help him, but the only thing that really stuck with him from her tutorials was this idea that you could ask the internet a question, any question, and it would give you not just one answer but dozens. He found this oddly reassuring because it suggested that somewhere on the other side of the internet connection, back in the human realm, somebody—and possibly a lot of somebodies—had the same semiprivate question that was more comfortable to send through a filtering layer of inhuman data.

Now he typed into the oracle field: “How to write a eulogy.” It was nice, or at least nonjudgmental, he supposed, that the internet assumed nothing about your existing abilities. Maybe you were a human willing to exert some effort, or maybe you were a half-automaton who needed to pass himself off as acceptably human. If he hadn’t wanted to write the eulogy there were plentiful options: premade templates, preselected themes, inspirational quotations, mournful yet triumphant poems. He was looking for something else, something that wouldn’t give him the shape of the thought, but that would tell him how to begin a process of thinking about the unthinkable.

He opened the top drawer of Maida’s dresser. She had never bothered to match up her socks, mixing them loose among her underwear and bras, and her pantyhose often ended up stretched beyond use or tangled in a knot. How many times had she and Gene been late for some event because on the way she had made him stop at the drugstore to buy a new pair? She would wriggle into it standing beside the car right there in the parking lot, while Gene would lower himself in the front seat, hoping nobody they knew saw them. When she was alive her tendency to make them late had never ceased to frustrate him, but now he looked upon her disorganization with peculiar fondness. Suddenly everything that was hers—the coins that had once been in her pocket, the hour and minute she had last set her alarm—was overburdened with significance. In some mad inversion of time, grieving his wife’s death resembled falling in love.

The most reasonable site he found had been created by an entity who called herself “the Lady in Black.” She said that writing a eulogy was “a personal journey of gathering memories.” She suggested collecting personal items that belonged to the deceased, and “spending time with them until they speak to you—not literally, of course!” Following the Lady in Black’s suggestion, he got up from the computer and went upstairs to the bedroom to find these items.

Excerpted from The Dependents by Katharine Dion. Copyright © 2018 by Katharine Dion. Reprinted by permission of Little, Brown and Company, New York. All rights reserved.

(Photo: Terri Loewenthal)There There

by Tommy Orange

Blood is messy when it comes out. Inside it runs clean and looks blue in tubes that line our bodies, that split and branch like earth’s river systems. Blood is ninety percent water. And like water it must move. Blood must flow, never stray or split or clot or divide—lose any essential amount of itself while it distributes evenly through our bodies. But blood is messy when it comes out. It dries, divides, and cracks in the air.

Native blood quantum was introduced in 1705 at the Virginia Colony. If you were at least half Native, you didn’t have the same rights as white people. Blood quantum and tribal membership qualifications have since been turned over to individual tribes to decide.

In the late 1990s, Saddam Hussein commissioned a Quran to be written in his own blood. Now Muslim leaders aren’t sure what to do with it. To have written the Quran in blood was a sin, but to destroy it would also be a sin.

The wound that was made when white people came and took all that they took has never healed. An unattended wound gets infected. Becomes a new kind of wound like the history of what actually happened became a new kind history. All these stories that we haven’t been telling all this time, that we haven’t been listening to, are just part of what we need to heal. Not that we’re broken. And don’t make the mistake of calling us resilient. To not have been destroyed, to not have given up, to have survived, is no badge of honor. Would you call an attempted murder victim resilient?

When we go to tell our stories, people think we want it to have gone different. People want to say things like “sore losers” and “move on already,” “quit playing the blame game.” But is it a game? Only those who have lost as much as we have see the particularly nasty slice of smile on someone who thinks they’re winning when they say “Get over it.” This is the thing: If you have the option to not think about or even consider history, whether you learned it right or not, or whether it even deserves consideration, that’s how you know you’re on board the ship that serves hors d’oeuvres and fluffs your pillows, while others are out at sea, swimming or drowning, or clinging to little inflatable rafts that they have to take turns keeping inflated, people short of breath, who’ve never even heard of the words hors d’oeuvres or fluff. Then someone from up on the yacht says, “It’s too bad those people down there are lazy, and not as smart and able as we are up here, we who have built these strong, large, stylish boats ourselves, we who float the seven seas like kings.” And then someone else on board says something like, “But your father gave you this yacht, and these are his servants who brought the hors d’oeuvres.” At which point that person gets tossed overboard by a group of hired thugs who’d been hired by the father who owned the yacht, hired for the express purpose of removing any and all agitators on the yacht to keep them from making unnecessary waves, or even referencing the father or the yacht itself. Meanwhile, the man thrown overboard begs for his life, and the people on the small inflatable rafts can’t get to him soon enough, or they don’t even try, and the yacht’s speed and weight cause an undertow. Then in whispers, while the agitator gets sucked under the yacht, private agreements are made, precautions are measured out, and everyone quietly agrees to keep on quietly agreeing to the implied rule of law and to not think about what just happened. Soon, the father, who put these things in place, is only spoken of in the form of lore, stories told to children at night, under the stars, at which point there are suddenly several fathers, noble, wise forefathers. And the boat sails on unfettered.

Excerpted from There There by Tommy Orange. Copyright © 2018 by Tommy Orange. Reprinted by permission of Knopf. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

(Photo: Elena Seibert)

First Fiction 2017

For our seventeenth annual roundup of the summer’s best debut fiction, we asked five established authors to introduce this year’s group of debut writers. Read the July/August 2017 issue of the magazine for interviews between Zinzi Clemmons and Danzy Senna, Hala Alyan and Mira Jacob, Jess Arndt and Maggie Nelson, Lisa Ko and Emily Raboteau, and Diksha Basu and Gary Shteyngart. But first, check out these exclusive readings and excerpts from their debut novels.

What We Lose (Viking, July) by Zinzi Clemmons

Salt Houses (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, May) by Hala Alyan

Large Animals (Catapult, May) by Jess Arndt

The Leavers (Algonquin Books, May) by Lisa Ko

The Windfall (Crown, June) by Diksha Basu

What We Lose

by Zinzi Clemmons

My parents’ bedroom is arranged exactly the same as it always was. The big mahogany dresser sits opposite the bed, the doily still in place on the vanity. My mother’s little ring holders and perfume bottles still stand there. On top of all these old feminine relics, my father has set up his home office. His old IBM laptop sits atop the doily, a tangle of cords choking my mother’s silver makeup tray. His books are scattered around the tables, his clothes draped carelessly over the antique wing chair that my mother found on a trip to Quebec.

In the kitchen, my father switches on a small flat-screen TV that he’s installed on the wall opposite the stove. My mother never allowed TV in the kitchen, to encourage bonding during family dinners and focus during homework time. As a matter of fact, we never had more than one television while I was growing up—an old wood-paneled set that lived in the cold basement, carefully hidden from me and visitors in the main living areas of the house.

We order Chinese from the place around the corner, the same order that we’ve made for years: sesame chicken, vegetable fried rice, shrimp lo mein. As soon as they hear my father’s voice on the line, they put in the order; he doesn’t even have to ask for it. When he picks the order up, they ask after me. When my mother died, they started giving us extra sodas with our order, and he returns with two cans of pineapple soda, my favorite.

My father tells me that he’s been organizing at work, now that he’s the only black faculty member in the upper ranks of the administration.

I notice that he has started cutting his hair differently. It is shorter on the sides and disappearing in patches around the crown of his skull. He pulls himself up in his chair with noticeable effort. He had barely aged in the past twenty years, and suddenly, in the past year, he has inched closer to looking like his father, a stooped, lean, yellow-skinned man I’ve only seen in pictures.

“How have you been, Dad?” I say as we sit at the table.

The thought of losing my father lurks constantly in my mind now, shadowy, inexpressible, but bursting to the surface when, like now, I perceive the limits of his body. Something catches in my throat and I clench my jaw.

My father says that he has been keeping busy. He has been volunteering every month at the community garden on Christian Street, turning compost and watering kale.

“And I’m starting a petition to hire another black professor,” he says, stabbing his glazed chicken with a fire I haven’t seen in him in years.

He asks about Peter.

“I’m glad you’ve found someone you like,” he says.

“Love, Dad,” I say. “We’re in love.”

He pauses, stirring his noodles quizzically with his fork. “Why aren’t you eating?” he asks.

I stare at the food in front of me. It’s the closest thing to comfort food since my mother has been gone. The unique flavor of her curries and stews buried, forever, with her. The sight of the food appeals to me, but the smell, suddenly, is noxious; the wisp of steam emanating from it, scorching.

“Are you all right?”

All of a sudden, I have the feeling that I am sinking. I feel the pressure of my skin holding in my organs and blood vessels and fluids; the tickle of every hair that covers it. The feeling is so disorienting and overwhelming that I can no longer hold my head up. I push my dinner away from me. I walk calmly but quickly to the powder room, lift the toilet seat, and throw up.

From What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons, published in July by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2017 by Zinzi Clemmons.

(Photo: Nina Subin)Salt Houses

by Hala Alyan

On the street, she fumbles for a cigarette from her purse and smokes as she walks into the evening. She feels a sudden urge, now that she is outside the apartment, to clear her head. This is her favorite thing about the city—the ability it gives you to walk, to literally put space between your body and distress. In Kuwait, nobody walks anywhere.

Mimi lives in a quiet part of the city, mostly residential, with small, pretty apartments, each window like a glistening eye. The streetlamps are made of wrought iron, designs flanking either side of the bulbs. There is a minimalist sense of wealth in the neighborhood, children dressed simply, the women always adjusting scarves around their necks, their hair cut into perfectly symmetrical lines. Souad walks by the manicured lawns of a grammar school, empty and discarded for the summer. Next to it a gray-steepled church. She tries to imagine that, elsewhere, there is smoke and destroyed palaces and men carrying guns. It seems impossible.

The night is cool, and Souad wraps her cardigan tightly around her, crosses her arms. A shiver runs through her. She is nervous to see him, a familiar thrill that he always elicits in her. Even before last night.

Le Chat Rouge is a fifteen-minute walk from Mimi’s apartment, but within several blocks the streets begin to change, brownstones and Gothic-style latticework replaced with grungier alleyways, young Algerian men with long hair sitting on steps and drinking beer from cans. One eyes her and calls out, caressingly, something in French. She can make out the words for sweet and return. Bars line the streets with their neon signs and she walks directly across the Quartier Latin courtyard, her shoes clicking on the cobblestones.

“My mother’s going to call tomorrow,” she told Elie yesterday. She wasn’t sure why she said it, but it felt necessary. “They’re taking me to Amman.” In the near dark, Elie’s face was peculiarly lit, the sign making his skin look alien.

“You could stay here,” Elie said. He smiled mockingly. “You could get married.”

Souad had blinked, her lips still wet from the kiss. “Married?” She wasn’t being coy—she truthfully had no idea what Elie meant. Married to whom? For a long, awful moment, she thought Elie was suggesting she marry one of the other Lebanese men, that he was fobbing her off on a friend in pity.

“Yes.” Elie cocked his head, as though gauging the authenticity of her confusion. He smiled again, kinder this time. He closed his fingers around hers so that she was making a fist and he a larger one atop it. They both watched their hands silently for a few seconds, an awkward pose, more confrontational than romantic, as though he were preventing her from delivering a blow. It occurred to her that he was having a difficult time speaking. She felt her palm itch but didn’t move. Elie cleared his throat, and when he spoke, she had to lean in to hear him.

“You could marry me.”

Now, even in re-creating that moment, Souad feels the swoop in her stomach, her mouth drying. It is a thing she wants in the darkest, most furtive way, not realizing how badly until it was said aloud. Eighteen years old, a voice within her spoke, eighteen. Too young, too young. And her parents, her waiting life.

But the greater, arrogant part of Souad’s self growled as if woken. Her steps clacked with her want of it. The self swelled triumphantly—Shame, shame, she admonishes herself, thinking of the war, the invasion, the troops and fire, but she is delighted nonetheless.

From Salt Houses by Hala Alyan. Copyright © 2017 by Hala Alyan. Used by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

(Photo: Beowulf Sheehan)Large Animals

by Jess Arndt

In my sleep I was plagued by large animals—teams of grizzlies, timber wolves, gorillas even came in and out of the mist. Once the now extinct northern white rhino also stopped by. But none of them came as often or with such a ferocious sexual charge as what I, mangling Latin and English as usual, called the Walri. Lying there, I faced them as you would the inevitable. They were massive, tube-shaped, sometimes the feeling was only flesh and I couldn’t see the top of the cylinder that masqueraded as a head or tusks or eyes. Nonetheless I knew I was in their presence intuitively. There was no mistaking their skin; their smell was unmistakable too, as was their awful weight.