'Could Care Less' Versus 'Couldn't Care Less'

When people tell me their pet peeves, they often mention the phrase “could care less.” They claim it should be “couldn’t care less.”

“It’s illogical. If you could care less, you still care. Don’t people get it?” they say.

Celebrities have even jumped on the cranky bandwagon. Both David Mitchell and John Cleese have made popular YouTube videos ranting about the illogical phrase “could care less.” Interestingly, both men are British comedians, and they’re both complaining, in particular, about Americans who use the phrase.

Do Americans Say ‘Could Care Less’?

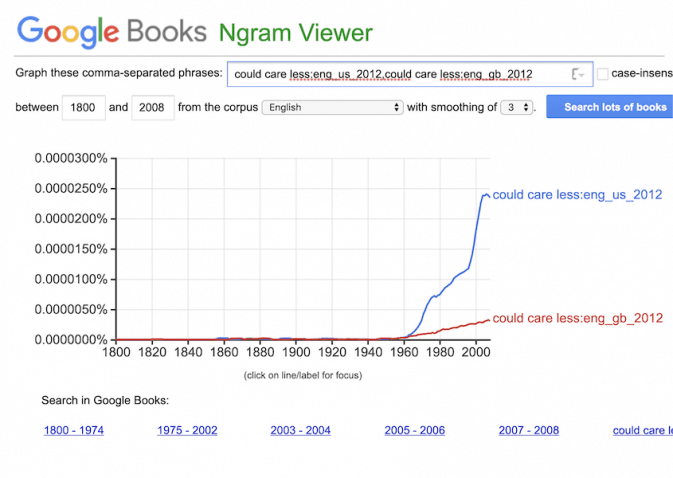

Are Americans really more likely to say they could care less? It appears so, at least when you look at how often that phrase shows up in American books Google has scanned versus British books Google has scanned. It shows up a lot more often in the American books.

That could mean that Americans use it more, or it could mean that British editors are more strict about changing “could care less” to “couldn’t care less.” But the Oxford English Dictionary calls “could care less” a “U.S. colloquial phrase,” and the linguist Lynne Murphy, who blogs about the differences between British and American English, also notes that Americans say “could care less” far more often than the British.

I think we’re busted! Maybe we Americans are just more caring, so that even when we’re annoyed, we reserve some caring just in case we want to use it later. But probably not.

The Origins of ‘Could Care Less’ and ‘Couldn’t Care Less’

The phrase “I…