Managing Submissions in the Age of AI

Last July, shortly after announcing that Lillian-Yvonne Bertram’s speculative essay collection, A Black Story May Contain Sensitive Content, had won Diagram’s 2023 chapbook contest, editor Ander Monson received a raft of text messages from concerned friends. He discovered that he and Diagram, a literary magazine that publishes chapbooks through New Michigan Press, were being excoriated on X (formerly Twitter) because Bertram had created the chapbook using artificial intelligence (AI).

“So many people were attacking us and Lillian-Yvonne for what they thought was an ethical breach,” Monson says. “They heard ‘AI-written book wins literary contest,’ which is not exactly what happened.” While Bertram did use AI, it was explicitly to engage the technology in an artistic experiment: Bertram employed a process called “fine-tuning” with GPT-3, the technology underlying the ChatGPT chatbot, in which they fed it text by Gwendolyn Brooks to shift the AI engine’s linguistic “tone and approach,” as Bertram put it in the introduction to their chapbook. They then repeatedly prompted GPT-3 to “tell me a Black story.” Each time, GPT-3 came back with a different, often fascinating reply. Bertram lightly edited the most compelling responses for inclusion in the book.

“People had thought I’d intentionally tried to fool Diagram by submitting AI work,” Bertram says. “But Diagram knew what the project was. I wasn’t trying to fool anyone.”

Bertram’s case points to questions that editors and literary organizations are increasingly wrangling with as they face a rise of AI-generated and -enhanced submissions: Should they allow authors to use AI, and, if so, what counts as an acceptable use of the technology versus cheating? How can they weed out illegitimate AI submissions, not only for contests, but also during regular reading periods?

Sci-fi magazine Clarkesworld bans all submissions that have been touched by AI. “We consider them the fruit of a poisoned tree,” says Neil Clarke, the magazine’s publisher and editor in chief. He’s referring to the alleged training of AI on pirated text, which has spurred copyright-infringement lawsuits by the Authors Guild—a writer-advocacy organization—and numerous writers.

Mary Gannon, executive director of the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP), recommends magazines take a stance on AI and make it explicit in their submission guidelines, whether forbidding such tools or requiring disclosure of their use. She also suggests that publications consider other options to deal with AI, such as requiring authors to confirm during the submission process that AI was not used or testing suspect work with detection tools like Copyleaks or GPTZero, which charge rates between $8 and more than $20 per month, depending on the level of service.

“The big issue is whether or not an author is being transparent about the origin of the work,” Gannon says. In January, for example, author Rie Qudan, winner of Japan’s prestigious Akutagawa Prize for her novel, Tōkyō-to Dōjō Tō (Tokyo Sympathy Tower), revealed at the award ceremony that about 5 percent of the book used verbatim language from ChatGPT.

Also in January, Jessica Bell, publisher of Vine Leaves Press in Athens, Greece, discovered an AI-generated memoir submission in the slush pile. She was taken with the query letter, from someone claiming to be a disabled man “who had gone through quite a bit of hardship.” But the sample pages were a dry how-to manual for surviving hardship, not the promised memoir. When she discovered that he had published more than ten books on Amazon in two months, she became suspicious and checked the memoir text with Copyleaks, which confirmed that the sample pages were AI-generated.

Bell decided to change the press’s submission guidelines, stating that AI-written submissions “will be rejected.” But, she says, “I fear that it’s not going to stop people.”

When Christine Stroud, editor of Pittsburgh-based Autumn House Press, heard about the Vine Leaves AI submission on an online forum through which CLMP members communicate, she revised Autumn House’s submission guidelines to forbid work generated or supported by AI. She had heard about the rise of AI-supported academic papers but had not realized literary writers would submit AI-generated work. “It was perhaps naive of me to assume folks were not doing it,” she says.

Some magazines, like Clarkesworld, have been inundated with AI submissions that are essentially spam. Clarke believes that charging a reading fee would deter these submissions. (Most contests do require a fee, though many regular magazine or book submissions do not.) But a fee could further marginalize already burdened populations, especially in communities that are geographically isolated—from which Clarke, for one, has been trying to cultivate submissions. Not only can even a few dollars be prohibitive for such communities, but credit cards may be unavailable to them. Short submission windows can be an alternative deterrent for AI fraudsters, says Clarke. But he has resisted shortening Clarkesworld’s reading period—despite receiving thousands of AI-generated submissions—because that step, too, would make it less likely for some overseas writers to contribute.

Clarke also avoids AI detection tools like GPTZero because, as a 2023 Stanford study showed, they are more likely to erroneously flag writers for whom English is not their first language.

Still, the fight against AI is only getting harder. Clarkesworld has banned several thousand individuals for submitting AI-generated stories and fields more AI-generated submissions as time goes on, says Clarke. He says he might reconsider the magazine’s stance against such submissions when AI systems are ethically trained, but he doubts he will change his mind even then—unless the quality of the writing improves. “A good story works on multiple levels, and an AI story doesn’t. It doesn’t know what it’s writing.”

Jonathan Vatner is the author of The Bridesmaids Union (St. Martin’s Press, 2022) and Carnegie Hill (Thomas Dunne Books, 2019). The managing editor of Hue, the magazine of the Fashion Institute of Technology, he teaches fiction writing at New York University and the Hudson Valley Writers Center.

ChatGPT Revises Authorship

Want a poem in the style of Frank O’Hara or a story in the style of Flannery O’Connor? Your wish is ChatGPT’s command: Just send the request and the words unfurl across your screen. In about thirty seconds, ChatGPT can unleash a 494-word “Flannery O’Connor–style” story about a quiet, plain-looking girl in a small Southern town hurling a Bible at a preacher’s head. A five-stanza “Frank O’Hara–style” poem, rhapsodizing the bustle of music and strangers on city sidewalks, takes ChatGPT less than fifteen seconds to write.

A chatbot created by the San Francisco–based research lab OpenAI, ChatGPT was released for use by the general public in November. Although artificial intelligence (AI) has been in development for decades, ChatGPT has struck a cultural nerve—particularly among those who make their living with language. ChatGPT’s learning model was trained on a mind-boggling 570 gigabytes of text, mostly English-language material from various sources and time periods. With powerful algorithms, ChatGPT uses a probability-based language-prediction model to generate each word in a sentence, producing coherent content in a conversational tone. Its poems and stories demonstrate an understanding of basic narrative structure and different genres while also incorporating customizable details about setting, style, and character.

These capabilities have raised fears that AI could render the human writer obsolete. ChatGPT has, indeed, already replaced some human authors for a certain set of readers. Through Amazon’s Kindle Direct Publishing program, users have been selling AI-generated picture books and quick-premise, high-concept works of “literature.” In February, Reuters reported that there were more than “200 e-books in Amazon’s Kindle store as of mid-February listing ChatGPT as an author or co-author.” And there may be more than that, since Amazon does not require writers to “disclose in the Kindle store that their great American novel was written wholesale by a computer,” according to Reuters.

For teachers of writing, many of whom are writers themselves, ChatGPT also poses concerns. Commentators have written diatribes about ChatGPT’s threat to education in publications such as the Atlantic and the Chronicle of Higher Education. Some have discovered that students are turning in assignments written by AI that contain factual errors and that they present as their own original thinking. It stands to reason, however, that creative writing students derive pleasure from the writing process, and so there may be less incentive for them to turn in an AI-generated story or poem to a workshop.

If the existential threat posed by ChatGPT to authorship is overblown, it has already caused havoc in parallel realms. In February the popular sci-fi magazine Clarkesworld announced that it would have to temporarily close to submissions because of an influx of AI-generated stories. Neil Clarke, Clarkesworld’s publisher and editor, tweeted about the decision, saying he thought the phenomenon was financially driven: With a pay rate of 12 cents per word and stories of as many as 22,000 words, Clarkesworld authors can earn $2,640 per story.

It’s not clear how lower-paying or nonpaying magazines will be affected, but editors of those publications are talking about it on the online member forum of the Community of Literary Magazines and Presses (CLMP). “We’ve decided to proactively ban the use of AI in works we publish unless specifically invited,” wrote Joshua Wilson, editor and publisher of the Fabulist. “Along with this stated policy, we’ve also updated our contract to include a no-AI section.” Miracle Jones, an editor at Epiphany and a contributing editor at the Evergreen Review, suggested that nominal submission fees could thwart people from running blanket-submission schemes with AI-authored work. And new apps designed to detect AI-generated writing, such as GPTZero, could help overwhelmed editorial staff by filtering such submissions.

Not all editors are raising red flags, though. Liza St. James, a senior editor at Noon, said the uproar over ChatGPT has prompted her to think about Oulipian constraint-based practices. “I guess my first thought is that if a bot-generated text merits publishing, we would likely credit the human who called it forth from the machine—who made it exist in the first place,” she wrote in an e-mail. “Most published works are already the result of some amount of collaboration. Why not find creative ways to embrace this, or even to showcase it?”

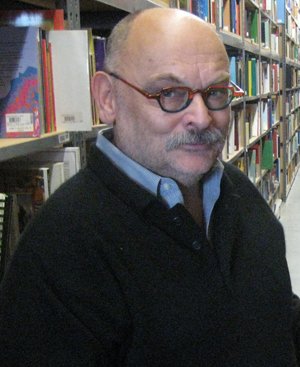

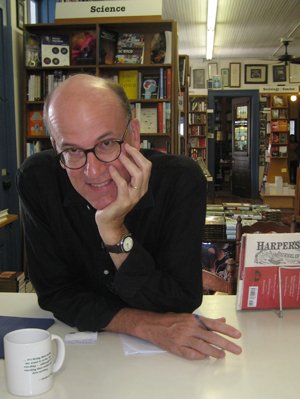

“I want to be open-minded about what imaginative people can do with new tools,” Jacob Smullyan, founding editor of Sagging Meniscus Press, wrote on the CLMP forum. “One reaction I hope to see is a critique of human practice akin to how artists reacted to photography. How much of what we already do is revealed by these new tools to have less inherent dignity, to be already mechanical and superficial?”

Writers dazzled by ChatGPT, however, may not be aware of the potentially harmful biases embedded within the texts it generates. When I asked the chatbot directly about the kind of texts it draws from, it told me that the majority was “likely to be from the public domain.” For books, that typically refers to volumes published in the first two decades of the twentieth century and earlier. “It is possible that a large portion of the literature in the public domain was written by white male authors, especially in earlier time periods when women and people of color had fewer opportunities to publish their work,” ChatGPT conceded. This is troubling because it means that ChatGPT’s language algorithm contains all the biases, including racist and sexist tropes, entrenched within older literature. (I requested a story “written in the style of Raymond Carver, if he were Chinese” and received as a first sentence: “He looked at the bowl of rice in front of him, feeling empty and lost.”)

Margaret Rhee, a feminist scholar and new media artist and poet, conjectured that writers who are new to experimenting with AI might not have thought about the ethical implications of working with biased technology, which should be reckoned with for a project to be effective. Often the best AI-assisted projects, Rhee said, will have a turn of some kind, using technology to serve a subversive agenda. One example is artist Rashaad Newsome’s recent “Digital Griot” projects, in which Newsome trained a chatbot with texts by writers such as bell hooks and James Baldwin, allowing users to move through indexes, archives, and history in a counter-hegemonic way.

In the New York Times and MIT Technology Review, various people associated with OpenAI and Microsoft’s Bing chatbot have said that the only way to continue improving AI technology is to release versions that are bound to make mistakes, which they will then address. AI is a new frontier, after all, with the many challenges and unimagined outcomes—both troubling and exciting—that a new frontier entails.

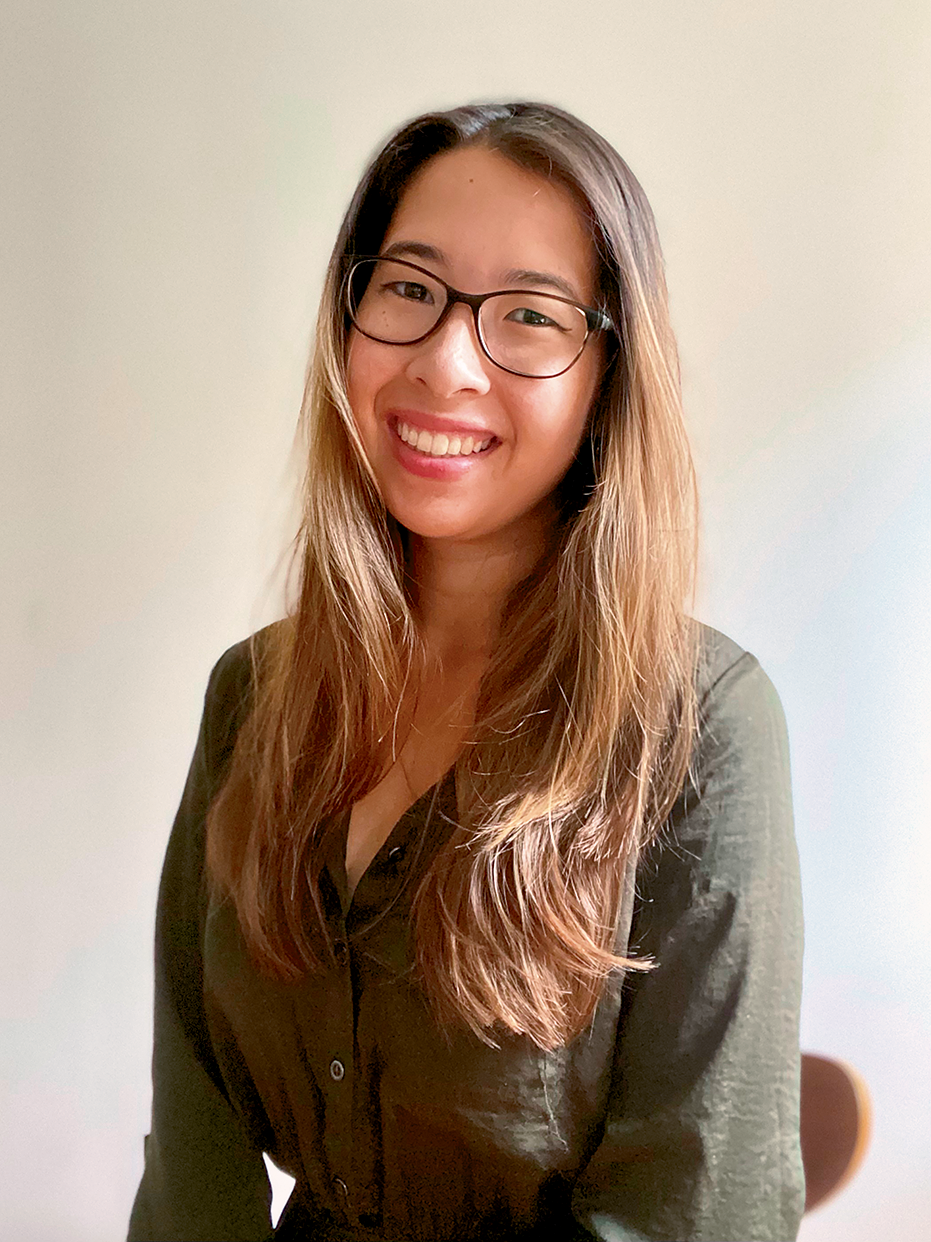

Bonnie Chau is the author of the short story collection All Roads Lead to Blood (Santa Fe Writers Project, 2018). She currently serves on the board of the American Literary Translators Association, teaches fiction writing and translation at Columbia University and Fordham University, and edits for 4Columns, Public Books, and the Evergreen Review.

Audience for Audiobooks Grows

Last year, Randye Kaye, an author and prolific audiobook narrator, was looking to create audio versions of her own two books, Happier Made Simple: Choose Your Words. Change Your Life, which she self-published with Ignite Press, and Ben Behind His Voices: One Family’s Journey From the Chaos of Schizophrenia to Hope, a memoir she published with Rowman & Littlefield.

Kaye’s motivation was to tap into a growing market for authors: Audiobooks “can reach an entire audience who might not have been able to find the time to sit down and read the book,” she says.

Indeed, audiobook revenue grew 25 percent in 2021 to $1.6 billion, the tenth straight year of double-digit growth, according to the Audio Publishers Association. In 2011, 7,237 audiobooks were produced; by 2021 that number rose more than tenfold to 73,898. While those figures do not differentiate between small and large publishers, more independent authors are trying their hand at audiobook production, says Michele Cobb, executive director of the Audio Publishers Association.

For Kaye’s audiobooks, Ignite Press suggested that she try Findaway Voices. Launched in 2016, this service enables anyone to produce professional audiobooks and distribute them through more than forty outlets, including Audible, the biggest name in audiobooks; Google Play; Libro.fm, which shares proceeds with independent bookstores; Chirp, which promotes discount audiobooks to a large audience; and OverDrive, which distributes to libraries. Another popular choice for independent authors and presses is ACX, a subsidiary of Audible, which is owned by Amazon. Both companies help authors cast a narrator and automate the distribution process, but Findaway Voices offers a higher royalty rate. ACX offers a comparable rate only if authors agree to distribute exclusively through Audible, Amazon, and iTunes.

Although Kaye had narrated a handful of audiobooks by other authors through ACX, she chose Findaway Voices for her books. “ACX can be fabulous—they offer a lot of help for authors,” she says. But she wanted wide distribution without sacrificing royalties.

Kaye may soon have a bigger audience than she expected. This past September, Findaway Voices titles became available on Spotify; the audio-streaming giant purchased parent company Findaway in June 2022 to add audiobooks to its music-streaming business. Findaway’s distribution arm allows any publisher to sell audiobooks on Spotify, from the Big Five through independent presses and authors. Findaway Voices is being touted as the smoothest route for the latter to get their audiobooks to Spotify, though authors can use any company willing to distribute through Findaway and Spotify.

Kaye, who is now working on advertising and marketing to boost her audiobook sales, is happy about the additional retail channel. “I’m not sure what it will do to the personal nature of Findaway, but as long as they continue to be professional and friendly, it doesn’t bother me.”

The move by Spotify to add Findaway not only expands the audience for audiobooks, but it also promises special features. A new section in the Spotify app lets users browse a library of 300,000 audio titles for purchase, allowing users to download books to their device, speed up or slow down the narration, pick up where they left off, and rate books they’ve completed. Spotify has not offered a streaming subscription for audiobooks, as the company does for music; each title must be purchased separately.

Spotify has not planned to create any exclusive contracts for audiobooks, so authors using Findaway Voices should still be able to sell through other outlets.

Cobb interprets Spotify’s entry into the audiobook market as good news for authors and publishers: “The Spotify listener is not the traditional book consumer, which might bring people who have never listened to an audiobook to the format.”

Cory Doctorow, coauthor of Chokepoint Capitalism: How Big Tech and Big Content Captured Creative Labor Markets and How We’ll Win Them Back (Beacon Press, 2022), is more skeptical of Spotify’s intentions. He points out that many podcasters lost significant portions of their audience when Spotify bought their podcasts and made them exclusive to its streaming platform. “It’d be pretty naive to think the way Spotify treats authors is better than the way they treat podcasters,” he says.

Overall, though, Doctorow believes Spotify’s foray into audiobooks is a step in the right direction. The added competition may even nudge Audible toward loosening restrictions—known as digital rights management, or DRM—that prevent its audiobooks from being listened to on other platforms. “If the alternative to Audible is nothing, then it can treat creators really badly. If there’s an alternative like Spotify, it’ll treat them better.”

Jonathan Vatner is the author of The Bridesmaids Union (St. Martin’s Press, 2022) and Carnegie Hill (Thomas Dunne Books, 2019). He is the managing editor of Hue, the magazine of the Fashion Institute of Technology, and teaches fiction writing at New York University and the Hudson Valley Writers Center.

In Conversation With Garth Greenwell, Audible and Publishers Reach Settlement, and More

Every day Poets & Writers Magazine scans the headlines—publishing reports, literary dispatches, academic announcements, and more—for all the news that creative writers need to know. Here are today’s stories.

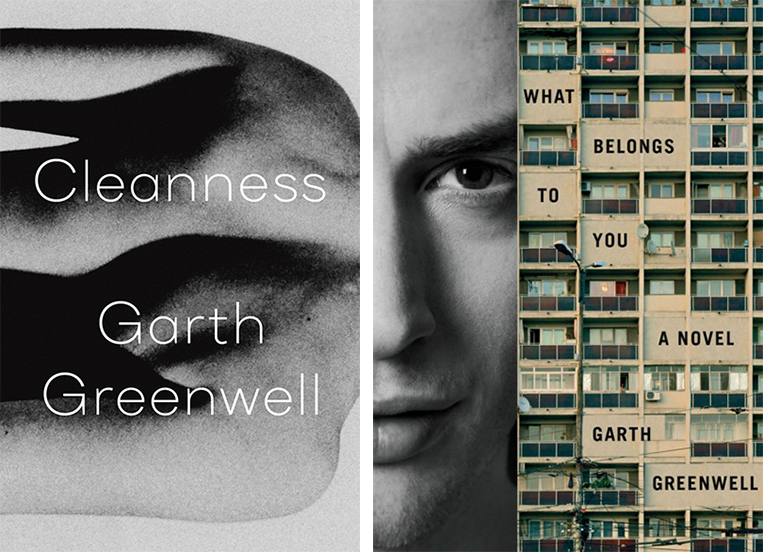

“Almost all of our lives and thinking exist in spaces of ambiguity, uncertainty and doubt,” says Garth Greenwell. “Art seems to me precisely the tool we have for allowing ourselves the fullness of human thinking.” In a new conversation with Amy Gall, Greenwell talks writing process, politics and public life, sex and love. His second book of fiction, Cleanness, was published yesterday by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. (Poets & Writers Magazine)

Attorneys for Audible have announced the company will settle with the seven publishers who filed a lawsuit against the audiobook giant in August last year. The plaintiffs, which include all of the “Big Five” houses, had submitted that a new in-app feature, Audible Captions, violated copyright by generating unauthorized text. The terms of the settlement have not yet been disclosed, but documents are expected by January 21. (Guardian)

Having just completed ten years at Henry Holt, Steve Rubin shared that he will be leaving his position as chairman. “My time here has been among the happiest in my career,” Rubin says. (Publishers Lunch)

Belarusian writer and Nobel Laureate Svetlana Alexievich plans to launch a new press exclusively dedicated to publishing women writers. Works by Eva Veznavets and Tatyana Skorkina will be among the first titles. (Calvert Journal)

The Atlantic has announced it will begin to publish fiction “with far greater frequency than we’ve managed in the past decade.” “Birdie” by Lauren Groff is kicking off the new editorial initiative.

Jeanine Cummins talks to the New York Times about her forthcoming book, American Dirt, and the risks and responsibilities of writing from the perspective of Mexican migrants as someone far removed from their world.

Jenny Odell reflects on a fortuitous encounter with Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essays, and what reading the transcendentalist taught her to see in her own writing. “Hard as I might work, I will be anything but self-made.” (Paris Review Daily)

Book Marks anticipates eleven titles by Indigenous authors set for release in the first half of 2020.

Cleanness by Garth Greenwell

Garth Greenwell reads from his novel-in-stories, Cleanness, published in January 2020 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

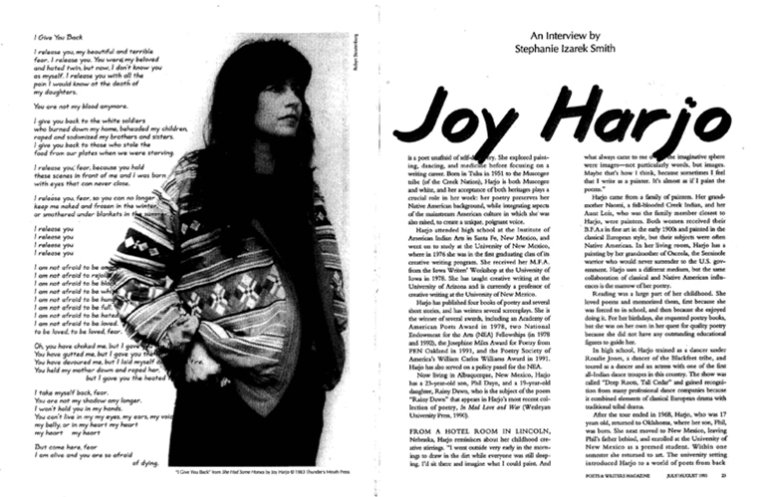

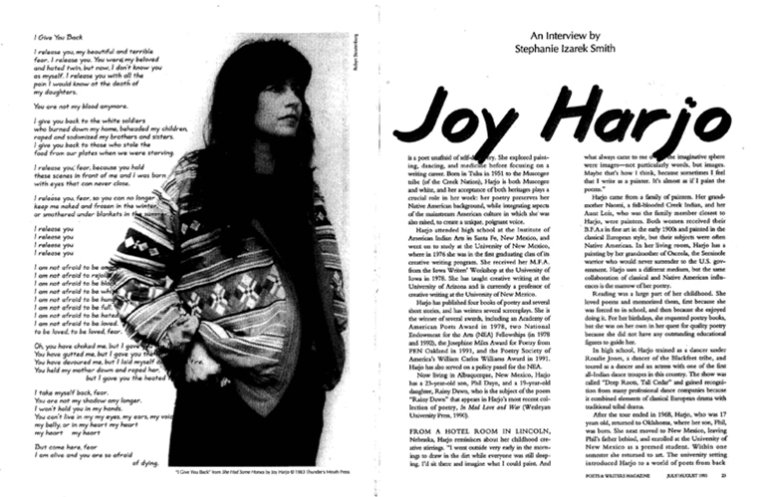

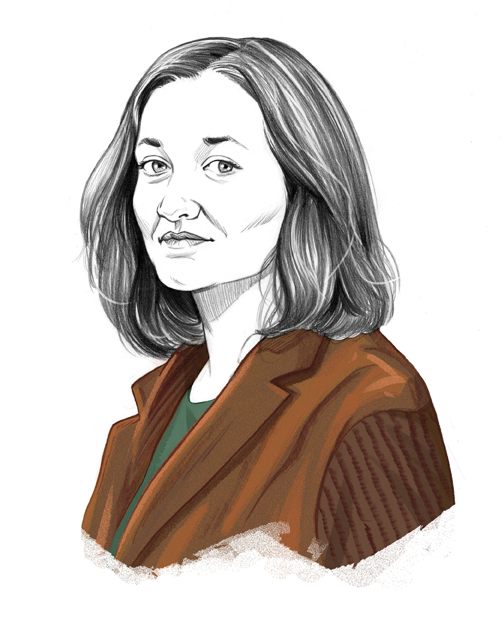

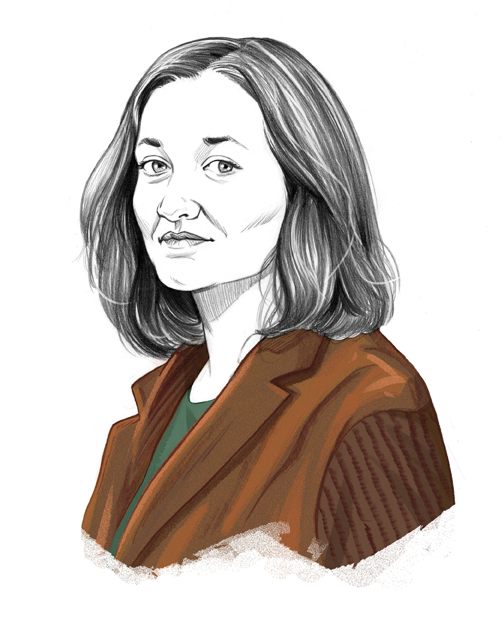

Dialects of Desire: A Q&A With Garth Greenwell

Garth Greenwell isn’t interested in creating literary heroes. “There is a kind of luxury in narratives where the moral calculus is clear. I think it’s one of the reasons why we’re still so addicted to World War II dramas,” he says. “That was the last moment where we felt like the good guys and the bad guys were really obvious. But we don’t live in a world like that and we don’t inhabit selves in which goodness and badness are clear.”

There is perhaps no better example of Greenwell’s love of moral complexity than his wildly successful debut novel, What Belongs to You (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), which was long-listed for the National Book Award, named one of the best books of the year by more than fifty publications, translated into a dozen languages, and hailed as an “instant classic” by the New York Times Book Review. Though it is a work of fiction, What Belongs to You was, in part, inspired by Greenwell’s four-year stint as an English teacher at the American College of Sofia in Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013. The book explores a relationship between an unnamed, closeted American narrator teaching English at a high school in Sofia and his lover, Mitko, a young, broke, local hustler whom the narrator picks up in a public bathroom. What on its face might have seemed like a narrative of clear “moral calculus” was, in fact, a deeply nuanced exploration of sexuality, class, and citizenship.

But as Greenwell worked on What Belongs to You he kept having to set aside characters and storylines that fell beyond its scope. His new novel, Cleanness, out now from FSG, returns to the world of the narrator but allows readers a much fuller picture not only of his life but that of the citizens of Sofia and their dual struggle for identity and purpose. “It’s not like one book is a sequel or a prequel,” Greenwell says. “They’re promiscuous with each other,” with events in Cleanness happening before during and after those that take place in What Belongs to You. Each chapter in Cleanness functions as its own stand-alone story. In one, the narrator listens to the painful coming-out tale of one of his students which echoes back to his own doomed first love. In another, he meets his friends for a political protest and witnesses comradery, hope, and an incident that reminds him of the incredible precariousness of peace. In the central chapters of the novel, we witness the narrator fall in love with R, a fellow closeted man he meets online, with whom he experience new levels of trust and intimacy. We also watch the narrator engage in a sexual encounter with a stranger that nearly ends in his death. But each chapter continues to twist and complicate any easy judgements we might make about the characters we meet. And in turn it asks us to make room for contradiction and change in our own lives and to look at each other, not as heroes or villains but as humans.

Though he is best known for fiction, Greenwell got his start as a singer, having trained in opera beginning in high school, before moving on to poetry, criticism, and essay writing. Having moved back to the United States in 2013, he continues to balance a life of writing with a life of teaching in Iowa City, where he is a visiting professor at the prestigious Iowa Writers’ Workshop.

I spoke to Garth shortly before his book’s release about the uneasy marriage of capitalism and sex, the future of democracy, and, of course, love.

What I love so much about this book—and your writing in general—is how little you moralize sex that includes pain or violence or an embodiment of a kind of toxic masculinity. You leave readers feeling like maybe this kind of sex is healing, or maybe it reinforces shame, or maybe it’s both, but there’s a lot of breathing room for contradiction.

I think the earliest really explicit piece of the book I wrote was “Gospodar” [which involves a sadomasochistic encounter the narrator has with a stranger in Sofia]. I remember as I was writing that feeling like I really wanted to get at a certain experience of sex that I wasn’t sure I had seen represented, and to get there, it required a commitment to explicitness and a lack of squeamishness and concern about audience. I had to write things that would be off-putting and disturbing to many people. But I wanted this experience of rawness and explicitness to be paired with a very high art feeling and all of the filters of consciousness and literary tradition. That was exciting to me, and I was trying to write in a way that gave me access to both of those things.

I hope that the book doesn’t offer any single message about sex or the kind of sex the narrator seeks out. The argument the book makes is sex is all of those things and sex is always going to present dilemmas that outpace any moral calculus we might bring to them. I think that’s true of a lot of things in human life and that doesn’t exempt us from responsibility or the necessity to hold ourselves accountable but it refuses us the luxury of any too-easy accounting.

It does feel like there is something more self-aware and therefore more connected about the narrator’s sexual relationships in Cleanness.

I believe this is a much more social book than What Belongs to You—there are so many more characters and the narrator has many more relations. I know the bar is set in a different place, but to me this is also a much happier book and there are more moments when someone intervenes in the narrator’s ratiocination and kind of gives him a way out, especially in the central love story with R. In some way the book wants to posit that one of the things love is, is a way of opening a door for the other and giving the other relief.

Is that what you think love is?

I do use fiction to think. One of the things I think narrative can very powerfully do is test ideas in a kind of reality simulation. In What Belongs to You the narrator had previously thought that attention is love, that to look at something and attend to it is a form of love. But he revises that and says love is not looking at someone but looking with someone and facing what they face. And it led me to a moment where I was like, I do think that’s true.

I feel like it will be years before I know whether something similar happened with this book, but I do think that one of the things we do as lovers is recontextualize one another’s lives. I would not want to turn it into something tritely optimistic—and I’m always skeptical of open doors or whether an open door will ever lead anywhere other than another room that will eventually feel as stifling as the ones we were in before—but that experience of opening out to someone else is exhilarating.

You mentioned “Gospodar,” which was originally published as a stand-alone story, as were some of the other chapters in this book. I’m curious how you approached structuring those pieces, because the book feels so seamless.

There was a lot of revision. There were surface-level revisions of repetitions across previously published pieces that I took out, but then the big question was putting the pieces in relationship in the larger structure and figuring out how time would work across the book as a whole. I knew I didn’t want the book to be chronological. I wanted there to be relationships that were more mysterious and out of time. But then I wanted something chronological at the heart of the book. It felt important to me for the three R chapters, and for that central love story to have a beginning and a middle and an end. But then the first and third parts I found myself realizing I wanted to have a kind of mirroring structure, where they were resonating with each other but also showing very different reflections of the narrator and his experiences in Sofia.

And then when it came time to put a label on the book there was the question of what we called it. Is it a novel? Is it a story collection? I finally felt like neither of those were right to me. Cleanness really feels, to me, like a book of fiction which is how FSG is publishing it, which makes me really happen and readers can think of it however they want.

I know it’s been a while since you wrote poetry, but do you think poetry allows you to make bolder structural choices with fiction?

I very much feel that poetry is akin to sculpture, and that I was carving language out of silence and trying to exempt language from time. I wanted to take a thought and make it suspended in white space. But that eventually came to feel kind of stifling to me. I sweated so much over individual words and over feeling like I had to choose the words that would kind of open in this infinite way and be infinitely resonant, and in prose I don’t feel the same anxiety about finding the precise single word because I’m so often drawn to syntax that says this or this, or some combination of this and this and this. I think both of those strategies [in poetry and prose] are after the same thing, which is amplitude and resonance. But the reason I’ve kept writing prose and haven’t yet returned to poetry, although I would love to, is there’s something exciting and surprising about the very un-sculptural movement that the kind of sentences I’m drawn to allow for.

There’s a kind of musicality in your prose, I think. The way the words rise and fall, the kind of drama of each sentence. I know you were an opera singer in your younger life, do you feel like you take that practice to the page, too?

Music is endlessly inspiring to me. I don’t listen to music when I’m writing but I reach for musical analog for an effect I want in writing. Because of the training I had in the Bel Canto tradition, one of the lessons I take with me into writing is the fact that language is something that exists in our body. It has materiality and corporeality. And in a way that’s not so different from poetry; opera can show you the way that emotions can be generated by suspending language in time. An aria takes very few words and suspends them over great distances, and there’s a way in which that itself becomes a kind of expression or embodiment of desire.

But I also find inspiration in painting, film, theater, dance. Sometimes a particular artist becomes crucial to a project. My partner is Spanish, and we were in Madrid while I was editing What Belongs to You. There was a wonderful El Greco exhibition at the Prado, and I went almost every day, usually sitting for an hour or so in front of a single painting. I can’t really articulate why, but it was helpful. Maybe it’s that El Greco’s paintings so often seem to make artistic struggle visible; sitting with them gave me a weird sense of solidarity.

What is your writing schedule like? Is that something that also gives you a sense of solidarity?

When I was working as a high school teacher, the only way I could be productive was to have a strict schedule: I wrote from 4:30 to 6:30 every morning. I still like to write first thing in the morning. Routines are important for me, and I find it hard to work well when I’m in an unsettled situation: traveling, say. My partner and I bought a house recently, and my writing room is the garage, which the previous owner converted into an artist’s studio. On warm days, if I keep the door open, a neighbor’s cat will come in to say hello: the best distraction.

I also can’t work with a word or page count: It makes me miserable to feel that I have to meet some metric of productivity. Anytime I have a deadline it takes over my life; I hate deadlines. The only metric that matters for me is time: I have to be at my desk, doing nothing else, for a certain amount of time. I write by hand, and keep all screens in another room. I tell myself that it doesn’t matter if I don’t write a word: As long as I sit with my notebook for a certain number of hours, I’ve done my work.

To go back to what you said about Cleanness being a “more social” book, I also think this book gives a larger sense of what it takes for gay men to navigate relationships in Sofia. Has the situation for LGBT folks in Bulgaria in general changed or improved since your time there?

I don’t want to pretend to speak about that authoritatively because I do feel further and further away from life on the ground. When I was teaching at the American College of Sofia (ACS), I and a few other faculty members and a very passionate group of students tried to start a Gay Straight Alliance, and that was stamped out by the administration. So we had a club that was about human rights in a kind of generic way that was really a gay club even though we couldn’t call it that. But, shortly after I left, the campaign was continued by Garrard Conley, author of the book Boy Erased, and other faculty. And a couple years ago ACS became the first high school in the Balkans with a GSA.

At the same time, my sense is that the increasing influence of Putin in that part of the world has made gains achieved by queer people feel very provisional and perilous. I was in Bulgaria from 2009 to 2013, and for the first three years there was a feeling of incredible progress around LGBT rights and visibility and then around 2012 it felt like this very concerted pushback campaign in which conservative politicians and the Orthodox church began speaking in unison with Putin about gay propaganda. Which, let’s acknowledge, is very much what’s happening in the United States right now on all fronts.

Yes, the protest chapter in Cleanness felt like it contained a really familiar urgency. In what ways have your experiences of political protest in Bulgaria been similar or different to your experiences in the United States?

I had never experienced anything in the United States that felt like what was happening in Bulgaria in 2013 with these enormous street protests across the country. You really did feel like all of Sofia was in the streets. There was also a kind of extremity that I have not seen in the United States. I think it was six people set themselves on fire in protest of conditions, and that kind of public martyrdom is not something we’ve experienced on that scale in the United States. But seeing the kind of misinformation campaigns and meddling on the part of Putin that happened in America in 2016 really felt like a kind of deja-vu. Again, I’m not qualified to make this statement, but it does feel like what Putin has been doing in the West by encouraging chaos is something he had been doing in the area of former Soviet influence for a long time.

What was most surprising to me about the protest scene in Cleanness is that it did not erupt in violence.

One of the things that I wanted to explore in that chapter was the feeling of contingency, that at any moment what is a kind of haloed expression of democracy could become violent and that there were elements really trying to create that chaos. This is something I feel very strongly happening in the United States. I believe in the institutions and traditions of liberal democracy, not because they have ever been perfect but because they offer us the best mechanisms we have ever devised as human beings for addressing wrongs. It terrifies me how close we are to the brink of letting those institutions fall away and how that is a crisis coming from all sides.

I think there is active malevolence and an active desire to destroy those institutions in favor of a kind of authoritarianism and state violence coming from the right. And then from the left I think there is an entire loss of faith and confidence in the idea that those institutions are worth defending. There’s a way in which the central question of the chapter about the protest is a question that I feel very much in America right now, which is: Where do we look for a unifying story or vision? Where do we look for a story we can tell about ourselves that feels adequate to our history and also enabling of a future?

It’s interesting to think, if our structures of government and our relationship to power and capitalism were different, how would the sex we have be different?

Yeah, one of the things that wasn’t talked about much with What Belongs To You was the intersection of the body and economics. How we inhabit our bodies, how we have sex happens in a context, and that context is ideological and economic and political and historical. Sex in a Soviet-style apartment block in Sofia is not exactly the same phenomenon as sex in an Italian city or sex in a park in Louisville, Kentucky.

But I’m also always trying in fiction, and of course one can only fail, to show how erotic relationship is structured and conditioned by politics and economics but not exhausted by them. I refuse a sense of human life as merely determined by these larger structures. To me, fiction lives in the relationship between those larger structural forces and human agency. That space, which is not exactly a space of freedom but is not a space that is foreclosed or fully determined.

That’s one of the most convincing arguments I’ve heard for why someone should be a writer.

[Laughs.] Well, almost all of our lives and thinking exist in spaces of ambiguity, uncertainty and doubt. And yet in much of our public speech and all of our political discourse we use language in a way that wants to deny all of those things. Art seems to me precisely the tool we have for allowing ourselves the fullness of human thinking.

Amy Gall’s work has appeared in Tin House, Vice, Glamour, Women’s Health, the anthology Mapping Queer Spaces, and elsewhere. Recycle, a book of her collages and text, coauthored with Sarah Gerard, was published by Pacific Press in 2018. She is the recipient of a MacDowell Colony fellowship and earned her MFA in creative writing from the New School. She is currently working on a collection of linked essays about queer bodies, sex and pleasure.

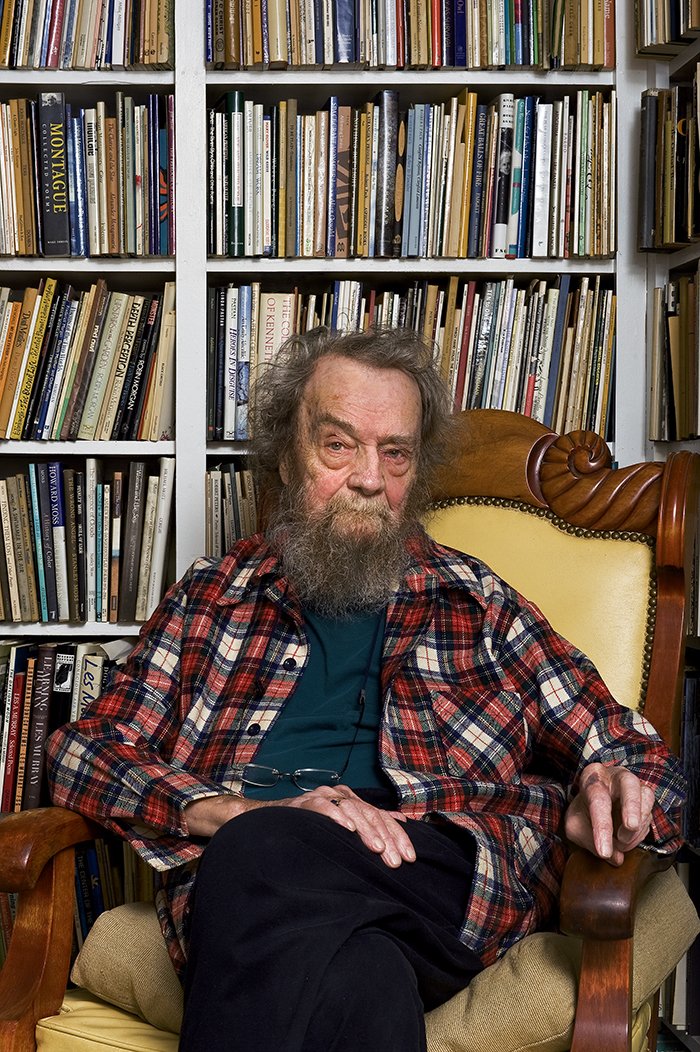

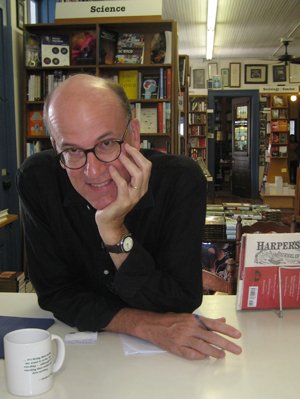

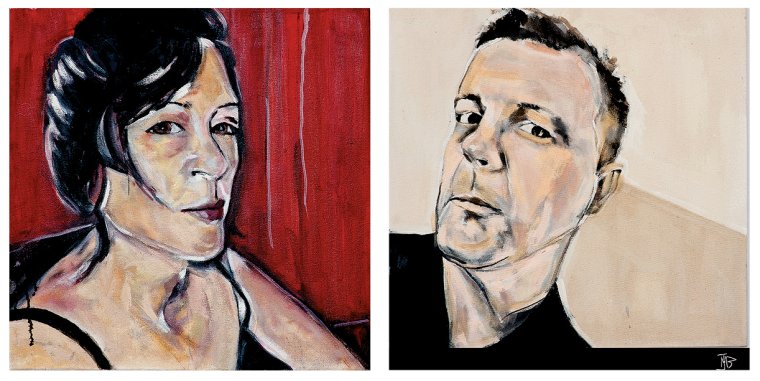

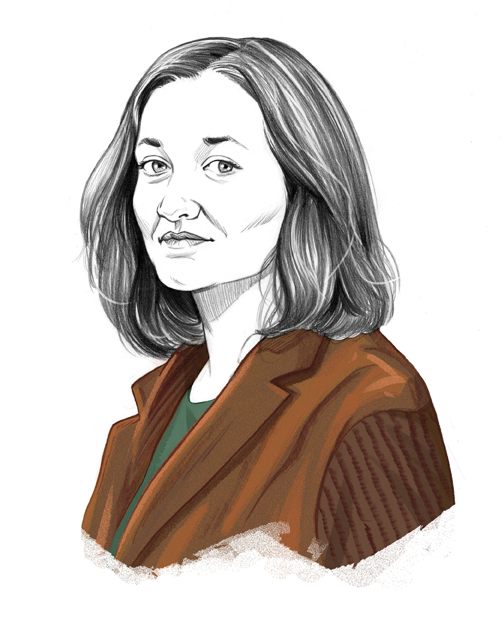

Garth Greenwell, author of Cleanness and What Belongs to You. (Credit: Bill Adams)

Cleanness by Garth Greenwell

Garth Greenwell reads from his novel-in-stories, Cleanness, published in January 2020 by Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Still Dancing: An Interview With Ilya Kaminsky

I first met Ilya Kaminsky more than two decades ago, when we were both undergraduates. Even before the publication of his first very beautiful book, Dancing in Odessa (Tupelo Press, 2004), Ilya’s brilliance was unmistakable. He was different from anyone I had ever met, in the breadth of his knowledge of the poetic canon across time and languages, in the intensity of his commitment to poetry as something more than an art, as a kind of unifying principle of existence. Shortly after Ilya published Dancing in Odessa, he began circulating among his friends a new manuscript, a kind of parable-in-poems about a country whose inhabitants suddenly go deaf, refusing to hear the authorities. Ilya produced version after version of this project, eventually titled Deaf Republic, over more than a decade, while editing anthologies and publishing translations, until it acquired a nearly legendary status among his fellow poets. Graywolf will publish it in early March.

Ilya was born in Odessa, in what was then the Soviet Union, in 1977. Substantially deaf from the age of four, he spoke no English when he immigrated to the United States with his family at sixteen. He studied at the University of Rochester and Georgetown University and has a JD from the University of California, Hastings College of the Law. His honors include a Whiting Award, the American Academy of Arts and Letters Metcalf Award, a Lannan Fellowship, Poetry magazine’s Levinson Prize, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. His anthology of twentieth-century poetry in translation, Ecco Anthology of International Poetry, was published in 2010. He is also the editor in chief of the literary journal Poetry International. After several years teaching in the graduate creative writing program at San Diego State University, Ilya now holds the Bourne Poetry Chair at Georgia Tech. The following exchange was conducted via e-mail this past November and December; it also draws on conversations, many of them on long evening walks, from the month Ilya and I spent together in Marfa, Texas, in late 2016, as Ilya was finishing his manuscript.

What was the genesis of Deaf Republic? How did the idea of a country suddenly going deaf come to you?

I did not have hearing aids until I was sixteen: As a deaf child I experienced my country as a nation without sound. I heard the USSR fall apart with my eyes.

Walking through the city, I watched the people; their ears were open all the time, they had no lids. I was interested in what sounds might be like. The whooshing. The hissing. The whistle. The sound of keys turning in the lock, or water moving through the pipes two floors above us. I could easily notice how the people around me spoke to one another with their eyes without realizing it.

But what if the whole country was deaf like me? So that whenever a policeman’s commands were uttered no one could hear? I liked to imagine that. Silence, that last neighborhood, untouched, as ever, by the wisdom of the government.

Those childhood imaginings feel quite relevant for me in America today. When Trump performs his press conferences, wouldn’t it be brilliant if his words landed on the deaf ears of a whole nation? What if we simply refused to hear the hatred of his pronouncements?

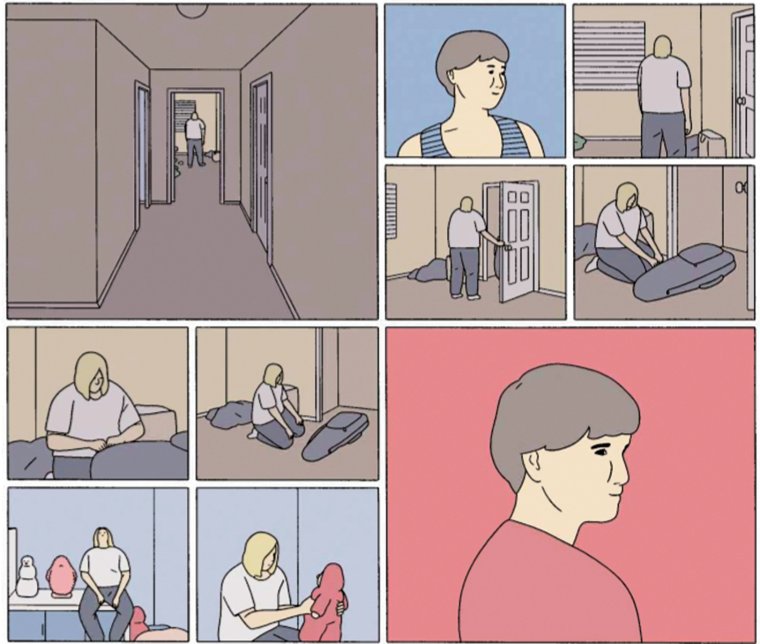

I want the reader to see the deaf not in terms of their medical condition, but as a political minority, which empowers them. Throughout Deaf Republic, the townspeople teach one another sign language (illustrated in the book) as a way to coordinate their revolution while remaining unintelligible to the government.

What led you to write about this invented country at war, and how did you discover your central characters, Sonya, Alfonso, and Momma Galya?

Like many others, I am a misplaced person, a refugee, a man cut in half by history. A part of me is still in Odessa, that ghost limb of a city I left. While these characters are imagined, they are also my family. I keep seeing images related by my grandmother about her arrest by Stalin’s regime in 1937:

When the police come to arrest her, they go straight to the kitchen. Right past her. The first policeman. Second policeman. Third. Straight to the kitchen. To the stove. To smell the stove, to see if she has burned any documents or letters. But the stove is cold. So they walk to her closet. They finger her clothes. They take some for their wives or daughters. “You won’t need any of this,” they tell her. And only then do they shove her into their black car.

They are so busy taking her things that they don’t notice the child in the cradle.

The infant stays in the empty apartment when she is taken to the judge. (The child in the cradle, my father, will be stolen and taken to another city. He will survive.)

She doesn’t know this. She also doesn’t know her husband was shot right away. The judge tells her, “You have to betray your husband in order to save yourself.”

She says, “How can I do that to the father of my child? How will I look into his eyes?”

She doesn’t know he is already dead.

And so she goes to Siberia for over a decade. And behind her, the infant stays.

Though the invented country you write about resembles Eastern Europe, the first and last poems in the book explicitly address our American moment. Do you think of this as a book about America?

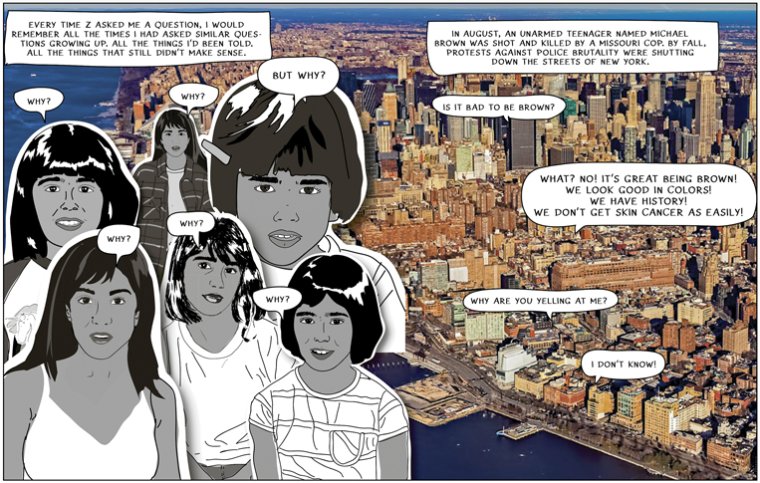

As Americans we want to distance ourselves from a text like this one. But there is pain right here in our neighborhoods: We see stolen elections, voter suppression. Is this happening in a foreign country? No. A young man shot by police in the open street lying for hours on the pavement behind police tape, lying there for many hours: That is a very American image. And we talk about it for a bit on TV and online. And then we move on, like it never happened. And children keep being killed in our streets. This silence is a very American silence.

That image of a shot boy lying in the middle of the street is central to Deaf Republic. Of course, the book is a dream, a fable. But as you note, it begins and ends in the reality of the United States today. That is intentional. It is a warning of what we might become. Of what kind of country we have already become.

Americans seem to keep pretending that history is something that happens elsewhere, a misfortune that befalls other people. But history is lying there in the middle of the street. Showing us who we are.

In all the years of our friendship, I don’t think I’ve ever asked you why you first began writing poems. How did you first discover poetry?

The late 1980s in Odessa was the time when poets worked at newspapers. Many newspapers were faltering. It was a somewhat hungry time. It was the most exciting time. A publisher came to my classroom.

Who would like to write for a newspaper?

A room full of hands.

Who would like to write for free for the newspaper?

One hand goes up.

Which is how I found myself at twelve years of age writing articles for official and unofficial newspapers.

In the hallway at a newspaper I met an old man with a cane, Valentin Moroz, a legendary Odessa Ukrainian–language poet, a man who was often in trouble with the party officials in Soviet days.

He was reading Osip Mandelstam in the hallway, sitting next to me in the hallway, unable to sit still, unable to read quietly, unable to pretend that he isn’t inhaling the large gulps of free air with every line of verse. His voice trembling as he read a stanza, then turning to a young deaf boy: “Do you hear? Do you hear? This is Mandelstam, this son of a bitch, Mandelstam, no one writes better than this son of a bitch Mandelstam. Don’t you know this Mandelstam?”

I didn’t know.

Moroz stood up. He read in the busy hallway standing up. He took me by the hand.

To the tram.

To his apartment.

He recited poems by memory all the way from the hallway to the tram station and all the way on the tram to his place.

I left his place with a bag of books and with a handwritten note not to come back next week unless I had read and memorized poems by Mandelstam.

Thus began my education.

And how did you start writing in English?

When we came to this country, I was sixteen years old. We settled in Rochester, New York. The question of writing poetry in English would have been funny, since none of us spoke English—I myself hardly knew the alphabet. But arriving in Rochester was rather a lucky event—that place was a magical gift; it was like arriving at a writing colony, a Yaddo of sorts. There was nothing to do except for writing poetry. Why English then—why not Russian? My father died in 1994, a year after our arrival to America. I understood right away that it would be impossible for me to write about his death in the Russian language, as one author says of his deceased father somewhere, “Ah, don’t become mere lines of beautiful poetry.” I chose English because no one in my family or friends knew it; no one I spoke to could read what I wrote. I myself did not know the language. It was a parallel reality, an insanely beautiful freedom. It still is.

What changes for you as a poet when you write in a second language?

Even the shape of my face changed when I began to live inside the English language.

But I wouldn’t make a big deal out of writing in a language that is not one’s own. It’s the experience of so many people in the world; those who have left their homes because of wars, environmental disasters, and so on.

What’s important for a poet speaking another language are those little thefts between languages, those strange angles of looking at another literature, “slant” moments in speech, oddities and their music.

Could you say more about those oddities?

The lyric itself is a strangeness inside the language. No great lyric poet ever speaks in the so-called proper language of his or her time. Emily Dickinson didn’t write in “proper” English grammar, but with a slanted music of fragmentary perception. César Vallejo placed three dots in the middle of the line, as if language itself were not enough, as if the poet’s voice needed to leap from one image to another, to make—to use T. S. Eliot’s phrase—a raid on the inarticulate. Our contemporary, M. NourbeSe Philip, has created her very own music out of the language of colonial power. Paul Celan wrote to his wife from Germany, where he briefly visited from his voluntary exile in France: “The language with which I make my poems has nothing to do with one spoken here, or anywhere.”

How important is language or nationality to your identity as a poet? Do you consider yourself a Russian poet? An American one? Is that a meaningful distinction to you?

Well, I still write in Russian from time to time. And I read in Russian a great deal. But do I consider myself an American poet? Yes, I do. But, then, I must answer a question: What does it mean to be an American poet? What is my American experience? It is laughing with my friends, making love to my wife, fighting with my family, loving my family, loving the ocean (I love water), loving to travel on trains, loving this human speech. But we all have these things, don’t we? Yes, we do. And therefore, I fiercely resist being pigeonholed as a “Russian poet” or an “immigrant poet” or even an “American poet.” I am a human being. It is a marvelous thing to be.

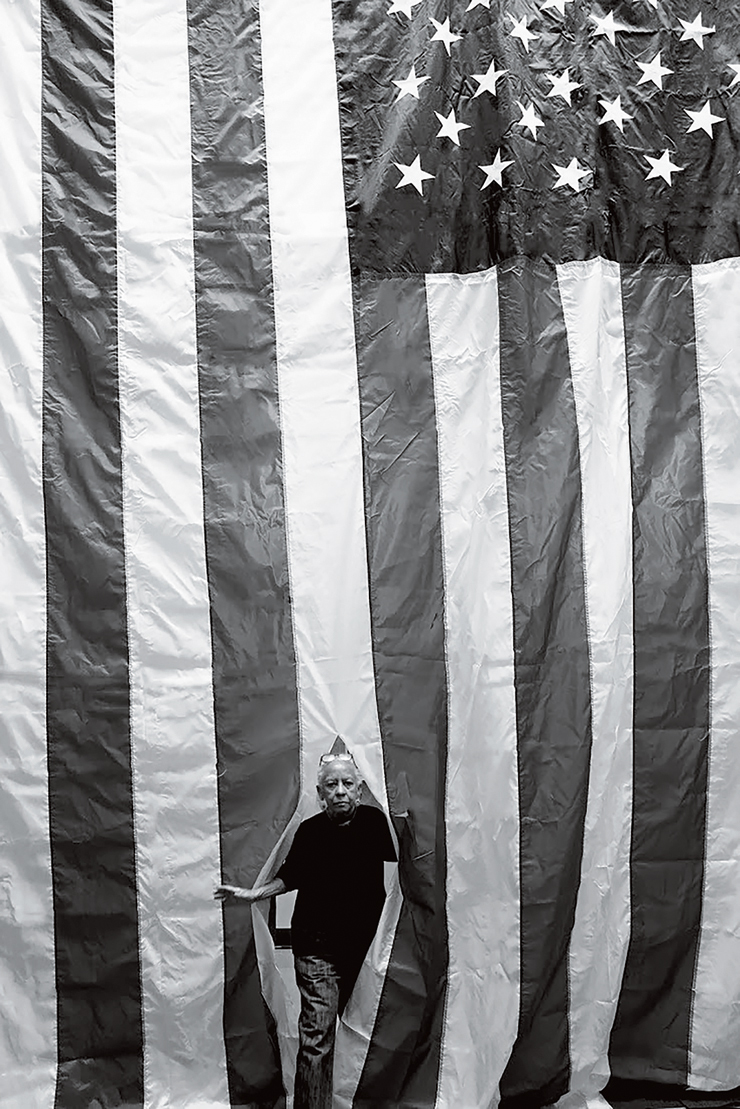

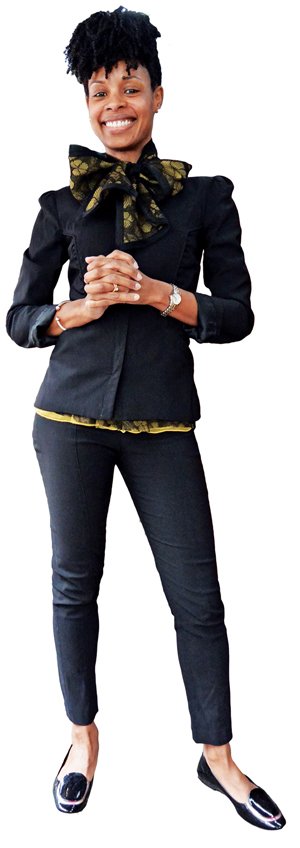

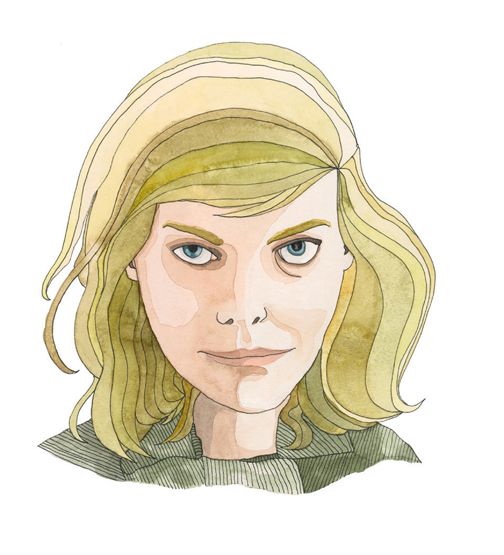

Ilya Kaminsky (Credit: Bob Mahoney)

In these poems you don’t flinch from the terror and carnage of war. But there are also very beautiful, even ecstatic poems of marriage and new fatherhood. What is the role of joy in a poetry of witness? What place is there for beauty and laughter in art that confronts horror?

Yes, many poems in this book have to do with civic strife. But the story circles around the life of two newlyweds, the moments of small joys in a young marriage. It is a book of motherhood and fatherhood; it is a book of private happiness. I am a love poet, or a poet in love with the world. It is just who I am. If the world is falling apart, I have to say the truth. But I don’t stop being in love with that world.

True witness isn’t just about violence and war. To only notice those things is to witness only a part of our existence. But there is also wonder.

I see it as my duty to report this lyricism in the whirl of our griefs. It is a personal responsibility for me: My father was a Jewish child in occupied Odessa who not only suffered, but also learned to dance. He was shaved bald so that Germans wouldn’t notice his dark hair. The Russian woman who hid him, Natalia, hid him for three years. It is not an easy thing, to keep a restless child inside for three years. Natalia taught him how to tango. And so they danced for the three years of that war, in a room where the curtains were always drawn. Once, he escaped outside to play and the German soldiers saw him, so he ran to the market and hid behind boxes of tomatoes. All my friends tell me there are too many tomatoes in my poems. They say there is too much dancing. Is there enough? I don’t know.

Today Ukraine is at war again. I go there about once a year. Donetsk is occupied. In Odessa, that party town, there are terrorist attacks. A café I liked to frequent got blown up hours before I was to meet a friend there. That friend, the poet Boris Khersonsky, gathered neighbors around the ruined entrance to the café and read his poems aloud. Some folks brought food to give away for free.

Even on the most unnerving days there are very tender moments. We have a duty to report them, too.

Here is another image from the early 1990s, from a different war: Transnistria, just sixty-five miles from our apartment in Odessa. I am fifteen years old. People knock on our door saying they fled without a change of underwear, asking to please let them make a phone call. In this chaos people lose their pensions, their homes, but they still go to the city garden in Odessa and dance while old men squeeze their accordions. Old women polka across the street, their medals clinking, beer bottles raised in the air as the rest of us clap from the benches. Time squeezes us like two pleats of an accordion.

Is it foolish to speak of little joys that occur in the middle of tragedy? It is our humanity. Whatever we have left of it. We must not deny it to ourselves.

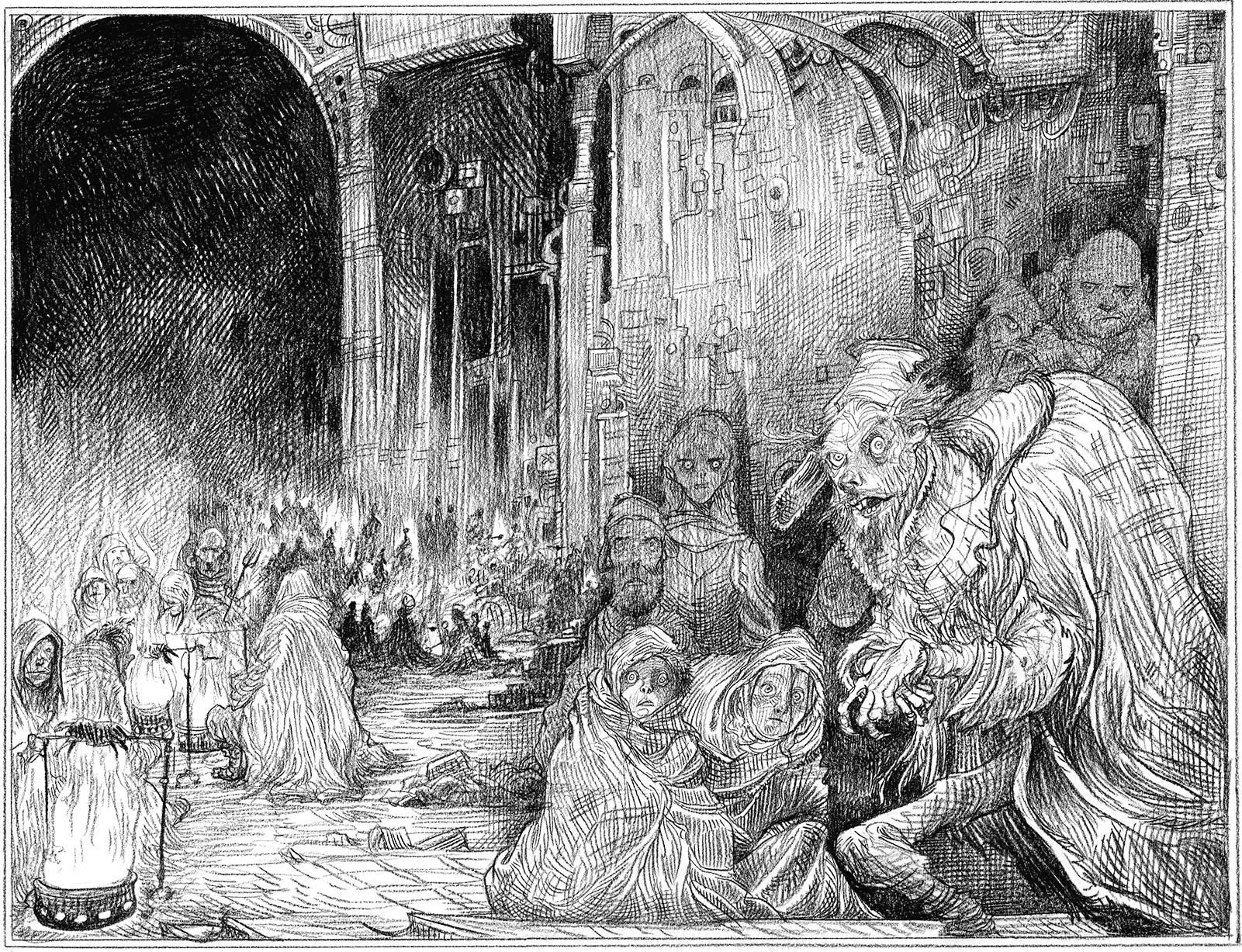

Your story begins when a boy is shot while he’s watching a puppet show. In the second half of the collection, Momma Galya organizes a resistance movement from her position as a director of the local puppet theater. For American readers, can you talk a bit about the importance of puppet theater in Eastern Europe and about why you made puppet shows so central to your book?

The carnival has often been a feature of rebellion. Puppets serve many purposes—on the one hand, especially here in the States, they make people laugh. But they aren’t just comedians; they are often the tools that bring the sharpest criticism to life, making those in power a laughingstock. They are an art of revolt.

At many points in European history puppetry was blamed for inciting revolutions and forbidden. England, Portugal, Germany, and France had laws criminalizing puppeteers at various times. This is not surprising, as the police state is always nervous of places where people gather together.

When the Czech language was banned in the Austro-Hungarian empire, puppeteers continued performing in Czech as an act of defiance. Later, during the Nazi invasion, Hitler closed hundreds of puppet theaters, but the anti-fascist puppet plays of Karel Capek were staged underground.

In England the puppets Punch and Judy were wildly popular, appearing onstage to laugh aloud at the powers that be and breaking every law. They were the heroes of the poor, gathering huge crowds at fairs. The church and government called Punch the corrupter, and, of course—happily—he was.

In America, we have Bread and Puppet Theater, which is one of the best things about Vermont. They believe in the revolutionary role of public art in a time when so much art has been commodified. They had plays in the time of the Vietnam War, after the Kent State shootings, and during both Bushes’ Iraq wars. And you won’t find it in mainstream newspapers, but here in America, riot police fired bean bag rounds at protesters who refused to disperse after watching puppet shows in Eugene, Oregon, in 2000.

Our reality, like that of Deaf Republic, is as fabulist and mythical as it was in medieval Europe. We just refuse to see it.

Russia’s most famous puppet is Petrushka, a Punch-like figure first played by the skomorokhi, traveling players. In Soviet times, the Sergey Obraztsov puppet theater in Moscow, the largest in the world, was wildly popular. And even in Siberia, in the gulag—as my grandmother, who spent over a decade there, told me many times—there were small puppet theaters put on by the prisoners.

She said when men or women from a puppet theater were executed or died of exhaustion, other prisoners hung puppets on their window, or laid their puppet on their empty bed.

Much of your career has involved making a case for the importance of poetry as a tool of political witness and resistance. I also think, from conversations we’ve had, that you believe poetry is the most powerful mode of human communication across gulfs of time. What are your thoughts on how poetry is able to address both its own particular moment and the no-moment of eternity?

Poetry is the art that smashes the borders of time, to misquote Boris Pasternak. For me poetry is a moment of awe—that silence that travels from one human body to another by means of words. Gilgamesh was written four thousand years ago and it transforms us still. Or take our contemporary Gwendolyn Brooks. She died almost twenty years ago but is perhaps more relevant now than ever before; people feel compelled to make a whole new form—the golden shovel—in response to her music.

This is what poetry is: not a kind of public posturing but a private language of music and imagery that is strange and compelling enough that it can speak privately to thousands of people at the same time.

In poetry, borders of nationhood and time collapse: Sappho and Catullus are just as relevant now as Allen Ginsberg and Claudia Rankine.

The poem is a charm; it must actively cast a spell on the reader now. If it doesn’t, it fails, whether the poem is about a face that launched a thousand ships or about a woman standing in a line outside a prison wall or about plums in the icebox. That freshness of speech ravishes the human in us.

I don’t see any value in asking whether poetry can exist outside of the political. Poetry is not about an event. It is the event. Art is the resistance of complacency: It always stands in opposition to numbness.

That is why it just doesn’t die, poetry—despite so many death notices. It is always there, waking us up when we get numb, poking us in the eye.

Garth Greenwell is the author of What Belongs to You (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016). A new book of fiction, Cleanness, is forthcoming from FSG in January 2020.

Ilya Kaminsky (Credit: Bob Mahoney)

Deaf Republic by Ilya Kaminsky

Ilya Kaminsky reads three poems from Deaf Republic, published in March 2019 by Graywolf Press.

Read “Still Dancing: An Interview With Ilya Kaminsky” by Garth Greenwell in the March/April 2019 issue of Poets & Writers Magazine.

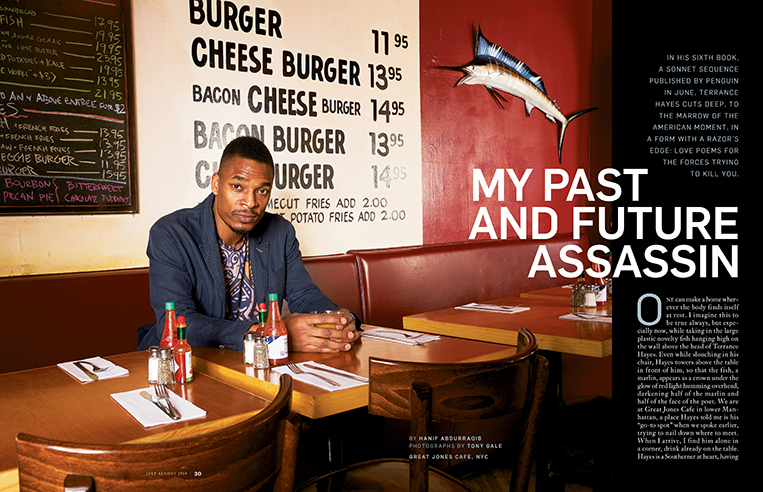

Shape-Shifter: A Profile of Marlon James

Marlon James and I have met before, many times, but never in Los Angeles. A Facebook update this morning informs me that James’s favorite city in America is L.A. I’m waiting for him in the lobby of the Line hotel, Koreatown’s very hip, very industrial, very dope—to quote its enthusiasts—singular travel destination, but I’m worried about the noise. Elevator jazz is playing overhead, and the aqua-blue couches and glass dining tables are packed with folks just like us talking about business deals, and art, and literature, and vastness, and coffee roasters, and Hollywood. When he arrives we sit at the far back of the lobby, away from the bustling entrance. I ask, “Why is Los Angeles your favorite city?” and he says “ha” in the new way we’ve all come to share the sentiment: being reminded that hundreds, sometimes thousands of “friends” and “followers” are reading the minutiae of our daily lives, even if they don’t click Like or leave a comment. The practice is popularly known as lurking. I call it research. “I still think art can happen here,” he says. “New York has museums, but museums aren’t culture. Museums are a graveyard for culture. If I am this year’s Patti Smith, I cannot go to New York, but I can still go to Los Angeles. There’s a sense of possibility here. Kendrick, and Anderson. Paak, the Black Hippy movement, Kamasi Washington, all of that is Los Angeles.” He turns the question on me, and I don’t even need to think about the answer. I love the desert, the mythos of the Western frontier, the apocalypse. “I’m going to die in the desert,” I say, and we both briefly acknowledge the setting sun, pink with hints of orange, bouncing off the backs of buses moving slowly down Wilshire Boulevard, before getting down to business.

I ask him a question about the world since Donald Trump when he lets out another hearty laugh. Hearty laughter and Facebook will become a theme of our two and a half hours together. “That’s usually a question I get from the foreign press,” he says. James doesn’t take a breath between sentences. “The most powerful aspect of fascism is that nobody knows they are sitting in fascism when they’re in it. Trump is disruptive, but he’s not transformative. We’re going to see more literature coming out of this administration than coming out of 9/11. 9/11 was instantaneous. We’re not even sure how to process this yet.” I’m reminded of the tense, private conversations I’ve had with friends since the 2016 election: reviewing our savings, taking on extra work, scaling back, canceling vacations. We’re sure that the worst of the recession is on its way, and none of us are prepared to survive it. Forget talking about the bizarre, carnival-like press conferences; no comment on the sitting president’s outrageous ideas regarding climate change; I don’t bring up the migrant children in detention centers. I’m still anchored to the end of James’s last sentence. He’s right, I can’t even process the daily news. In the name of self-care, unplugging, unwinding, getting over and getting through, I close my app like everyone else.

I’ve sat down with James many times before, so I know his cadence. We’re talking about novelists now, and apathy, and James is about to bring his point full circle. “Every book is political. Not political is politics,” he says. “I’m not on a mission, but I think a writer has to talk about what’s in front of them, even when writing about shape-shifting creatures.”

Marlon James is the author of four highly acclaimed novels. His first, John Crow’s Devil, which was rejected seventy-eight times before it was published by Akashic Books in 2005, went on to be named a finalist for a Los Angeles Times Book Prize and the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize. His follow-up, The Book of Night Women (Riverhead Books, 2009), won the 2010 Dayton Literary Peace Prize and the Minnesota Book Award and was a finalist for the 2010 National Book Critics Circle Award in fiction and an NAACP Image Award. His magnum opus (to date), A Brief History of Seven Killings, won the 2015 Man Booker Prize, the OCM Bocas Prize for Caribbean Literature for fiction, the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for fiction, and the Minnesota Book Award.

His new novel, Black Leopard, Red Wolf, published by Riverhead Books in February, is the first book of an epic fantasy trilogy about Tracker, a hunter known widely for “his nose,” who is tasked with hunting down a mysterious boy who hasn’t been seen in three years. Tracker, who some have called a wolf, finds himself working with a ragtag band of hunters, some human and others supernatural, including a shape-shifting mercenary named Leopard, all searching for the boy. As Tracker and his group move closer to discovering the boy’s location and true identity, they come under attack by enemies near and far. Weighing in at 640 pages, Black Leopard, Red Wolf is in many ways the novel that James was destined to write. While much of the media hype has been focused on the fact that James wrote an epic fantasy, I am intrigued for all of its other riches: This is James’s first book that is not set in his native Jamaica, his first book about empire. I would argue that James has never been more free. Though he read African mythologies and epics for three years before writing one word, Black Leopard, Red Wolf is a testament to his own make-believe. “I really wanted to geek out and write the story I wish I read as a kid,” he says. “I am writing the stories that I want to read about Jamaica. I wrote the stories that I wanted to read about Jamaica.”

Mic drop.

![]()

The Man Booker Prize win catapulted James to international stardom. With the win, he joined the “one-name club,” composed of those writers and artists whose legend has no ceiling and no floor: Jesmyn, Edwidge, Colson, Zadie, Toni, Hilton, Jamaica, Gwendolyn, and now Marlon. With that kind of glory comes fame: Melina Matsoukas, the visionary, two-time Grammy Award–winning director of music videos, films, and television shows (most notably Issa Rae’s Insecure on HBO), is leading the adaptation of A Brief History of Seven Killings for Amazon Studios.

After such a meteoric rise to the heights of literary fame, I am curious about whether his approach to writing this new book was different from the others. “All my books start with trial and error,” he says. “There were four or five versions that I tried. This is the one that worked. I was talking to Melina [Matsoukas]—do you know her?” he stops to ask me. It was my turn for hearty laughter. Of course I know Beyoncé and Solange’s personal director. We have brunch all the time. He returns the laughter. “Well, we were talking about Showtime’s The Affair and the changing perspective. That’s when it occurred to me that Tracker could tell this story, but if you want to believe him, that’s your business.” How perfect, I thought. The Black woman director adapting your most critically acclaimed novel is also talking shop with you about your draft-in-progress. This is some kind of psychedelic, neon-haired P-Funk dream that could only happen in a Black Los Angeles where Black people not only know the future, they are writing and directing it.

Still, James is modest in discussing his success. “I write the kind of books where if people don’t say, ‘Read it,’ people don’t read it. God bless those people who can write best-sellers. I don’t write great white saviors; my books are pretty nihilistic; things don’t end well, and I think something like a Booker Prize got more and more people to read my work. It’s hard for literary authors, for authors writing people of color.” James is standing for his ovation, but he’s also aware that every pair of hands in the auditorium counts.

“Yeah, but what about the bad parts?” I ask. There’s rarely a story this enchanted without a poison apple.

James is only the second Caribbean winner to win the Booker, following Trinidad-born V. S. Naipaul, who won the award in 1971. “It also changed the kinds of scrutiny I get,” James says, “which brings us back to Facebook. Any little thing I say on Facebook ends up in the Guardian and international media, but it hasn’t made me less outspoken.”

James is referring to two particular instances here but offers no further elaboration, and I don’t prompt him to say more. In November 2015 James responded to novelist Claire Vaye Watkins’s five-thousand-word Tin House essay “On Pandering” that would rock the Internet for weeks. In it Watkins discusses motherhood, misogyny, publishing, and pandering, which she refers to as performing for the imaginary white, male audience. “I have been writing to impress old white men,” she wrote. For as much as “On Pandering” does do, there is so much that it doesn’t do: It doesn’t consider the lives and journeys of writers of color, it doesn’t consider that her readers are people of color, and it doesn’t hold white, female publishing gatekeepers accountable for continuing to popularize and publish a very particular type of literature again and again. James wrote on Facebook: “While she [Watkins] recognizes how much she was pandering to the white man, we writers of colour spend way too much time pandering to the white woman. I’ve mentioned this before, how there is such a thing as ‘the critically acclaimed story.’ You see it occasionally in certain highbrow magazines and journals. Astringent, observed, clipped, wallowing in its own middle-style prose and private ennui, porn for certain publications.” The Guardian would go on to say that James “slammed” and “blasted” the publishing world in his retort, but James did what Black people do every day: He pointed at what was standing right in front of him and called it out for exactly what it is.

Fast-forward two years and James would find his Facebook posts in the news again. On June 16, 2017, a jury acquitted officer Jeronimo Yanez in the shooting death of thirty-two-year-old Philando Castile during a traffic stop in Falcon Heights, Minnesota, just north of Saint Paul, where James has lived for more than a decade. Castile, an employee of Saint Paul Public Schools, was shot seven times. Diamond Reynolds, Castile’s girlfriend, live-streamed the immediate aftermath of the shooting on Facebook, and one can see Officer Yanez still pointing his gun at Castile’s dead body. Reynolds’s four-year-old daughter is in the backseat.

The Washington Post picked up the story following James’s Facebook essay-post “Smaller, and Smaller, and Smaller,” written the day after Yanez’s acquittal. Though James is one of the most famous people in Saint Paul and one of the most recognizable, he carries the burden of not appearing “too big” or “too close” (a phrase coined by comedian Dick Gregory in 1971) to white people but especially to police officers. He points out that while some Minnesotans want to “rebrand this state as North,” in reality, North is merely a romanticized concept in race relations. This is where I press James for more. We talk about living in this country, in the world as Black people, as writers, as people who travel frequently and observe everything. I bring up Garnette Cadogan’s groundbreaking essay “Walking While Black” and James nods in recognition. “Garnette’s piece made me think about how I don’t know how to stand still. Talking about Philando Castile, I don’t know if I should stand up and get shot, read my phone and get shot, blink and get shot. I don’t know what actual physical activity I can do, including standing still, that I can do and not get shot.”

“And Tracker?” I ask, thinking of James’s protagonist roving through forests, mountains, and enemy territory with bands of people after him.

It’s obvious that James has thought a lot about his newest protagonist and state-sanctioned surveillance and violence. “It’s important for Tracker and Leopard that shape-shifting is a pleasure, and it’s a nature, a survival, but not in the same way. They’re not being monitored and watched. They don’t have a city system and a state working against them.”

At this point we take a few moments for ourselves to clear the air of the weight of Black death. Thankfully James has one of those urgent texts that happen when you land in L.A., and I need more water.

![]()

When we return to the table, James is laughing. “It’s amazing that people think I am outspoken on Facebook, because I still feel like I have to hold back. I feel if I really, really said what I want to say, I could still be deported,” he says. We are laughing again partly because that is both a half and whole truth, and as Black people we are on the inside of it: It is true that James will always say what needs to be said, and that’s the source of his authority and mastery, and it is also true that James lives with the everyday threat of harassment, deportation, and violence, if someone in power decided to make it so.

“Are you ready to talk about this novel finally?” I ask. Beaming, he claps his hands and pumps his shoulders a few times like a beautiful, broad-shouldered athlete being interviewed after a victory. “Ready!” he says with a smile.

James explains that break dancing, Labelle, Star Wars, and Jamaican fashion magazines of the eighties and nineties were his first experiences of futurism. I want to know what appeals to him about genre, specifically. Any close reader of James’s work will tell you that A Brief History of Seven Killings, which delves into three electrifying decades of Jamaican history around the attempted assassination of Bob Marley, is pretty genre-defying itself. It is clear that James has a fondness for crime and mystery, an admiration threaded through all four of his novels. “Most of the books I read when I was younger were fantasy, comics, crime, and children’s books, and children’s books themselves are usually all of those things. Part of it is growing up in the Caribbean.” Here, James paraphrases Gabriel García Márquez: “Living in the Caribbean is wilder than the wildest fiction.” James credits his grandparents and his favorite aunt for his love of imaginative fiction. “Stories you’re told as a kid are always fantastical. I’m growing up in Jamaica, and I’m in a Jamaican pharmacy, not even a bookstore, you’re not going to find Moby-Dick. You’re going to find a novelization of Star Trek. Even my sci-fi fantasy cinema language is not the movies; it’s the books I read. It’s very dime-store, very pop comics; quite frankly it’s whatever got dumped in the third world, and I gobbled up all of it. I mean, I read Superman III as a book.” He returns to his love of Los Angeles briefly and says, “L.A. is the place where genre fiction exploded with the two genres I like the most: sci-fi/fantasy and crime. The crime novels of L.A. have a wider campus than anywhere else.”

James wants readers to be “exhausted” by the time they finish Black Leopard, Red Wolf from putting the full story together for themselves. “I realized reading all of the African epics, the awesome complexity of these narratives and how much intelligence that they’re expecting from the reader. People are more complicated than simple story; the gods are more complicated than that. They expect you to have the intelligence to navigate the treacherous waters.” And James flings us directly into turbulent, unreliable waters in Black Leopard, Red Wolf. He forces us to second-guess Tracker, Leopard, the entire cast of characters, and ourselves. While most epic fantasies look to the hero-crusade model, James knew from the outset that his trilogy would do none of that. “Respectability politics is Black people playing Anglo. It’s tying to a value system that I have no interest in writing about. I wasn’t interested in writing a sci-fi movie in brown face. Firstly, if you’re interested in African storytelling, realize that the trickster is telling the story, so the whole sense of authenticity and authority that we attach to storytelling—throw that out of the window. I knew I was going to write a hedonistic, queer, selfish character. I’m not interested in inner nobility. That’s a European, Christian narrative from the Crusades.”

And the novel is gay. “Gay gay,” James adds. We’re both reminiscing about our time as baby queers who weren’t yet out. I tell him about my times riding the train from Poughkeepsie to basement parties in Brooklyn where money was collected at the door by a dyke elder, bottles of Heineken were for sale in the kitchen, and we were left alone to grind against each other for hours in the dark. Ladies only. James chimes in, recalling his own closetedness and coming out. “I was in the Bronx with the Jamaicans,” he says, “and I’d take the 5 train to Barnes and Noble, to Union Square. Just to walk around. Just to be out. Our built-in desire to shape-shift is always there.” James scoffs at the notion that an African epic can’t also be queer. “The novel is super fluid and super sexual because Africa is fluid and sexual. Pansexuality, queerness, nonbinary is not new to Africa. White people like to think it is.” Being queer doesn’t mean that someone isn’t problematic, and Black Leopard, Red Wolf’s Tracker isn’t without his problems. He’s a misogynist, but unlike other authors, James takes his character to task. “It was very important to me that Tracker is called out on his sexism. I’m not having that.”

Before our time together comes to an end, I tell James that he can’t get away without talking about process and craft. James is a tenured creative writing and literature professor at Macalester College in Saint Paul. When I ask him how he managed to write another 600-plus-page book, he scoots closer to me and shows me his iPhone screen. He opens his gallery to dozens and dozens of panoramic photos of his office wallpapered in bright index cards and sticky notes, mostly pink, yellow, and green. He shows me maps of various African dynasties and the map of his own new novel that he designed himself. I can see that besides being meticulous and organized, he’s simply happy that someone asked him about craft—for once. Before closing his phone he gives me a final observation on craft: “People disregard plot because they’re not really that interested in their characters.”

We get up to hug and ask the lobby attendant to take our photo together, though we’ll see each other soon: The very next night, on the rooftop of the same hotel, Riverhead Books and Entertainment Weekly will throw a party for him. The Los Angeles Times will be there, Roxane Gay, Carolyn Kellogg, the who’s who of literary L.A.

James will be standing in the center of the room, dashing in a traditional Arabic black thobe with a high slit on one side, his thick hair pulled back, a composed celebrity. There will be two signature cocktails, a large spread, and heaps and heaps of praise for what is sure to be this year’s blockbuster book. Every guest will be greeted at the door by James’s team with the question, “Are you a black leopard or a red wolf?” When I arrive and it is my turn to answer, I scan the room for James and lock eyes, blow him a kiss, before turning to his team and saying, “I am both.”

Kima Jones is a poet and prose writer living in Los Angeles, where she owns and operates Jack Jones Literary Arts, a book publicity company.

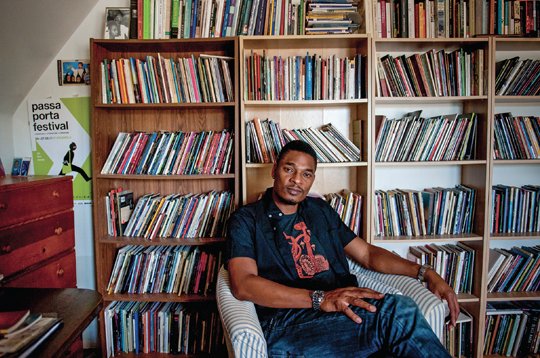

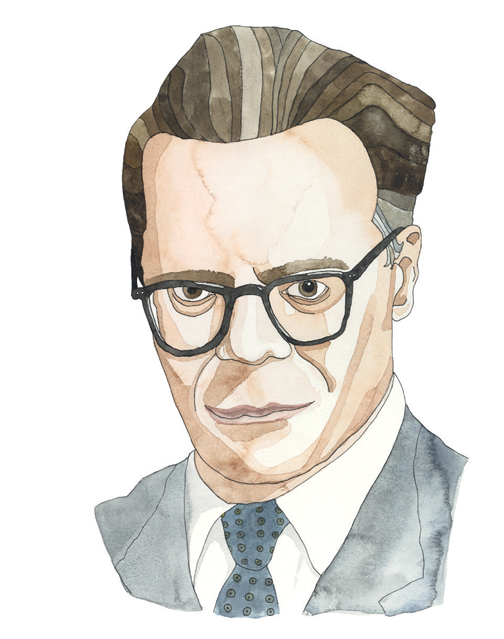

Marlon James.

(Credit: Sara Rubinstein)

Episode 24: Marlon James, Ilya Kaminsky, Valeria Luiselli & More

Twenty-Two of the Most Inspiring Writers Retreats in the Country

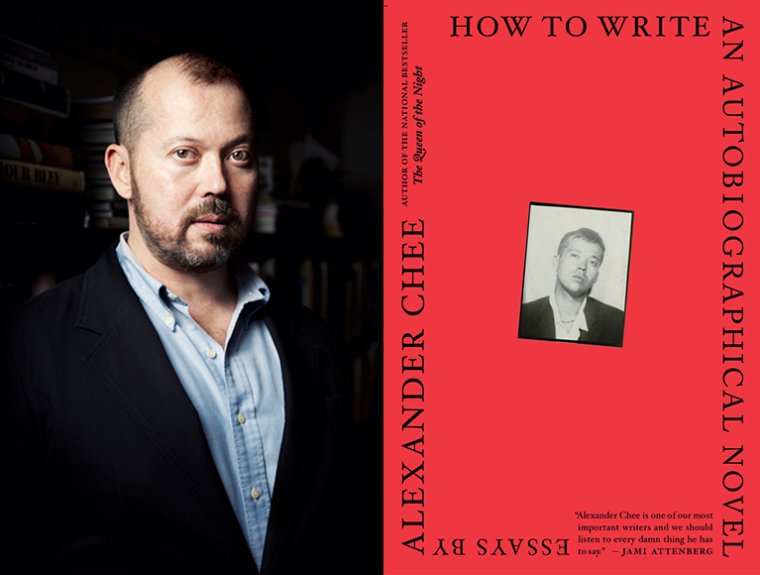

Twenty-two writers, including Alexander Chee and Rebecca Makkai, offer their personal take on the best retreats for productivity, motivation, networking, and more.

Reviewers & Critics: Maureen Corrigan of NPR’s Fresh Air

In this continuing series, a book critic discusses the unique challenges of reviewing for radio and how she picks the books that make it on the air.

March/April 2019