How can you blend ‘work for hire’, ghostwriting, and being an indie author into a successful hybrid career writing books for children? Aubre Andrus gives her tips.

In the intro, Countdown Pages on FindawayVoices by Spotify; the impact of AI narrated audiobooks on Audible [Bloomberg]; Ideas for short fiction anthologies and Kevin J. Anderson’s Kickstarter; Penguin Random House launches internal ChatGPT tool for employees [Publishers Lunch]; 2024 is the year AI at work gets real [Microsoft].

Plus, reasons for the new theme music, licensed from AudioJungle for 10m downloads (the podcast is up to 9.7 million with the old tune); and planning for my Kickstarter launch for Spear of Destiny.

This podcast is sponsored by Kobo Writing Life, which helps authors self-publish and reach readers in global markets through the Kobo eco-system. You can also subscribe to the Kobo Writing Life podcast for interviews with successful indie authors.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

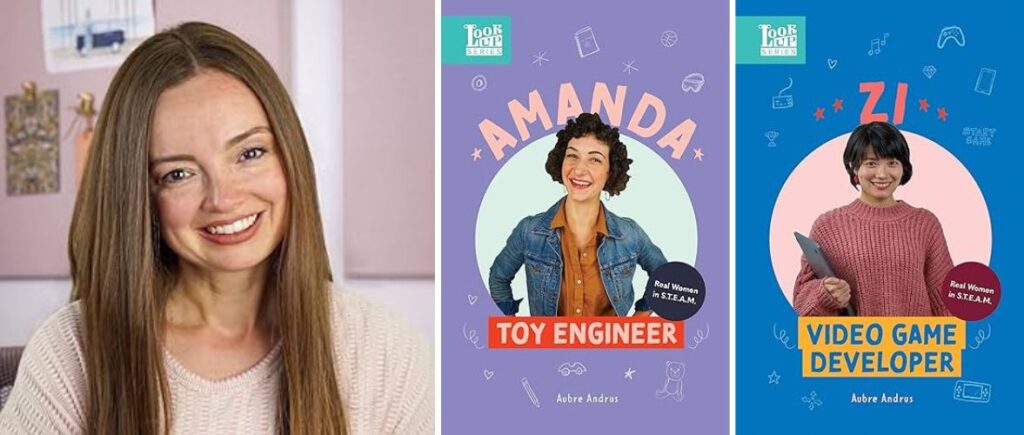

Aubre Andrus is an award-winning children’s author with more than 50 books, as well as being a ghostwriter and former American Girl magazine editor. Her books, The Look Up Series, feature women in STEM careers.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- The background of the American Girl brand

- Pros and cons of work for hire and ghostwriting

- Work for hire best practices to make it worth the money

- Differences in work for hire contracts and payment models

- How to seek out work for hire projects

- Using lessons learned from past projects in your own series

- Creative control over content and marketing a self-published author

- Marketing self-published children’s books

You can find Aubre at AubreAndrus.com.

Transcript of Interview with Aubre Andrus

Joanna: Aubre Andrus is an award-winning children’s author with more than 50 books, as well as being a ghostwriter and former American Girl Magazine editor. Her books, The Look Up Series, center around women in STEM careers. So welcome to the show. Aubre.

Aubre: Thank you so much for having me.

Joanna: I’m excited to talk about this today. So first up—

Tell us a bit more about you, how you got into writing children’s books originally, and how you started out in work for hire.

Aubre: So I started at a kids’ magazine right out of college. If anyone is familiar, the company was American Girl. So they publish magazines, books, and also have an extensive doll collection that’s very popular in the US.

So while I was working at the magazine, I noticed the book department next door and all the wonderful books they were creating that I had also read as a child. I learned that they were developing all of their concepts in house, and then just hiring authors to execute those ideas.

I also learned that a lot of them were former magazine editors. So it was interesting to me that one day, perhaps, I could leave the magazine and then pitch myself to become one of these authors. So that is what I did.

It was interesting because American Girl was based in Middleton, Wisconsin, in the US. That’s very much in the Midwest, not near New York City publishing. So we’re very much an island separate from any other type of children’s publishing, like the industry.

So even though I got my foot in the door in publishing books, I was still kind of stuck. Like, uh oh, is there any way I can expand this anymore? Do other publishers in New York do this also? I had no idea.

I just started networking at children’s book conferences, and frankly, just blindly reaching out to people and saying, “Hey, do you offer any work for hire projects? I’ve done a couple. I’m interested in doing more.” So I was able to slowly build up that work for hire career.

Joanna: I have a few questions about this. So first of all, I have been in of the American Girls stores in New York. So I am aware of this, but I know some listeners won’t be. So can you maybe just talk a bit about that?

I was just fascinated. It did seem to be more modern as in it wasn’t just really old school stuff, there were more modern female role models, I guess. I mean, that’s what the worry is with these older IP brands, is that they have an old, outdated version of what women are.

Talk about how these IP brands work, and if people don’t even know what American Girl is.

Aubre: So it started as kind of like an heirloom doll company from a former teacher and textbook author. So she was really like an educational entrepreneur. So she was sort of not interested in Barbie for her nieces, and she was trying to create something better, in her mind’s eye.

So she developed this line of three dolls that were historical characters that then also had a series of six books that accompanied them. It basically was teaching girls what it was like to be a girl back in time.

You know, so what was it like to grow up during World War Two? What was like to grow up as an immigrant coming to the US for the first time? Then it kind of expanded from there, the historical doll collection.

Then it really ballooned into just creating contemporary content for girls. That’s what I was a part of at the magazine, which was just like a lifestyle magazine for 8- to 12-year-old girls.

Similar to at the time there was Nickelodeon Magazine, Disney Magazine, Highlights Magazine, like in that same vein, but specifically targeted about girlhood and for girls in that 8 to 12 age range.

Then from there spun the contemporary line of books, and a lot of like crafts, and activity, and recipe, and slumber parties, and just anything that kind of celebrates that girlhood from ages 8 to 12. Then the dolls also then became more contemporary, a line of dolls that looked like you.

Joanna: Like customized content.

Aubre: Yes, and that’s really where the company stands today. The historical characters, I think maybe girls today aren’t as interested in them, but there is the line of dolls that look like you and you can dress.

They have partnerships with Harry Potter and anything you can imagine, so it’s quite a fun company. I loved it as a kid, so it was amazing for me to work there as a grown up.

Joanna: I mean, as business people, we have to think this way. I feel like so often because we are, and the listeners, we’re authors first, we’re books first, and I think we forget that there’s so many other things.

Brands like American Girl, they’re good examples. Even if no one is interested in that particular type of thing, the business model is great. I mean, obviously, Barbie does it so well as, as well. So I do like this idea of thinking further than just a book, even if, of course, we’re not going to grow a whole empire like this.

You mentioned it was separate from New York publishing. Did you almost feel like sort of second rate? I don’t want to use that word, but you know what I mean. Did you find that difficult?

Aubre: I did. I mean, we were so isolated from New York publishing. I think, you know, this isn’t an offense to anyone who’s working there, I think they would all agree. Some of them have gone on to work for more like New York City publishers, and it is more fast paced, and it’s just different.

We sort of had our own little bubble and had our lovely little pace, and we were creating amazing stuff for kids. So I felt like I knew American Girl publishing, but I did not necessarily know children’s book publishing. So it was a little intimidating to dive into that.

Joanna: Yes, and on that, I mean, you mentioned networking and going to conferences. I still remember how it felt as a newly self-published author, to feel kind of second rate, to feel looked down upon, to feel like I was a second-class citizen. I imagine you kind of felt that way when you were networking and at conferences.

How did you get through that mindset in order to meet people at these conferences?

Aubre: Well, I mean, I felt that way, that second rate way, in so many ways, because A, I had only done publishing in Middleton, Wisconsin, and then B, I was doing middle grade, which at the time was not hot, not sexy. Everyone was doing YA.

Then I was also doing nonfiction, which also is not fiction, which is where most people want to be. Then also, I was doing work for hires, I wasn’t even developing the concepts myself. So there were so many reasons why I felt like a second-rate author. Like, am I a real author? I don’t know. So for a while there, I really second guessed myself. Then I just kind of had to get over it like that.

I started working with really amazing brands, like National Geographic Kids and Disney. I mean, these are amazing, and people would kill to have these opportunities. So I just really started embracing work for hire. I get to work on so many fun projects for really amazing brands and IP, and that’s really cool. So, yes, I just had to kind of mindset shift.

Joanna: You gave yourself like a talking to and said, make the most of it.

Aubre: Yes.

Joanna: I do think it has to be a mindset shift if people feel that way. Like you mentioned, whether it’s the type of publishing you do or whether it’s the type of genre you’re writing.

What’s so funny, I think, with the self-publishing world, is that the romance writers in old school publishing were always looked down upon. People who wrote romance were considered sort of lesser in some way. Now, it’s very clear, and it always has been true I think, but before it wasn’t so known that they make so much money and they prop up basically the rest of the industry.

Aubre: Exactly. I mean, it blows my mind if anyone ever looks down upon romance. It is the industry, and they are so savvy. I actually keep quite an eye on the romance industry because they are just so smart and what they’re doing works. So even though I’m writing books for kids, I’m always kind of peeking over there. Like, wow, they’re creating these universes, they’re doing this on TikTok. I’m always so impressed by the romance community.

Joanna: They are always ahead. Well done, romance writers listening. I always wish I could do it, but I can’t.

Aubre: I’m thinking about it. I’m always like, hmm could I do that? I’m starting to read more in that genre because it is interesting.

Joanna: That’s interesting. Okay, so let’s come back to the work for hire because, of course, you mentioned some of the great brands you’ve been writing with. So I guess one thing is that that is an amazing experience.

What are some of the pros and cons of work for hire and ghostwriting?

Aubre: Well, for me, it was a great way to dip my toes into the water, instead of just jumping into the deep end, and slowly build up my skills as an author. I imagine some people who hit it big on their first novel, I mean probably are just absolutely drowning in the industry and don’t feel very savvy.

I’ve really been able to build up a knowledge of different publishers, of different types of projects, discover what I’m good at, what I like. I’ve really just got a wide range of experience that has only made me a better author.

So after I left American Girl, I took a job in marketing, but I was freelance writing on the side. So compared to freelance writing—because then my dream was to eventually go freelance and just to be a freelance writer—I would have had to take on so many freelance writing projects that pay like two hundred bucks.

I mean, I still see some of these come across my social media feeds. So if they’re paying $200 for an article, I mean, how many articles would you have to write and pitch to make a living?

So compared to freelance writing, this is fewer higher paying projects. I like that so much more. I get to control the workload. I can even take on some freelance projects outside of this field. In the past, I’ve dabbled in content marketing and social media to kind of balance my day.

I don’t need to come up with the ideas, I just need to execute someone else’s ideas. So it’s a little bit, you know, I have felt that I was on a hamster wheel of content production, for sure, absolutely.

There is a hustle element to it of always trying to find the next gig, but I have to remind myself that I’m in control of my workload.

I can turn down a project, if it doesn’t pay well, I can hold out for the higher paying project.

I do get a lot of the benefits of a traditional process. I get royalties, I’ve gone on book tours, I have fan mail, I do school visits, I’ve done book events. So really, I’ve gotten everything I wanted out of being a children’s book author from these work for hire projects. Also, I see that most books don’t earn out their advances.

So there is a balance to it, where I’m like, am I on a hamster wheel? Can I ever get over this hump? But at the same time, I feel like we’re all kind of on a hamster wheel. Unless you really hit it big on one huge book project, like you’re always going to have to keep pumping out books in a series or—

Joanna: Marketing the backlist.

Aubre: Exactly. I mean, marketing is exhausting as well. So in general, I’ve very much had a good experience with work for hire. I get my name on the cover and on the spine, depending on the project. I think it just really depends on the publishers you’re working for and the relationships you establish. Then from there, you can put your own ideas, you know.

Then the cons would be like, maybe you’re working on some projects that you’re not as excited about. You can always say no, but you know, when you’re getting your foot in the door, you might take on a few things that aren’t exactly in your wheelhouse.

I always saw these projects as stepping stones to where I wanted to go, whether it was a stepping stone to get into a certain publisher, or just establish myself with an editor, or kind of wade into new waters.

I kind of slowly stepped into narrative nonfiction and eventually started doing narrative nonfiction novels. Now I’m doing a lot of short story fiction, and I hope that leads to a fiction novel. So there’s these ways to slowly build up your skills through work for hire.

Joanna: Yes, I mean, I think some people will be like, yes, but you said they’re not your ideas. You’re basically writing someone else’s ideas, and that, to me, seems one of the biggest issues. So I have co-written a few fiction projects and nonfiction. The fiction, I found extremely hard because I don’t play well with others. I was like, I do not want to write anything that is not what I feel is me. So how do you get over that?

I mean, tell us how the process works. If you take one of these projects on, do you get given story beats? Is there anything you can do that’s individual or—

Do you just flesh out what someone else has written as an outline?

Aubre: Well, I can speak to my experience in the nonfiction children’s book world, and that is often I’m just given like a title. So I really can run with it. You know, I get a lot of control and a lot of the responsibilities put on me to flesh out a project.

I have also done ghostwriting for fiction, so I think it just depends on the project. I agree with you that fiction is much harder. I have a place where I want the story to go, and it might not be the place where what we would call the author—which is the person who came up with the idea, you would be the ghostwriter—where they want it to go.

So you’ve got to look at it more like, this is my client, and I am trying to make my client happy. On those type of projects, I don’t want my name on them. I want my name on the paycheck, I don’t want my name on the book.

I think that’s how I get over it. I’m just like, this is not mine. I am helping them do theirs, this is their thing, and that is what it is.

In the kids’ nonfiction, I’ve had a ton of fun and a ton of agency to do what I want with the project. They’re looking for my expertise to really bring this to life.

Joanna: So the other thing I’ve learned about people, like yourself, is you have to be incredibly professional, and you have to work to deadline, and you have to do a whole load of things that, frankly, some authors can’t do. So tell us about the level of professionalism and your best practices.

How do you get these projects done in a timely manner that make it worth the money?

Aubre: Yes, so most of the projects have pretty quick deadlines, like the writing portion is really just going to be like three months. So I’m a fast writer, my background is in journalism.

So at this point in my career, I just know what I need to do to get this project done. Get your butt in the chair, get the outline, just start writing. I might start at the middle of the book, the beginning of the book, the end of the book, whatever is like hitting me in that moment so that I can get it done.

If some idea is flowing, I’m going to run with it. I’m not going to necessarily write the book from beginning to end because, again, I’m doing a lot of nonfiction. So that has helped me make these projects worth it. Also, maybe not like over researching, because I know, especially with a journalism background, I could easily fall into that rabbit hole.

For the most part, I’ve had very few projects where I’m like, ugh, that was not worth my time. Those were mostly like kids’ craft and science experiment books. Those just take more time because you have to test the crafts, test the science experiments, maybe something didn’t work and you have to scrap that whole page or that chapter, do it again. So again, I’ve just kind of learned that if I’m going to take on a project like that it has to pay quite high.

If I’m going to take on an early reader for National Geographic or something, those are really fun and quick to write and they pay well. So there’s such a wide range in the kids’ publishing world.

I have friends who do a lot of work for hire fiction, and they are just excellent at it. They love developing story and just pumping it out, like that’s their favorite part of the process. They’re just going through the process and can just do it as fast as they can. I’m not super fast with fiction, which is why I haven’t taken as many fiction projects. I do really well with short stories where I have some constraints, but not the idea of a whole fiction project that is work for hire.

I think, for me, it’s good because you are given some characters and a loose outline and an idea. So it’s more almost like a writing prompt. You know, like I’m almost getting paid to execute a writing prompt.

So it kind of just depends on if that’s something that sounds exciting to you or not. Like, for me, I work good under deadlines, I work good when I have a little prompt and a format. You’re often given a title and the page count.

Usually it’s part of a series because this is work for hire. So I wrote something for American Girl, it was A Smart Girl’s Guide: Travel, and they have a whole Smart Girl’s Guide series.

Joanna: So you get a style guide?

Aubre: Yes, like I know what these other books look like, I know kind of how they’re divided up. I’ve read a lot of them. I’m just familiar with it, so it just comes faster.

Joanna: I’ve met quite a lot of writers who have written in the Star Wars universe, or The X Files. All of these franchises, they do have the book of the TV show or the film. You know, Doctor Who, or that kind of thing. So I feel like this is quite common. It’s funny, it’s kind of common, but not talked about that much.

Aubre: Well, exactly, which is why I wanted to talk about it.

Joanna: It’s so interesting. You said earlier that you do get royalties. Now, I thought this was one of the biggest issues, certainly with some of the worlds and universes that people have written in, is that they do not get royalties. Often work for hire is—whatever’s in the contract, obviously—but usually it’s: you write it, we pay you once, and you never see any other money. That is kind of the freelance model.

Does that just differ by contract?

I mean, even if you do get royalties, it must only be a small percentage.

Aubre: Yes, it just depends on the contract and depends on the publisher. So I’ve gotten them for multiple publishers. Then also some publishers decide, well, if we came up with the idea in-house and you executed, then it’s a flat fee. If you come up with an idea and we run with it, then we’ll give you royalties. So I’ve had that happen too.

So it just depends on the project, and the publisher, and the budget, and also on negotiating. Most people don’t use an agent for work for hire projects because the pay is less. So it’s not really financially worth an agent to go seek out these projects.

So when you establish these connections and relationships, you can learn a bit more depending on the publisher. There’s certainly a lot of work for hire opportunities that pay royalties.

I mean, I just see like Disney Publishing coming out with a lot of different fiction series and working with big name authors. I have to assume that those are paying royalties. So there’s all different levels of work for hire projects.

Joanna: Okay, so you said there’s loads of work out there. So how would people get into it if they wanted to? Like I sometimes say to people, well, you can write a book for them, and one for you. You can use it as almost day job type money while you’re building up your own stuff.

How would people get that kind of work?

Aubre: So I think particularly in the kids’ book industry, it would be beneficial if you had some experience writing for kids.

Whether that be magazines, or your own stuff that you’ve created, or even if you have a teaching background, you’ve developed curriculum, or you’ve created programming and libraries. School teachers and librarians often become children’s book authors.

Then I do a lot of networking at, as I said, children’s book conferences. So very occasionally there’ll be a panel about work for hire, but even if there’s not, anytime you meet an editor you can just ask them. “Do you do any work for hire projects? Does your publishing house do any work for a prior projects?” You know, “Do you know an editor who does any work for hire projects?”

You can find a lot of this on LinkedIn too if you search for editors at various publishing houses. Not everybody fills out their LinkedIn, but if you are looking for keywords like “works with freelancers,” “hires freelancers,” like “develops concepts in house,” and then “finds writers to execute them.”

If you look, a lot of these editors work in the licensing division because this is who’s in charge of the intellectual property and franchise and those types of projects.

There’s so many TV shows, and if you’ve walked around a bookstore, you’ve seen this.

So many TV shows, movies, brands who then want to create a publishing program around that IP.

They reach out to a publisher, and the publisher acts as a consultant and helps them develop this program.

Usually, that means they’re developing the concept in house, and then they’re hiring a writer to execute it. So basically, LinkedIn and conferences is where I’ve done a lot of my networking. Then I have—I’m a little bit extra—so I have like flown to New York and set up meetings and gone out of my way to really get my face in front of some editors.

Joanna: Then I guess once you’ve done one or two things, then you know the right people.

Aubre: Yes, then it’s much easier to spin those projects into further work.

Joanna: I just want to come back on another of the negative things here. So there’s been some court cases around this type of stuff, so if you’re writing in someone else’s world, even if the contract is that you come up with your own ideas. Let’s say you come up with a new character, but you write it into an American Girl world, you no longer have control of that character. That’s usually the way it works.

If you’ve written it into their world, then they own it.

Aubre: Right. I feel like even in the traditional model of publishing, you’re giving up the copyright as well. So I don’t see it as too different than that way. Even if you pitched your project to a traditional publisher, and they signed you, they would own the copyright to that project, you know.

Joanna: Only if that’s what the contract was, how long you assign the copyright to a publisher. Only if they ask for life of term of copyright, do they have it for term of copyright.

I think this is really important in terms of mixing IP. So it might be tempting. Like, I know people who get co-writing deals with bigger names, and then they kind of feel like they want to write a character from their series into someone else’s world.

You just have to be so careful with this commingled IP because you don’t know. I mean, the thing is that so many authors think, oh, well, my stuff isn’t that valuable, and that other person’s stuff is more valuable. That may not be where it is in like 20 years though.

Aubre: Right. I’ve never experienced that. Any fictional character writing that I’ve done has been in a pretty strict universe, like Disney Princess, you know, where there’s very strict brand guidelines. I wouldn’t even be allowed to necessarily create a new character. It would really be existing characters within the universe. So I haven’t really confronted that.

Joanna: Okay. So it’s interesting because, of course, you’ve done a lot, and you still do a lot of this writing in other universities, but you also have your own series, The Look Up Series.

Tell us more about that and why you’re so passionate about STEAM.

I thought it was “STEM” and you used both, I think. Explain that if people don’t know.

Aubre: So STEAM and STEM. STEM is science, technology, engineering, and math. The A in STEAM is for art. So STEM has sort of naturally progressed into STEAM because, and as I’ve met many women in STEM and interviewed them, you really can’t do a lot of these more scientific and technical fields without a creative mindset.

As a kid, I was always creative and thought that meant I’m an author, I’m an illustrator, that’s where I am. I’m not a scientist, I’m not good at math. It turns out that these more scientific and technical fields actually require you to be super creative when it comes to problem solving or anything. So I have a series called The Look Up Series, and it features real women in STEM. It’s targeted for 8- to 12-year-olds, it’s like a middle grade nonfiction series.

Each book features a really awesome career, really amazing woman, and sort of what she was like as a kid, what this career is like, how do you get into this career.

So for example, I have Dr. Maya, Ice Cream Scientist. So she’s a real woman who is an ice cream scientist. So it’s interesting to see how she has her PhD in food science, but she’s also being very creative using flavor, and visuals, and ice cream.

It’s this cool mix of science, and arts, and just helping kids get excited about really cool careers in science and technology and engineering, and also learning that just because they have maybe been pegged as creative or artsy, doesn’t mean that they can’t also land in these more scientific and technical fields.

These jobs are really in high demand, you know, as the next generation enters the workforce. We need people to be solving the world’s biggest problems, which is often in these STEM fields. There’s obviously a huge wage gap and gender gap when it comes to these careers, which is why I’m featuring women. I have diverse women on the cover, just so every kid can see themselves in these roles.

Joanna: What did you bring to your series, in terms of the lessons learned from all these other IP worlds you’ve worked in?

Aubre: So it was very important to me to, one, create a series. So I’d always been interested in self-publishing. I’d always been traditionally published, I’ve written more than 50 books for kids for like major publishers.

For many reasons, like we mentioned the content hamster wheel, we mentioned royalties, IP, all that, and I wanted to create my own thing and have more income potential. I also just wanted to write on a project that was purely me that I was super passionate about.

I certainly could have pitched this to a publisher, and I think I could have got some bites, but I really wanted to do it myself. It was a nice test of all of my publishing knowledge. So it was important to me to create a series, so there was more potential in marketing it and making an income. Then I really just got to learn everything.

I would say it’s been both easier and harder than I thought. Easier, in that like none of the systems, or the technology, or the gatekeepers behind ads, or awards, or reviews, or whatever are complicated. Like you can definitely figure it out as an indie author.

What was harder for me was like the mindset and the investment, like you really have to cut out to be an entrepreneur. That means spending money on ads and maybe not turning a profit right away. That was really hard, and still is hard for me.

It’s an investment, but it brings me back to the books I’ve written where, you know, a lot of my books are only marketed for couple of weeks. So the benefit is that I can continue to market this series, and it won’t get pulled off the shelf. I can recover it, I can retitle it, I can kind of do whatever I need to do with this series.

Also, as we mentioned with American Girl, thinking beyond the book. I can create a web series, or I see a lot of indie children’s book authors creating plushies or like little stuffed animals to accompany their books. So there’s just like more potential because I chose to do this project on my own.

Then I was pregnant with my second daughter as I was creating the series. I was like birthing five books while also preparing to birth a child. So I created this whole series while I was pregnant with her. It was just like I felt more of a legacy to leave for them. I felt like it was a passion project, and it just felt good to do this project. So that was why I wanted to do it on my own.

Joanna: Yes.

A lot of it comes down to control when traditionally published authors go indie.

Most people say it’s creative control, that’s the main reason, because you don’t have that. Once you’ve written something, even if you’ve got a lot of freedom in writing some of these things before, you weren’t in control of anything else. You can’t fix it later or change the cover, and like you said, there’s no point in marketing those projects.

Aubre: Yes, if I’m not getting royalties on a book, what’s my incentive to market it, and many books have been taken off the shelf.

So it just felt, as I said, just really good to be in creative control, know that my efforts are going to continue to help this series be a success, and also know that it was just aligned with my beliefs. It was just a project I was truly passionate about. It was funny how it kind of came to be because I was actually pulling onto the Disney campus for a project, I was meeting with my editor, and I passed the Disney Imagineering building.

I used to, when I was a kid, I wanted to be an Imagineer. They’re like the engineers and artists that designed the theme park rides, and I had just completely forgot about it. I was like, oh my god, in another life, I would have been going into that building instead of this building. Like, you know, what was missing that I didn’t become an Imagineer? So every project informs another project, I guess.

Joanna: Absolutely. Well, it’s interesting, I mean, you did mention that you’re an illustrator.

Did you illustrate these?

Aubre: Well, I wouldn’t call myself an illustrator, but I was always very into art. So on these books, because my background is at American Girl and we were very until girl aesthetic, I decided to make little doodles on the cover.

So the covers have my doodles, which are not great because they’re supposed to look like girl doodles. So I have made doodles for American Girl Magazine and some books, but I am not a formal illustrator.

Joanna: So you didn’t hire someone separately to do that?

Aubre: I didn’t. The books are nonfiction, so each book is sort of a combination of a biography and activity book. So I relied on the women I interviewed to provide a lot of photos from their childhood. Then combined with these doodles of mine, we were able to piece this project together without an illustrator, because frankly, it would have been quite expensive. I was funding this project myself and launching with five books from the jump.

So maybe one day, I’ll be able to invest in an illustrator and add that to this project. I know my covers feature real women on them, like we did a little photoshoot. So that makes the series stand out a little bit, in a good way or bad way, in that it’s a biography for kids, but it features a non-illustrated cover because these are real women. So it was just kind of a creative decision that I decided to give a try.

Joanna: Yes, because there is a series for girls that has real people, but a sort of cartoon version of them, isn’t there? Like sort of Maya Angelou and people like that.

Aubre: Yes, most of them are illustrated. Even if they feature real people, the covers are illustrated.

Joanna: That’s interesting. It’s interesting that you have based this on, and you’ve got photos from, real people.

You must have had some proper contracts done to work with those people and use their image and their photos in your books.

Like that must have been a bit of a process.

Aubre: Yes, I did work with a lawyer to draft up some contracts. Also, I didn’t want them to think I was like owning their story. Like they can go on and write more books about themselves if they would like.

I basically did the two-plus hour interview with each woman and then translated that into a biography, like a first-person biography. Then I combined it with knowledge of what the field is like, and you know, what this particular career is like.

There were also just questions like: What is college? What is a major? What is a PhD? Then I created some activities at the end so kids can feel like they are an ice cream scientist. We also have Amanda, Toy Engineer, and Angella, Beauty Chemist, and Tracey, Theme Park Designer. So I didn’t get to become an Imagineer, but I did get to interview one. So I got part of what I wanted as a kid.

Joanna: That’s very cool. I guess that contract with those women—

They understand that they’re not getting royalties from the books.

Aubre: Correct. I did compensate them for their time, which is unheard of in a journalistic sense, but I felt that was important. I was really relying on their knowledge, and I think the women I work with are really passionate about getting other girls into STEM. So it was a passion project for them as well. They were very happy to be a part of it.

Joanna: I think all of that is so important. So if people are wanting to work with real people, in whatever situation, there should be communication of what everything is and contractual terms.

The point of a contract is it doesn’t need to be confrontational in any way, it’s more a case of just making sure everything’s right for copyright and all of that.

In the self-publishing space, I get questions from people because people are bootstrapping, they’re doing it themselves. But in these cases, it is very important to get all of those permissions and stuff up front.

Aubre: Yes, that’s one of the reasons I didn’t have an illustrator because of the legal fees.

Joanna: Yes, I get you. Although if people do use an illustrator, for example, then they also need a contract to make sure the copyright is assigned, and all of that kind of thing. So publishing is a business, like it’s a proper business.

Aubre: It is. Absolutely.

Joanna: You’ve learned that as well. So I do want to ask you about the marketing, because of course, when you’re doing work for hire, the marketing is not really your job, but when you’re self-publishing, it is your job.

How are you doing marketing for your own series?

Aubre: So I feel like I kind of have two customers. It’s the kids’ book world, so it’s different. So I’ve got parents, but then I also have teachers and librarians.

So I’m on Amazon, I did KDP, I did print on demand to start with. Then I’ve also done a print run and have a direct-to-consumer site, thelookupseries.com, so I can offer discounts to teachers and librarians and discounts on bulk orders.

I went to the American Library Association Conference, and it was very clear to me very quickly that they don’t have large budgets. You know, they are really tight in these schools and libraries. So it was important to me to be able to offer something off of Amazon where I could offer like a bulk discount.

Then I’ve got the Amazon business, relying on Amazon ads. I do a little bit of Facebook marketing where I’m offering a free activity download, kind of targeting Girl Scout troop leaders or teachers or anyone who has like a STEM space, like a makerspace in a library.

I’ve pulled a little activity from Amanda, Toy Engineer and from Tracey, Theme Park Designer, to capture email addresses and build up my email list. I have done the LA Times Festival of Books and some other children’s book specific conferences.

My next step is I want to go to more STEM-focused conferences. I live in Los Angeles, and there are a lot of like STEM events for kids. Free one-day events where you can get a booth, and I think that would be a great place for me to be.

So I need to remind myself to step out of the children’s publishing world a little bit. I’m very much like, oh, I’m going to go to the library conference and go to LA Times Festival of Books.

It’s like, oh, there are other marketing opportunities besides book people. Like there are STEM people and people who are looking for science content for their kids. So I’m trying to be better about marketing on a more broader sense to those people as well.

Joanna: I think that’s such a great idea, because let’s face it, the children’s book conferences are full of traditional publishers, but also all the other books are there. Whereas if you if you’ve got a booth, and then you’re next to some science thing and some genetics thing, you’re the only one with books, and that makes you stand out.

So I think that’s so good for anyone who writes anything that has a theme, some kind of theme. It doesn’t have to be nonfiction, I think you could still do it with fiction, as long as the theme aligns with that.

Aubre: Absolutely.

Joanna: Do you do any live events?

Going into schools or anything like that? Or is that just not scalable enough?

Aubre: I do. I’m looking at building that up more. COVID really took a hit on that. So I had a little momentum, and then it got squashed. Now I’m trying to maybe pick that up again. Now that I have done my own print run, and I can offer bulk discounts and that kind of thing, I feel better about investing some time into that.

So I have done some school visits, in particular, that are more like going into the auditorium for multiple grade levels, something a little bit bigger than just visiting one classroom. I do offer like a free 15-minute virtual visit on my website, just for individual classrooms. I just kind of see that as a volunteer thing I can offer. That’s kind of where I’m at right now with that.

I do think it’s important that you’ve done your own print run and are able to offer your books at a discount. If you’re buying your author copies from Amazon, from KDP, like I don’t know if the financials will start to work out for you.

Joanna: Oh, no, completely. A lot of kids’ authors use Ingram Spark, and then the schools can order direct.

Aubre: Yes, so I do have that as well. I just have a little bit more of a royalty from my separate print run.

Joanna: Absolutely. Well, then how do you see your future?

How are you going to balance the work for hire with building your own brand and your own book series?

Aubre: I mean, I definitely focused solely on The Look Up Series for like six months as I was launching them, before I had my second daughter. Then coming back, I really hit the ground running on marketing those books, even more after my maternity leave.

Now I’m doing both, I’m balancing work for hire projects with The Look Up Series. It’s actually really nice because with work for hire, like I mentioned, it can feel like you’re on a treadmill and hustling your next gig. Now I feel like I can kind of calm down a bit and wait for the next good gig that I actually want.

I know I’m not wasting my time because I’m in the between because I’m working on The Look Up Series. I’m bringing in an income and building up my business for this more financially lucrative potential.

I’m not just like wasting my time waiting around for a project, and maybe taking a project that doesn’t pay well or that I don’t want to do. I just feel like I’m actually working on something that can last with The Look Up Series.

Joanna: Fantastic.

Where can people find you and your books online?

Aubre: So I’m at AubreAndrus.com. You can check out The Look Up Series at TheLookUpSeries.com.

If you want to learn a little bit more about work for hire, you can go to AubreAndrus.com/WFH. If you’re interested, in particular, in like how to break into the children’s book industry, you can learn a bit more about my background in that.

Joanna: Fantastic. Well, thanks so much for your time, Aubre. That was great.

Aubre: Thank you for having me. It was so nice to bring this to light. I know so many people who it’s their life dream to become a children’s book author. So that’s why I like sharing this like secret backdoor, this other part of the industry that people don’t really talk about.

It’s just another skill in your toolkit, like as an author and a writer. If you ever have a goal to write for a TV show or something one day, writing in these IP, and these characters, and for these brands is just always like a really good skill to have.

Joanna: Yes. Well, thanks so much for your time.

Aubre: Thank you.

The post How Writing Work For Hire Books Led To Becoming An Indie Author With Aubre Andrus first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Welcome back to our journey through the Enneagram types for writers. Last week, we talked about how the complexities of the Enneagram provide valuable insights that can enhance self-awareness and empower your writing journey. The distinctive traits and varying gifts that define different writers’ approaches to the craft create a profound impact on the world of storytelling.

Welcome back to our journey through the Enneagram types for writers. Last week, we talked about how the complexities of the Enneagram provide valuable insights that can enhance self-awareness and empower your writing journey. The distinctive traits and varying gifts that define different writers’ approaches to the craft create a profound impact on the world of storytelling.

Recent Comments