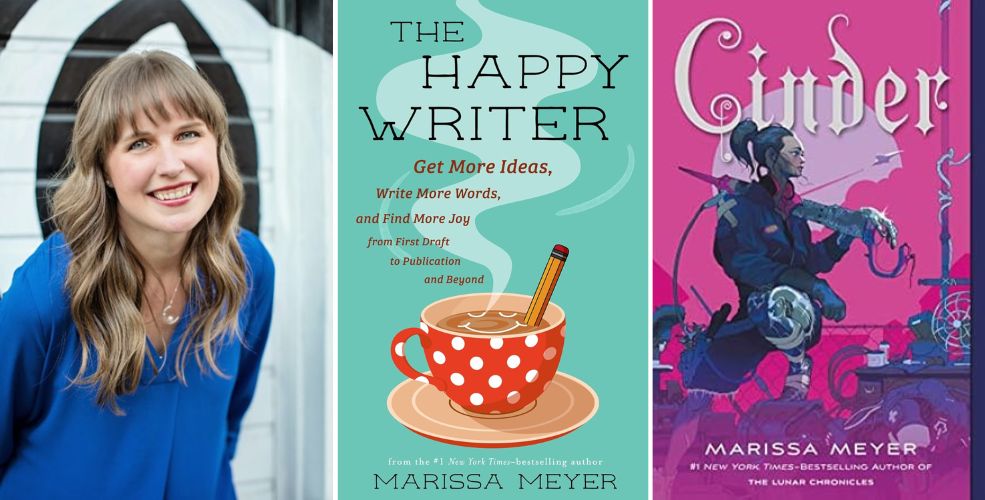

The Happy Writer With Marissa Meyer

How do you keep the happiness and joy in your writing practice, along with managing the business side of being an author? Marissa Meyer gives her tips.

In the intro, How authors can price their books for profit [Self-Publishing with ALLi]; How to recover from author burnout [Self-Publishing Advice]; my Brooke and Daniel crime series in KU; Day of the Vikings; Outback Days and City Nights in the Lucky Country – Books and Travel; replanning with Calendarpedia.

Today’s show is sponsored by Draft2Digital, self-publishing with support, where you can get free formatting, free distribution to multiple stores, and a host of other benefits. Just go to www.draft2digital.com to get started.

This show is also supported by my Patrons. Join my Community at Patreon.com/thecreativepenn

Marissa Meyer is the New York Times bestselling author of fantasy romance and graphic novels, including The Lunar Chronicles. The Happy Writer: Get More Ideas, Write More Words, and Find More Joy from First Draft to Publication and Beyond is her latest book for authors.

You can listen above or on your favorite podcast app or read the notes and links below. Here are the highlights and the full transcript is below.

Show Notes

- Finding joy and happiness in your creative process

- Tips for finishing a first draft when you hit a wall

- Ways to fill your creative well

- How to make your research methods more fun

- Coming up for new ideas within a series

- Managing your to-do list and learning when to say no

- Remaining positive when querying and pitching

- Finding joy in book marketing

You can find Marissa at MarissaMeyer.com or on Instagram @MarissaMeyerAuthor.

Transcript of Interview with Marissa Meyer

Joanna: Marissa Meyer is the New York Times bestselling author of fantasy romance and graphic novels, including The Lunar Chronicles. The Happy Writer: Get More Ideas, Write More Words, and Find More Joy from First Draft to Publication and Beyond is her latest book for authors. So welcome to the show, Marissa.

Marissa: Hi. Thank you so much for having me.

Joanna: It’s great to have you on. So first up—

Tell us a bit more about you and how you got into writing and publishing.

Marissa: Oh, goodness. I always wanted to be a writer. I am one of those. I was a huge reader growing up, loved stories, had a big imagination. So, really, from the time that I was a little kid, I started making up stories and telling them to my parents, asking them to write them down into little books for me.

Then as I got older, I, of course, started writing them myself. Then —

At some point I realized that this is a job. This is something that people actually can get paid for.

You could actually get paid to come up with stories and get your name printed on a book.

I think I realized really early on that that was for me, and that’s what I wanted to do with my life. So I kept writing.

As a teenager, I got really into fan fiction and credit that a lot with learning how to tell a complete story. Beginning, middle, end. I got my bachelor’s degree in creative writing and a master’s degree in publishing because I thought writing might be a difficult career to break into.

I wanted to have a backup plan, and thought, well, if this writing thing doesn’t pan out, maybe I can be an editor, maybe I can be a publicist or an agent or something.

The deeper I got into learning about publishing, the more it really just cemented how passionate I was about writing and how much I just really wanted to be the writer in this publishing equation.

So I wrote many multiple manuscripts that went nowhere, but eventually got the idea for a Cinderella retelling about a cyborg, a futuristic retelling. So that became my debut novel, Cinder.

Joanna: Wow. Okay, so it’s really interesting that you did publishing as a degree, as well as writing.

Did you have a job before you became a full-time author?

Like did you work in the publishing industry? Or did you just go straight from uni into full-time writer?

Marissa: No, I did. From university, I got a job as an editor at a very small publishing house in Seattle. That publisher focused mostly on fine art books. So those beautiful coffee table books that you get at museum exhibits and art galleries. You know those books.

So it had virtually nothing to do with my ultimate career of being a fiction writer, but it taught me a lot about just the behind the scenes, what goes into creating a book, and the actual production of it, the marketing of it, all of these various aspects.

So I did that for five years, and then I spent about a year as a freelance typesetter and proofreader. At which point my first novel sold, and I got to become a full-time writer.

Joanna: That’s very cool. I love that you did typesetting and stuff like that. We’ll come back to the business side, but let’s get into the book.

So you use the words “happy” and “joy” in the book title, but I feel like many writers think suffering and pain is more of a hallmark of the creative process.

If writers are not feeling the ‘joy’ and the ‘happy’ right now, what are some tips for getting back to that?

Marissa: Thank you so much for asking this question. It is so funny to me that we do have this stereotype of the writer. That you must be struggling in order to create art, and you must be suffering some way. If it’s not painful, then how can you possibly call it quality?

This stereotype really bugs me, and I’m really trying to dismantle it with this book. But that said, we’re also not shying away from the fact that writing, it’s not just fun and play all the time. There are struggles, there are challenges, no matter where you are on your journey.

Whether you’re suffering from writer’s block or burnout, whether you’re in the query trenches and you’re facing rejection or criticism. There’s a million things, of course, that can be roadblocks in our path to being happier writers.

That is largely what this book is about, trying to refocus our attention, not on all the things that can go wrong, not on all of the struggles that we face, but looking at the things that we really do love and enjoy about the craft of writing. The hobby, the career.

We get into it because we do have a passion. It’s not the sort of job or hobby that most of us take on just for the heck of it. I mean —

You start writing because you love to write.

So I really encourage writers to find what it is that appeals to them about this. Do you love the process of taking a messy, complicated plot and fitting it together like a big jigsaw puzzle and that satisfying feeling when everything comes together?

Or do you love that you have the freedom to go to a cafe with your laptop and sip lattes all day and stare out at the people and let the world inspire you? Or maybe you love the research process and learning about things that you are so curious and interested in and just want to do deep dives into it.

There’s a lot of things that we can find joy and satisfaction in. So that’s going to be different for every writer, and that’s going to be different based on where you are, both in the process of writing a particular book, but also where you are in your overall career.

I always encourage writers to go back to that. What can I find joy in today?

Joanna: I love the research. I also love saying with a finished book, “I made this.” I always enjoy holding that book in my hand. You, coming from this fine art books thing you did early on, I guess you must love the really beautiful special editions and all that as well.

Marissa: Oh, I love it, and the smell! I love the smell of a new book. You don’t always get it when a lot of books these days just come in like a cardboard box, but some of these special editions will come wrapped in plastic, and so they still maintain the smell of the ink and the binding glue. Ah, I just nerd out over it.

Joanna: Well, and that is important too, isn’t it? I feel like we’ve come around to that. Like there was a lot of focus on digital for a while, especially for independent authors, but now it’s really come round to beautiful, physical products.

That, to me, is a very exciting part of the process, finishing the whole thing with something beautiful. That satisfaction is really part of it.

Marissa: Absolutely. I’m really big on celebrations.

I think it’s so important to take a moment and say, “I made this thing. I accomplished this. I had a goal. I had a dream, and I kept moving. It took months or years or decades, but I did it.”

That is such a huge part of the process.

It’s really easy—and especially like for me, I’m about 20 books now into my career— it can be easy to be like, “Oh, just another one. Set it on the shelf, and keep on working on the next deadline.” I really have tried to be very conscientious about it.

No, let’s pause. Let’s pop some champagne. Let’s take a night off. Let’s get a massage. Like, what is it that’s going to make me feel like, yes, I’ve done it again, and I’m really proud of this moment.

Joanna: That’s great. Well, you do have a section on the writing process in the book. Of course, every author is different, but if people haven’t got to that 20 books place—

Tell us how you get that first draft done. Any tips for actually finishing a book?

Which I know some people have an issue with.

Marissa: Finishing is hard. I think it’s important for people to know that everyone struggles with finishing. We talk a lot about the siren song of the next project because at some point in every book you’re going to reach that point where you’re in the murky middle and it feels endless.

You’re confused about the plot, you’re frustrated that things aren’t going well, and suddenly you get a sparkly new idea for the next thing.

It’s so easy to think, “Ah! That one’s going to be really easy and really fun, and it’s not going have any of these other problems that I’m dealing with right now.”

It’s very tempting to switch over and to follow that path of least resistance. I think it’s important to know that that fantasy of the next one being so easy, probably not reality. Probably you will get to relatively the same point in the process and, once again, be hit with, “Ah, this is hard. It’s work. What else can I do?”

For me, one of the tips that I started using fairly early in my career is when I am at the start of a project, and I’m really excited, and I’ve got lots of ideas, and you can feel all the potential for it, and there’s a reason that you’re choosing to write this thing out of all your other ideas. Why am I focusing my time on this one?

I will write down either a list, or I will write a little letter to myself detailing all of the things about this project that I cannot wait for.

Maybe it’s the romance that I’m really excited to write, or I just love the protagonist, or there’s a really big twist in the plot that I can’t wait to see how readers are going to react to.

Whatever it is, I will write down everything that I really love about this idea. Then when I’m a third of the way or halfway through the book and suddenly hating it and feeling like this is the worst thing I’ve ever written, and I can’t believe that I chose this, what was I thinking, I’ll go back and I’ll read that list.

I will remind myself why I chose this one in the beginning, and what do I love about it? What do I still love about it? Then I will take those ideas and I will try to incorporate them into the next scene or chapter, or couple of chapters that I’m going to write.

“All right, I love the romance.” Well, let’s have a romantic scene. “I think the villain is so cool.” Well, let’s have a scene where we really get to see how cool the villain is. You know, whatever it is, focus on that, and that will hopefully help you get over that bad period.

Joanna: Do you write out of order if you get to that point?

You’re like, I’m just going to write the climax scene because I know that will be fun, or do you write linearly?

Marissa: It really depends on the project. I have done both, and I think both processes work. Some books are more difficult than others.

The books that I’m struggling with more, then I will tend to jump around and go ahead to write a scene that I’m really excited about, but not always.

Some books have very complicated plots that are very interwoven, and in those cases, it can be less of a mental gymnastics challenge if you do write it linearly. So it really depends.

I think, for me —

Momentum and forward progress and consistency. Whatever you need to do to keep moving forward and keep on top of your goals —

whether it’s a word count goal or a chapter goal or whatever it is, anything you can do any day to keep moving forward is going to be helpful.

Joanna: Sometimes that moving forward might not be getting new words down. You also have a section about filling the creative well. Sometimes, especially when you’ve written as many books as we both have, it can be like, okay, do you know what I need? Some more input.

What are some ways that you fill your creative well?

Marissa: Absolutely, and that’s such an important thing to note. Like you say, sometimes getting words down is not the answer.

If you’re facing some amount of creative burnout, or if you’re just really stuck in a plot and feel like things just aren’t working, or maybe you’ve taken a wrong turn somewhere and you’re not really sure how to fix it, sometimes the best thing you can do is take a step back, and do it intentionally.

I think there’s a distinction between saying, “I have writer’s block and I can’t possibly write anything today,” versus, “I am choosing not to write today because I recognize that I need a moment and need some space to refill the well and tap into that creative spark again.”

So, for me, when I decide I’m going to take a day off, there’s a myriad of things that I might choose to do with that time. I think getting outside, going for walks, or if you can go to a park or go on a hike somewhere, if you can go swimming. Anything like that tends to, for me, really generate some new ideas.

Spending time with my family is always good. A lot of times I will use those days off to tackle other projects, things that have kind of been looming in the background. Maybe they’re taking up more mental space than they should be.

That could be things like getting your car washed, or that could be like reorganizing your pantry, just things that have been really bugging you lately.

Maybe it’s time to take a day and clear some of those things out because that will help clear your mental clutter as well.

Or you might take a day and be like, I’m going to do some really fun research about this project. Or I’m going to take a day and spend some time brainstorming or reoutlining my plot.

So you can also take a more hands on approach to writing. There’s really no right or wrong here. Whatever you feel like you need, give it a shot and see if it helps break something loose.

Joanna: You mentioned fun research there. What does that look like for you?

Marissa: All of it. I really enjoy research. I love reading. I love doing deep dives, you know, going on Wikipedia and clicking the little further reading links at the bottom and seeing the rabbit holes you go down.

Also, if I can find a way to do a hands-on or more of an experiential research, that’s the best. Of course, we all fantasize about being able to travel. If you can go to the place where your setting is inspired by, that is worth gold.

It’s not always an option, of course, for different reasons, but if you can get out and see the world and take in these really great sensory details, it is so helpful.

It could also be talking to an expert on something about your story, something about your protagonist or your plot, because they’re going to have just the best insights. They’re going to clue you into things that you never would have even known to look up to research.

I’ve crawled under cars to see how they work because I don’t know anything about cars, but I had a mechanic character, so I better learn something about cars.

I love cooking. If there’s a dish that my character has to cook or bake or is served, I’ll find a recipe and give it a try myself. Just little things like that to just kind of give you that hands on experience. I think it adds a lot to the authenticity as you’re writing.

Joanna: It also makes it more of a fun process.

Marissa: It’s more fun. Why not? We’re all about trying to make it more fun.

Joanna: Yes, exactly. Well, then coming to writing series, because it feels like, obviously we need tropes in the books. If we’re writing different books in a series, we need to make sure the characters are consistent and all that.

How do you keep coming up with new ideas for series?

I feel like a lot of people now are sort of like, okay, is it the same thing, the same thing? What stays the same in a series book and what changes? How do you get ideas for that?

Marissa: That’s a good question, and it’s going to depend on if your series follows one main protagonist versus if it’s more like a loosely connected series with maybe different protagonists or different love interests in each book. Generally, I think it’s more common that you’ve got the solo protagonist who has a complete character arc.

So when I’m thinking of the entire series as a whole and trying to step back and see kind of a big picture, I will give a lot of thought to the protagonist’s arc. Where do they start page one, book one? And where am I hoping they’re going to end up?

Within that, depending on how many books you have in your series, there’s probably going to be some reversals. There might be that in book one, your protagonist might end on a really high note.

Book two, it might be the opposite. They may be way down at the bottom now. Something terrible has happened that they have to claw their way out of.

Or they learn something about themselves in book one, but then book two, you flip it on its head and say, “They thought this thing, but surprise, actually, it’s a negative in some way.”

Playing around with these different moments as the character is changing, developing, learning about secrets, exploring their world.

Generally speaking, we tend to think of character arcs as being upward, but I think it’s helpful to think of it more as a roller coaster. There should be dips, there should be lots of places where things are going wrong.

So that’s one thing that I’m thinking about as I’m putting together a series. Then I’m also thinking about my antagonist and my conflicts. I have often likened it to like old video games, where every level ends with a boss, but then the very end of the game has the big boss that you’re really trying to defeat.

So the first boss, you have barely enough skills to defeat that first boss, and maybe it takes a few tries to beat that first level, but you do it. Oh, but now you have to do the second level, and that next boss is going to be even harder.

As you go, you’re getting better. Your characters are picking up new skills, new weapons, new allies. So at the end of every book we have a conflict, a climax, something that we have to face, and everyone is going to be a step up, a little more difficult than the last one.

So that we know by the time our character is finally ready to face that big conflict, the big struggle, the antagonist, villain, whatever it is you have at the end of the series, that you have given them the skills that they need to actually defeat them.

Joanna: There’s some great advice there. So let’s come into more of the business side because you do have this section on the to-do list. I love this because the to-do list is never ending. For indie authors, we’re publishing, as well as marketing and writing and everything.

How do authors say no and reduce that to-do list, in order to stop being so overwhelmed?

Marissa: Oh, my gosh. It is hard, and I will admit this is something that I personally have really struggled with. I’m a yes person. I like to say yes. I like to please people. I like to feel like I am doing everything within my power to make a book a success, to further my career. So I get it.

I absolutely get how difficult it is to recognize when we need a little space, or we need some downtime, or when we need to take a step back. For me, and I didn’t come up with this, I read it in some productivity guide, self help guide, a long time ago, but it really resonated with me.

Every time you say yes to something, you are also saying no to something.

For example, if you say, yes, I will be on this panel at this book festival.

Okay, let’s say you have to travel there. Let’s say it’s a full day being on the panel. There’s probably going to be a signing. Maybe there’s an author dinner. Another full day of travel going back home. So we’ve got essentially two to three days for that yes.

There’s lots of times when, great, I can’t wait. I’m looking forward to this. I’m going to meet some readers, I’m going to network with authors.

Maybe you recognize that by saying yes to that, I’m saying no to three days with my family, or I’m saying no to three days of working on my novel, or I’m saying no to a day where I could relax and spend a day reading a book and refilling my well.

So none of these are the right option, none of them are the wrong option, but just recognizing that there are pros and cons, and give and take, and be really picky about what you’re spending your time on and what you are making your priority at any given point.

Joanna: It is interesting. You mentioned a panel there, and I feel like conferences and conventions are one of these things that is quite difficult. Now, you and I, again, have been doing this a while, so we have a community, like we have author friends.

There are people listening who might be introverts. They might feel very uncomfortable about going to writing conferences, and they’re like, should I just say no to that? I guess that the question is—

When should you go to something, even if you feel you want to say no?

When do you have to push yourself as an author, and when should you give into those feelings? I know it’s tough, but when have you done this as an early writer and then later stage?

Marissa: This is one of those things where I really think people have to tap into their own psyche and recognize, what are my limitations, what are my goals? For me, early in my career, I did it all. If I was invited to something, it was an automatic yes.

I also did not have children at the start of my career, so for me, when it really started to change, as far as recognizing my time is limited, my energy is limited, I have to step back and say no to more things, was when I had kids.

Then it really became that balancing act of, when do you focus on the writing and the career? When do you focus on family?

That said, I mean, the publishing process, the writing process, there’s ups and downs. There are times when you are really focused on selling a book, on marketing a book, promoting. That’s both with in-person events, doing book signings, doing the festivals. There’s also social media, sending out newsletters.

There’s going to be periods where you’re trying to get your book noticed by readers, but that doesn’t have to be all day, all the time, for years and years and years.

You can really focus on it for one, two, three months, whatever your capacity is, and then step back. Maybe take a hiatus on social media.

Maybe say, for these next five months, I need to write a new book, and I need to focus on being with my family and do some self-care. So for these five months, I’m saying no to all other requests. I mean, whatever it is. I’m just throwing out numbers. Of course, this is going to be different for everybody.

So really think about —

What are my limitations? Know that you really can’t do it all.

I hate saying that because I am one of those people where I feel like I can do it all, just let me try. But you really can’t.

You have to make choices sometimes and recognize that if you’re trying to do it all for too long, then that’s a recipe for burnout. That’s the last thing we want.

The last thing we want is to get to a point in our career where we dread the writing, or we dread the travel, or we dread the book events.

So whenever you start to feel like it’s too much, listen to that and give yourself some space. Realize that the world is not going to fall apart if you take a little bit of time off.

Joanna: I love that. Actually, I prefer this sort of campaign focus, which is what you were really saying there. It’s like, go hard for, say, three months, and then take a couple of months off. I do that. I kind of step back from social media.

Some people feel like they have to do, I know the TikTok authors in particular, are doing a lot of videos every single day. They feel like if they stop, it’s all going to end.

The race never stops, does it? It never stops unless you stop.

Marissa: It’s true. There’s always going to be the next goal post. There’s always going to be that next thing that you’re thinking, “Oh, if I just get this many followers, then I can slow down.”

Then you get that many followers, and you think, “Oh, but I’ve got a book coming out in two months, so I’ll keep going until then, and then I’ll slow down.” “Oh, but now I’ve got this other thing.” I mean, it’s always going to push back. It’s always going to be something else.

It’s hard to recognize when you do need some personal space, but it’s also really important. Not just for our mental health and wellbeing, but for our creativity too.

Joanna: Okay, so another thing that some people are not that happy or joyful about is pitching publishers and agents. Mostly people are quite stressed about that.

Now, you work with traditional publishers. I’m primarily an independent author. There are pros and cons.

Tell us a bit more about your experience with traditional publishing.

Any tips for people who want to position themselves in a world of publishing flux, as ever?

Marissa: Definitely one of the most stressful periods in a career is the pitching to the agents, the querying trenches, the submission trenches. It can do some damage on your confidence, on your everything. So it’s a really difficult period.

If your goal is to be traditionally published, as opposed to independently published, and as you say, great options. There’s so many great directions that we have available to us today.

If you really think you want to be traditionally published, of course, number one, just make sure you’ve written the best book that you can. Get some feedback. Have some critique partners go over it.

Edit and polish it to within an inch of its life.

Then when you feel like, okay, I’ve done the best I can do, write your query letter. Again, get feedback there, because query letters are particularly tricky, and there is a science and an art to them. Do your research.

Then send it off, and, number one, celebrate because it’s so huge. It’s such a huge accomplishment to get to the point where you’re querying. So regardless of whether you get 10 agents interested and it goes to auction at publishers, or if no one bites, like regardless, you have written a complete book and submitted it.

That’s so awesome, so like take a moment to congratulate yourselves and go out for pizza or whatever, whatever you do to celebrate. Then start writing the next thing.

The worst thing that we can do is have this book sent out, and then just spend all day, every day, worried about it and stressing about it and having that anxiety building up and checking our email 100 times a day, which like you’re probably going to do anyway.

If you can, try to refocus your energy on something new, what is the next project you can be excited about?

Then dive into it, body and soul and spirit, and try to immerse yourself in a new story.

This is for a number of reasons. One, because it’s going to be a great distraction. But two, when and if your book on submission gets picked up, your agent is going to ask you, what else you got? So it’s great to have something else that you can talk about.

Joanna: Then what I do like in your book—I mean, I like lots of things—but you do also —

Talk about what might happen if you break up with an agent, or lose an agent or an editor or a publicist.

I like that you covered this because so many people think, “Oh, if I get an agent or a publisher, that’s it forever. My whole life is amazing, and I’m rich and famous, and everything will work out.”

So why might some of these things happen over a career, and what’s the kind of attitude you need to survive it all?

Marissa: This was one of the big surprises for me, as I started to expand my group, my network of writers, how common it is to break up with an agent or to switch publishers, publishing houses, to switch editors. It happens all the time.

This was shocking to me because I very much felt like, no, when you’ve got an agent and a publisher, you are set forever. That is your career, those are your people. So I was really surprised that that is not the case.

There’s so many reasons why one of these relationships may not work out. I’ve had friends whose agents have retired, whose editors have moved to different publishers. So it might be something rather innocuous. Life just happens.

Or it could be a matter of just not being the right fit for each other. Maybe your agent only represents kid lit and you want to move into adult. Or you really want to start writing romance, but they don’t represent romance.

It could be a matter of my agents not communicating with me. Or I feel like they’re no longer focused on me and my career, and I feel like I’m not getting the attention that I really need and want out of an agent.

Again, there’s so many reasons, but it does happen. It’s not the end of the world, it’s just a little blip, another blip in your journey.

By and large, the friends I have who have left an agent, or whose agent has left their career or whatever, then when they find someone new, more often than not, they end up feeling like, you know what? This was the right thing.

I really took my time, I found someone new who is a great fit for me, who is excited about my career and my upcoming projects, and who is really working it and making things happen, and making book deals happen.

So I know it’s really hard in that moment because you can feel like I worked so hard to get this agent, why would I ever leave them and go back to querying?

So really try to take a big picture look and think, well, I might be going through a bad spot now, but what is the potential payoff in the end? What do I stand to succeed and to gain in doing this? So it’s a tough decision. It’s not a fun part of the career, but it is a reality for a lot of us.

Joanna: If you want a long-term career, you’re the one who is in charge.

So you just make some more choices and carry on. We don’t let that end our careers.

Marissa: Absolutely, and you’re always going to be your best advocate.

We think of our agents as our advocates, and we think of our editors as our advocates. They absolutely are, but ultimately, no one is paying as much attention to your career as you are. So we really have to speak up for ourselves, first and foremost.

Joanna: We’re almost out of time, but I have to ask you about book marketing because it is a part of every author’s life, and again, something where happiness and joy might not be such a big part. So how can we make marketing more fun?

What do you enjoy most about book marketing?

Marissa: Oh, my gosh. If you figure it out, you let me know.

Joanna: Well, I like podcasting. So, there you go.

Marissa: I also really enjoyed podcasting, although I did just retire my podcast because, again, too many things, too many spinning plates, and you have to make some tough choices sometimes.

For me, you know, find the things that you do enjoy. I learned early on, I don’t like Facebook, and I don’t like Twitter/X. It was difficult pulling back from those because I had a fair amount of followers, but when I did, it was clearly the right decision. I wish I’d done that a long time ago.

Then it allowed me to focus my energy and my attention on Instagram, which is the platform that I just naturally gravitate toward best. I just enjoy it the most.

Pick and choose the things that you do get some enjoyment out of, and then set boundaries around it.

We were talking about the TikTokers who feel like they have to make multiple videos every day. Figure out what—again, back to limitations— what is your capacity?

Have a plan in place and say, okay, I’m going to post three times a week, or five times a week. Or maybe I’m going do Fan Art Fridays, and I’m going do New Book Tuesdays or whatever it is, and then maybe I’ll have one fun family post, or one fun “this is a quirky thing about me” post every week.

So you can kind of have a plan and break it down so that you’re not every morning looking at your phone thinking, “Oh, I have to post on Instagram again,” or, “I have to do a TikTok video. Now, what am I going to talk about?”

I also think it’s helpful to maybe once a month, or maybe at the start of a big promo season, spend some time doing your big brainstorming and kind of like batch.

I like batching things, like the things on my to-do list.

So I’ll spend a day brainstorming what I want to post, and then I’ll spend a few hours taking the necessary photos and trying to put together the captions or trying to put together the graphics or whatever. Then that’s done, and I don’t have to worry about that for a couple of weeks, maybe a month, if you’re really productive.

So it’s a really nice, efficient way to tackle that and then be able to move back to writing, which is, for most of us, the thing that we would rather be doing.

Joanna: Absolutely. Now, the book is The Happy Writer.

Where can people find you and all your books online?

Marissa: Thank you so much. I can be found on Instagram at MarissaMeyerAuthor, or on my website at MarissaMeyer.com. Books are available pretty much wherever you like to get your books.

Joanna: Brilliant. Well, thanks so much for your time, Marissa. That was great.

Marissa: My pleasure. Thanks so much for having me.

The post The Happy Writer With Marissa Meyer first appeared on The Creative Penn.

Go to Source

Author: Joanna Penn

Artificial intelligence is changing the way we do just about everything these days, and the impact of AI on fiction writing is no exception. As a writer who cherishes the creative process, I have spent the last few years grappling with both the possibilities and pitfalls this new technology brings. On the one hand, AI offers tools that can make our lives easier—such as helping with research, marketing, and even ideation. On the other hand, it raises questions about originality, authenticity, and the integrity of human storytelling.

Artificial intelligence is changing the way we do just about everything these days, and the impact of AI on fiction writing is no exception. As a writer who cherishes the creative process, I have spent the last few years grappling with both the possibilities and pitfalls this new technology brings. On the one hand, AI offers tools that can make our lives easier—such as helping with research, marketing, and even ideation. On the other hand, it raises questions about originality, authenticity, and the integrity of human storytelling.

Creative burnout can feel like a wall between you and your writing goals. Whether it’s the result of stress, distractions, or feeling creatively drained, creative fatigue and even injury is something many modern writers experience. Because writers are generally a solution-forward bunch, we often think we can ten-step our way out of the problem. However, when creativity itself is the problem, the resources to heal can often be counter-intuitive. Creative burnout recovery isn’t about forcing your way back to the page; it’s about holistically creating space in the rest of your life for your creativity to breathe and rebuild.

Creative burnout can feel like a wall between you and your writing goals. Whether it’s the result of stress, distractions, or feeling creatively drained, creative fatigue and even injury is something many modern writers experience. Because writers are generally a solution-forward bunch, we often think we can ten-step our way out of the problem. However, when creativity itself is the problem, the resources to heal can often be counter-intuitive. Creative burnout recovery isn’t about forcing your way back to the page; it’s about holistically creating space in the rest of your life for your creativity to breathe and rebuild.

Recent Comments